In 1948, the members of a then-rather exclusive club realized they had a problem. A “startling” number of people were getting injured, or even killed, doing the kind of activity the club was promoting: mountaineering. At the same time, the group knew it also had another problem: exploring the backcountry could indeed be dangerous and perhaps not everyone understood the risks; in those days, climbers didn’t use much in the way of protective gear—no sewn harnesses, no belay devices, no helmets. What to do?

The result of that soul-searching was a 20-page pamphlet that documented and analyzed the year’s mountaineering accidents published by the very group that loves to climb, the American Alpine Club (AAC), and distributed to its some 330 members. The Colorado-based group has continued this effort every year since, disseminating a glossy annual report of scores of accidents—from crevasse falls to falling rock—to its now 25,000 members. This rather morbid-sounding book has turned into one of climbing’s key safety tools.

“It’s an amazing publication,” said David Weber, a mountaineering ranger who’s rescued plenty of injured climbers at Denali National Park and reads it religiously. Reading about accidents is a good way to prevent them, he said.

The publication is also rather unique for its self-examination. Other fields, Weber said, “can be rather tight-lipped at times about mishaps, near-misses, or accidents.” Even the Federal Aviation Administration doesn’t publish an annual book of accident analyses like this; you have to search them out online, and the reports are very technical.

From 2016 Accidents cover: A Yosemite Search and Rescue team arrives just below the top of Leaning Tower to begin setting up 1,200-foot lowering systems. Photo Credit: Cheyne Lempe

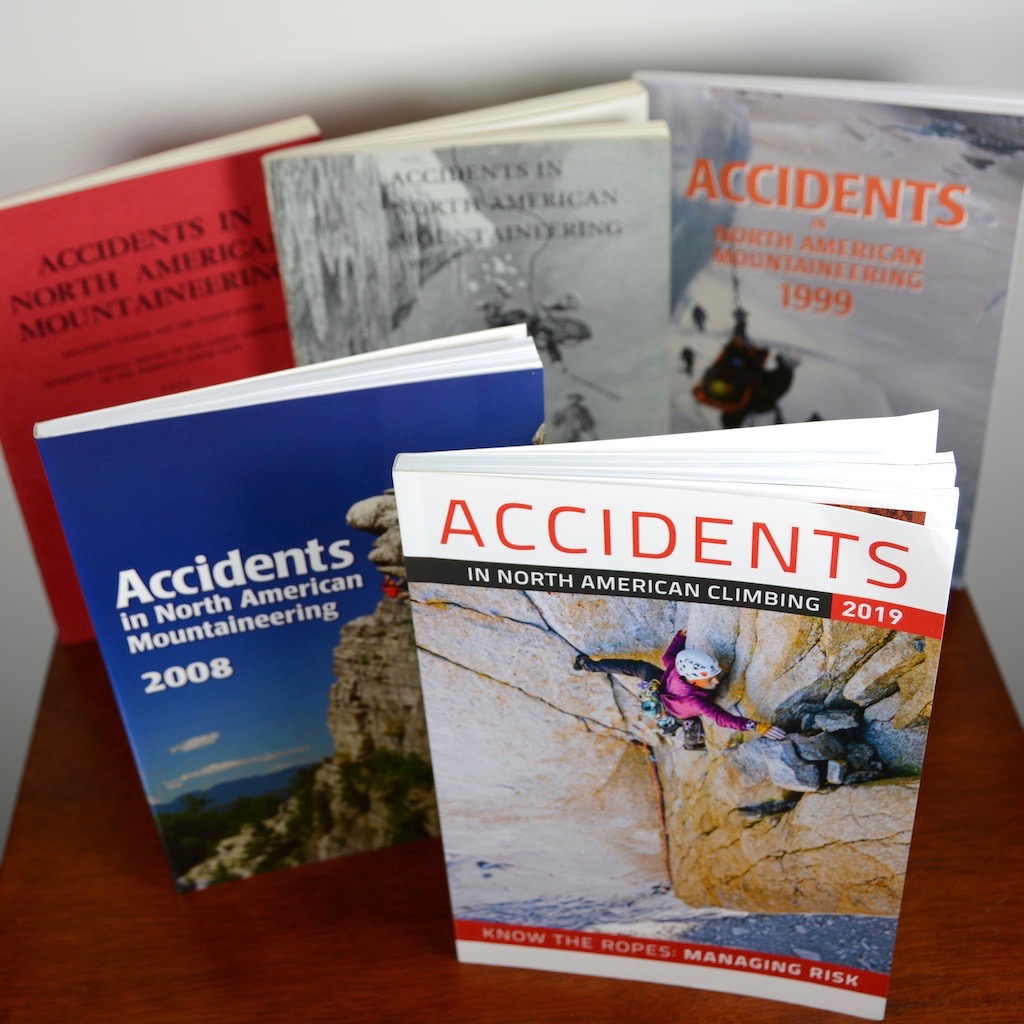

Today, Accidents in North American Climbing (ANAC), as the publication is now called, is no longer a pamphlet; it’s a glossy 120+-page book that each year recounts more than 100 accidents. That’s page after page of bad breaks, bad decisions and bad outcomes—which, admittedly, can be rather disconcerting when you first pick it up to read. Climbing legend Hans Florine recalls first hearing about the book decades ago, when he was considering joining the AAC and wondering, “Do I really want to join an organization that has accidents every year?”

