Every winter, the serene Northwoods region of Wisconsin hosts a legendary display of endurance and tradition. Skis glide atop fresh corduroy and perfectly laid tracks that cut through the forest dense with pine, oak, maple, birch and poplar. Skiers push forward like locomotives, puffing clouds of warm breath into the crisp air. After more than 1,370 meters of climbing over a distance of 50 to 55 kilometers, the Hayward water tower comes into view just beyond frozen Lake Hayward—the home stretch.

As over 8,000 skiers make their way across the windswept lake, hearts quicken at the sound of church bells convivially ringing in the distance. At last, they arrive at the International Bridge: a 24-foot-wide, 198-foot-long ski bridge temporarily constructed for this day each year, which takes athletes 16 feet up and over U.S. Highway 63 into the heart of downtown Hayward.

Participants ski down the American Birkebeiner International Bridge. (Photo Credit: American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation/James Netz)

Crews haul in 82 dump truck loads of snow to cover the two-and-a-half-block-long finish along Main Street. More than 30,000 screaming fans—a kaleidoscope of colorful spandex and puffy jackets—stand in stark contrast to the white base. They shout words of encouragement as the sound of cowbells reverberate off the buildings on either side of the roadway, urging skiers on to the finish line.

This is the American Birkebeiner—the largest cross-country ski marathon in North America and the third largest in the world. For five days in February, the Nordic skiing festival, often referred to as the “Birkie,” takes over the old logging community of Hayward, Wisconsin, population 2,300. The 50-kilometer skate (freestyle) and 55-kilometer classic races—which begin in Cable, Wisconsin, northeast of Hayward—are the main events, drawing participants from nearly every state and dozens of countries. In total, nearly 45,000 athletes and spectators attend each year for the event, now in its forty-sixth year.

“By the time you come down Main Street, your body is at its max, and you are digging for those final reserves of energy to get to the finish line,” said Kikkan Randall, a five-time competitor in the winter games and gold medalist who will be skiing the 50K event for the second time on Feb. 22, 2020. “But as exhausted as you are, to hear the noise and the encouragement, it gives you an extra gear to get to that finish line. It’s downright emotional in so many ways.”

Kikkan Randall competes in the 2019 Birkie. (Photo Credit: American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation/Lenora Ludzack)

“It’s really an electric atmosphere to encounter after skiing on your own through the woods,” added Ben Popp, executive director of the American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation (ABSF). “Best of all, citizen skiers get the same experience as the elites.”

Indeed, over the last half century, the race has transformed from a low-key endurance event characterized by Northwoods solitude into a celebration of the outdoor winter lifestyle. While this now-iconic race remains one of the toughest ski marathons (long-distance ski races) in the world, the pomp and circumstance of today’s race is a product of years of tradition.

Humble Beginnings

It all started with Tony Wise. While serving in World War II, he took note of Bavaria’s ski culture, and liking what he saw, Wise decided to bring it home with him to tiny Hayward, Wisconsin. He opened the Telemark ski area down the road near Cable in 1947, first as an alpine venue. A grand lodge opened in 1972, and upon the urging of several locals who had roots in Norway, he began to lay the groundwork for what would become a destination for Nordic skiers.

Tony Wise (center) with two skiers. (Photo Courtesy: American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation)

The first American Birkebeiner took place in 1973 and was named for the Norwegian Birkebeinerrennet ski race. Both events commemorate the thirteenth-century Birkebeiner warriors, a name they gained thanks to the protective birch bark leggings they wore. Amid civil unrest between two rival parties vying for control of Norway in 1206, the Birkebeiners came to the aid of the young Prince Haakon of Norway by carrying him to safety from Lillehammer to Trondheim on skis.

Thirty-five skiers (34 men and 1 woman) lined up at the inaugural Birkie, including 25-year-old Ernie St. Germaine. (He remains the only skier to have completed all 45 Birkies, with no plans of quitting anytime soon.) An employee at the Telemark Lodge at the time, he was urged to compete in the race by a local Norwegian, Lyman Williamson. When Williamson turned 72, his wife, Edna, forbade him from participating on account of his age. St. Germaine recalls Williamson urging him to participate, saying, “My boy, you will ski the race and represent me.”