What quickly becomes clear upon reading the reports is that climbing accidents don’t typically happen because of faulty gear. Nor is mother nature usually to blame. Instead, in the vast majority of cases, it’s us. “This stuff happens because we’re humans,” Weber said, “and humans make mistakes.”

The first pamphlet was published “with no intent to criticize … but rather to learn why these accidents occurred and to emphasize the lessons to be learned.”

But there’s something else about these stories that is truly remarkable. Some of the best analysis comes from injured climbers who willingly come forward to admit their own mistakes to their peers. To wit:

“….lack of due diligence was the cause of my accident…”

“I ignored some obvious warning signs”

“My mistake was …..”

As John “Jed” Williamson, the book’s volunteer editor for 40 years, says, “Climbers are surprisingly willing to tell on themselves.”

Even some of the world’s top climbers. Free soloist Alex Honnold, for example, shared the story of his vertebrae-crushing error in 2016 : he didn’t double-check the rope length before climbing and accidentally got lowered off the end of it.

It was Florine’s turn in 2018 when he suffered a fall from the Nose of Yosemite’s El Capitan that was painful and debilitating, with the added bonus of being potentially embarrassing. Here’s a guy who’s made more ascents of El Cap than anyone else, yet he had to be plucked off that granite monolith by helicopter. He could have declined to talk about what happened. He could have glossed over details. He could have blamed everything on factors beyond his control, trying to save face.

From 2019 Accidents: Yosemite rangers Brandon Latham (left) and Philip Johnson, having lowered from the top of El Capitan, arrive at Gray Ledges to retrieve Hans Florine (right). Photo Credit: Hans Florine

Instead, Florine didn’t hesitate to fess up because he knew reading about his mishap might help other climbers. In the report, it’s clear he didn’t place his protective gear properly: A nut came out when he put his weight on it to test it. That problem would have been relatively minor if he hadn’t made another mistake: He didn’t adjust his rope properly, so what could have been a shorter fall turned into a 16-foot fall onto a ledge. And earlier in the day, he and his partner had dropped a sling of gear, which may have offered more secure protection than the nut.

The cause of his broken bones, he told Uncommon Path, was “certainly user error.”

When have you heard an expert in any other field admit fault in such a clear way? Uh, never?

Yet you’ll see climbers do this all the time, both for ANAC and in other online forums. It’s a through line that stretches all the way back to the AAC’s 1948 decision that a concerted program of education was the best way to address the rising number of climbing accidents. “Only through the cooperation of all who love the mountains can ignorance be replaced by experience, sound discretion and mature judgment,” the group wrote. Their first pamphlet was published “with no intent to criticize … but rather to learn why these accidents occurred and to emphasize the lessons to be learned.”

The first pamphlet published in 1948. Photo credit: AAC Library.

It’s been an invaluable tool for the Mazamas, an Oregon-based climbing and outdoor education organization that trains more than 500 climbers each year and leads alpine climbs that serve some 1,500 people annually, said Sarah Bradham, the group’s operations director. “The beauty of it, and the reason it’s been around for long, is that it started long before our blame-and-shame culture,” she said. Instead, it set the standard for a culture of openness that characterizes the climbing community. “That’s the only way we’re going to learn,” she noted.

In the early years, some of the analysis was rather thin. Of a 1948 fatality in the South Cascades, the authors wrote, “here was a lone climber of (apparently) little experience—not enough, anyhow, to know how to make use of instructions.” They also featured reports on injuries that were more about hiking than they were about mountaineering or climbing, which wouldn’t be included today. But over time, the AAC developed a formula: Recount the incident in plain language, then add analysis to identify each misstep. Statistical information, such as the number of accidents by location or cause, is tucked in the back. There are also features on topics that benefit from deep dives, whether it’s how to speak up when your gut says something’s unsafe, the perils of cooking in a tent, or the history of accidents in a particular location.

National park rangers know how valuable this information is. They keep copies on the shelves at ranger stations, so would-be adventurers can learn about common pitfalls before embarking on their journey. All AAC members can get a free copy of the book, and non-members can buy a hard copy or a Kindle version. Rescue groups read it religiously.

But no one has done more to shape this accident prevention work than Williamson, who’s worked in a variety of outdoors-related positions and was the president of Sterling College in Vermont, which focuses on ecology and outdoor education. When he began editing the books in 1974, he received accident reports via snail mail; he phoned climbers personally to ask them to tell their story; he composed analyses and tabulated statistical data on a typewriter.

“One of the things I was committed to was never to be the blamer,” he said. “Because the whole point was education. How can we present the analysis in a way that will help people learn something?”

He continued the work, strictly volunteer, until 2014. “It was my contribution to the mountaineering community,” he said.

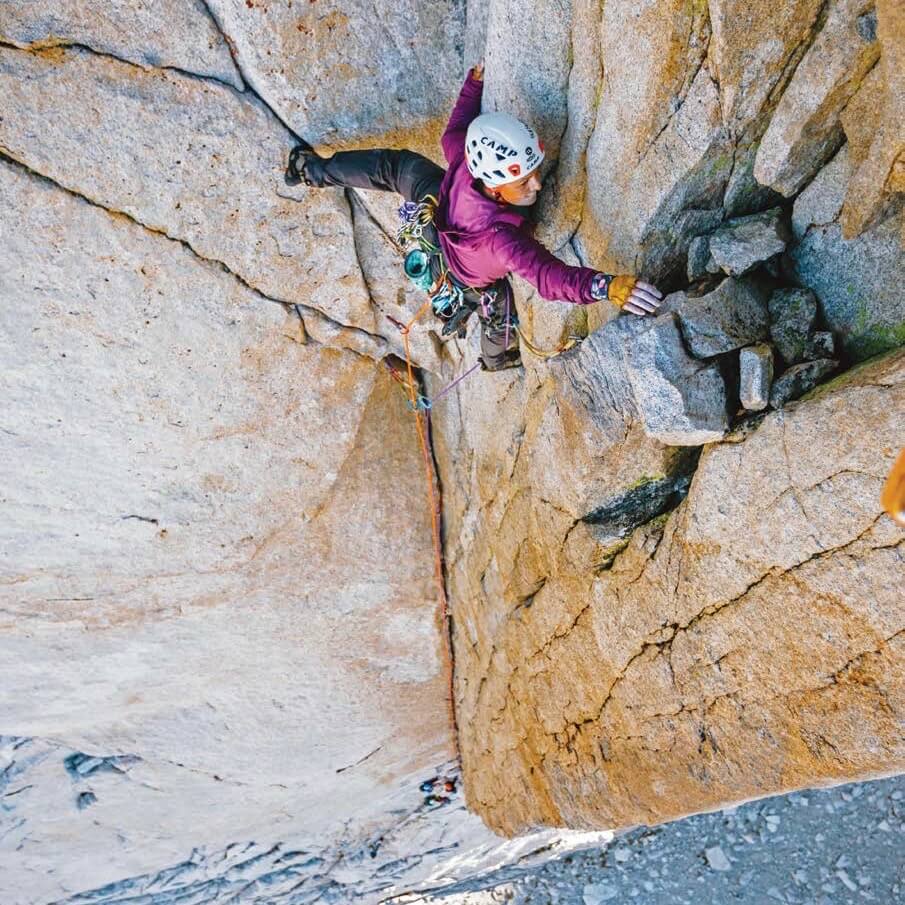

From 2019 Accidents cover: Julia Virat on the Red Dihedral (5.10), The Incredible Hulk, Sierra Nevada, California. Photo Credit: Calder Davey

Over the years, as the same kinds of accidents were documented repeatedly, climbing has changed. New kinds of belay devices were invented to mitigate common (and dangerous) errors, like accidentally releasing the strand of rope used to stop a fall. Carabiners were improved with the invention of bent gates to make clipping easier. New materials were developed for slings, such as the fiber, Dyneema, which is both strong and lightweight. Today, there are more incidents reported than in 1948—for example, 11 fatalities compared to 17 in 2018—but there are hundreds of thousands more climbers. Williams believes that safety has improved exponentially thanks to a focus on education by climbing groups nationwide.

In 2014, Dougald MacDonald took the reins as the book’s editor. It’s now a part-time paying gig, though it still relies on about 17 volunteers across the country for editing, proofreading and on-the-ground intel. They send in reports, as do park rangers, rescue organizations, groups like NOLS and state parks workers. Many accident victims submit reports themselves.

With the growth of the AAC, the educational effort has gone well beyond an annual publication. In 2013, the AAC added a searchable online component. The AAC has also expanded upon the books’ contents with instructional videos, downloadable pdfs, and a popular podcast called the Sharp End.

“I would read the books religiously,” recalled the host, climber Ashley Saupe, “and I thought, somebody should make this into a podcast. Then I thought, why not me?” In each episode, an accident victim, witness, or rescuer shares their story. This first-person storytelling is equal parts intimate, gripping and revealing.

Past issues of “Accidents in North American Climbing.” Photo credit: AAC Library

Weber, the climbing ranger, says these other educational tools are even more important than ever because so many people are taking up climbing. There are around 600 indoor climbing gyms in the U.S. now (compared to zero in 1948), and that’s where the majority of people first learn. What many newcomers might not realize is that climbing in a gym is vastly different from climbing outdoors.

“In the outdoor industry, the pictures and images are based on a really happy outdoor experience,” he said. “That’s the majority of what happens, but there’s also this other side, where people get sick, hurt or stranded.”

In that light, learning to understand those risks by reading about mistakes of the past—other people’s mistakes of the past—seems less like morbid curiosity and more like smart preparation.

Seven decades later, as the number of climbers continues to grow and with so many people exploring the outdoors, safety is even more important. There are plenty of safety tools you can buy, but there really is no substitute for the kind of tools provided through education—the tools you have in your own head.

“If the effort put forth now can save but one life or limb,” the AAC members wrote in 1948, “that effort will, most assuredly, have been well spent.”