The inaugural Birkebeiner took place in 1973 with 35 participants. (Photo Courtesy: American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation)

A week prior to race day, St. Germaine showed up at the Williamson abode, first to eat Edna’s famous pancakes and then to don Nordic skis for the first time. An experienced alpine skier, Williamson instructed St. Germaine, “Just glide, my boy!” After practicing a bit, St. Germaine shrugged and said, “I guess I’m ready.”

There was little fanfare. After winding 45 kilometers along snowmobile tracks and logging trails through the woods, the first Birkebeiner course took skiers to the downhill slope just outside the Telemark chalet, where the alpine skiers watched with great amusement. “It was quite a spectacle with these crazy [skiers on skinny skis] coming down the hill and in my case, crashing at the finish line to stop,” St. Germaine remembers.

After picking himself up, St. Germaine received a small participant medal from a finish line volunteer who patted him on the back and said, “The devil sure got into you today!”

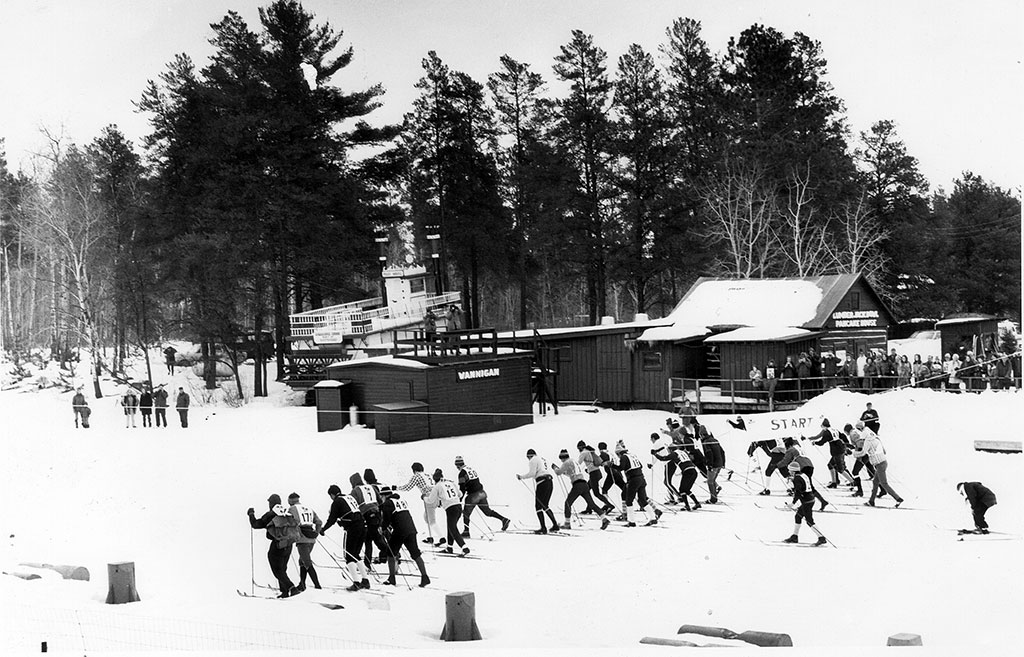

The starting line at the 1979 Birkebeiner (Photo Courtesy: American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation)

Although the race steadily attracted more skiers each year, St. Germaine and race organizers say it wasn’t until after the 1976 winter games, where American Bill Koch won a silver medal in the 30K event, that the Birkie started to become the remarkable event it is today.

“If you ask me what has kept me going, in the early days it was the fact that Tony just expected us to keep doing it to help him promote the sport. Now, I suppose it’s mostly that nobody ever taught me to quit. Every year after I cross the finish line and I’m back in the arms of family and friends who support me—they keep me going too,” said St. Germaine, who is now himself 72 years old.

Ernie St. Germaine (Photo Credit: American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation/Kelly Randolph)

The modern American Birkebeiner is part of the Worldloppet Ski Federation, which comprises 20 global ski marathons. Along with over 8,000 citizen skiers, the 2020 Birkie will host around 430 elite participants from around the world who will compete for nearly $40,000 in prize money.

In addition to the signature 50K skate and 55K classic races, the Birkie ski week now includes the 29K Kortelopet race, 15K Prince Haakon race, as well as adaptive, kids’, junior and skijor (dog-powered cross-country skiing) races. All told, more than 13,500 athletes participate in the events. A number of long-held traditions add to the charm, including pre-race spaghetti feeds, mid-race shot skis and skiers who travel the entire course in full thirteenth-century period costume to pay homage to the race’s inspiration.

Skiers portray the Birkebeiner warriors during the 2019 race.

(Photo Credit: American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation/Kelly Randolph)

This is all made possible by more than 3,000 volunteers, as well as seasonal and full-time staff who assemble packets, groom trails, offer refreshments and provide medical care, among other duties.

“I’m amazed and awestruck when I see all the volunteers out there supporting the race each year,” St. Germaine said. “When you reach the top of the bridge, you forget the months and months of training, skiing, working, all for that one moment in time as the roar of the crowd overwhelms you.”

As a result of the tricky logistics, there are few point-to-point courses like the Birkie anymore, Popp says of the unique event. “The nearly 4,800 feet of [elevation gain] and relentless winding up and down through the woods creates an event that is perceived as the ultimate challenge,” he said.

Randall, who has skied all over the world throughout her career, describes the Birkebeiner as “one of the more exciting race atmospheres” she’s experienced.

An Uncertain Future

Like so many treasured winter traditions, the American Birkebeiner faces an unpredictable future due to climate change. In 2017, after weeks of above-average temperatures and rain, race organizers canceled the event for the second time in the race’s history (the first time was in 2000); eight other years it has been shortened due to lack of snow or unseasonably warm weather that left open water on Lake Hayward. The Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts projects increases of up to 11 degrees Fahrenheit during winter by the middle of the 21st century across Wisconsin, with the most intense warming in the northwestern corner of the state where the Birkie takes place.

Organizers and skiers are racing to preserve this irreplaceable event in the face of this existential threat. In addition to being an important part of the fabric of both the Northwoods culture and cross-country ski community as a whole, silent sports (self-propelled, aerobic activities) like the Birkie generate an estimated $26 million in revenue for the local economy annually.

The 100+ kilometer American Birkebeiner Trail, where the races takes place, sees over 100,000 users per year, and in 2016, USA Today readers named it the “Best Cross-Country Ski Destination” in the country. (When the snow melts, the ABSF also maintains the trail for running and mountain biking.)

Photo Credit: American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation/James Netz

In 2018, the American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation raised $650,000 in funds to purchase snowmaking infrastructure. They currently have the ability to put down at least a 3.75-kilometer made-snow loop, with a goal of 20 kilometers, meaning they could build a looped course and potentially host a shorter event. For many reasons, in Popp’s mind, it’s far from an ideal long-term solution.

“We are conflicted about snowmaking because we want to be good stewards of the environment, and making snow consumes huge amounts of energy. We are looking at how we could offset it with a solar grid of some kind,” he said.

Like Popp, Randall believes iconic races like the Birkie offer hope for the future by leading the charge on sustainability and mitigating the effects of climate change.

The ABSF has also reduced plastic bag use in favor of reusable ones, constructed a trailhead building with a solar design to capture natural heat and light, and installed solar-powered LED trail lights among other efforts.

“We definitely need to work together as a ski community to address climate change and turn the tables back to a world with good winters,” said Randall. “If we all raise awareness and encourage action amongst our social groups and in our local governments, I think we’d all be surprised what a difference we can make.”

For now, trail conditions for the 2020 Birkie stand to be as good as they get. Skiers, some of whom will cross oceans to get the starting line, are all bound by one common purpose: To make it up and over the International Bridge and onto Main Street for their rock star moment—hopefully with the opportunity to do so for decades to come.