SAR, Drugs, and Rock N’ Roll: Former Yosemite Ranger and Search and Rescue Officer reflects on rescues and adventures during Yosemite’s Golden Age

Butch Farabee, an Indiana native, had an expansive, 34-year National Park Service career, during which he served as a ranger and eventually rose to the rank of superintendent. Perhaps most impressively, he was the agency’s first emergency services coordinator, conducting more than 900 rescues, 800 of which were in Yosemite National Park in the rowdy and colorful 1970s.

In fact, Butch donned his badge during the height of Yosemite’s wild “Stonemaster” era of rock climbing, when climbing’s wiliest legends—from Jim Bridwell to John Long—were putting up bold first ascents, hiding out in Camp 4 and playing baseball with the rangers, who were both their friends and foils.

The climber’s side of the stories are well known (see Valley Uprising trailer below), but what was it like from a ranger’s perspective? Butch, now retired in living in Tucson, Arizona, tells us in his matter-of-fact style that Yosemite’s rock n’ roll days were crazy and contentious, but ultimately, climbers and rangers were united in their passion for the park that brought them together.

What are your most vivid memories of 1970s-era Yosemite?

There were some really colorful, daring and interesting climbers. Warren Harding, Jim Bridwell, Chuck Pratt. There were a bunch of these guys that were just, well, colorful. You have to admit, there were a lot of drugs going around Yosemite. There was a lot of climbing going on where mostly the young men were stoned. A lot of climbers you might look up to now were probably stoned—and then got busted by my peers!

One of the craziest stories from that time has to be the marijuana-filled plane that crashed in an alpine lake, and climbers sort of, uh, took the lead on rescuing most of the cargo. What was your role in that incident?

The plane crashed on December 9, 1976 but was not discovered until January 25, 1977 by some hikers or cross-country skiers. They reported it several days later after hiking out from the remote spot. That day several of us dove on the plane, now covered by 16 inches of ice. Much of the marijuana had floated to the surface and ultimately in two days of actual diving, as well as looking on the surface, the NPS removed about half of the estimated three tons of marijuana. We were also looking for the bodies. The weather and Mother Nature came back and we left the site alone. About six weeks later we learned that the lake, Lower Merced Pass Lake, was being visited. We then went back in and scattered those who were there, mostly climbers.

From this point until we located the bodies, we removed a few more bags of marijuana. On June 16, I was one of three rangers at the wreck site in hopes the bodies would eventually be discovered. There was a small mom-and-pop salvage group there removing metal, tires and so forth. Finally, the cockpit was exposed, and one pilot floated free and to the surface. We recovered that body. Then another diver and I went down and removed the second pilot, still strapped to the pilot chair, and brought him to shore. We now had both bodies. So, I was at both the beginning and the end of the incident.

Butch sits on a garbage bag of marijuana at Lower Merced Lake AKA “Dope Lake” | Photo: Courtesy Butch Farabee

What was the relationship like between the climbers and the rangers?

Yosemite Valley is a pretty small community. We weren’t all hardasses or bad guys. When we were off duty, we’d be with the climbers, who would take us under their wings and take us climbing up a wall. The following day, though, we might be chasing them back down the wall because they had LSD. One time, I worked with Jim Bridwell on a rescue, then the next day I had to kick him out of Camp 4 for doing a 5.7 pitch—unroped and stoned.

There’s some truth to the climbers versus rangers sentiment—there were definitely some personality clashes—but the climbers were pretty good guys overall. We ended up liking most of them quite a bit and admiring them. We’d go climbing with them as much as we could. They’d help the rangers on rescues, and some of them even became rangers.

We used to have baseball games with the climbers, too. The rangers were pretty athletic, but the climbers were in another league–though they weren’t necessarily better ball players. It was fun, a friendly competition. We did that for years.

So, in a way, YOSAR’s relationship with these guys kind of helped the sport gain some legitimacy, right?

Climbing was in its infancy, people were still doing lots of first ascents. A climbing bum would go into the park and stay for a whole summer. We had to start relying on climbers to help get other climbers out of some of the tough spots that they had gotten themselves into—rangers didn’t have the skill to do the big stuff. Over time, we started using them and the mountaineering school and Wayne Merry (part of The Nose’s first ascent), and we had a good relationship, so, between the school and the fact that there were all these hard core guys over in Camp 4, whenever we needed some extra manpower or expertise that we didn’t have, we’d use the climbers.

What did climbers do that ticked rangers off most?

There’d be a number of rescues I can recall where they’d be on the face of El Cap, they’d drop acid, and they’d be freaking out. We’d be talking them down through loud speakers. We’d have to help them out because they were so stoned. Jim Bridwell comes to mind.

There was this really big contingent of hippies. They dominated the scene even more than the climbers did, but the problem was, they all looked alike. Dirty. Long hair. You couldn’t tell hippy from climber. They’d be scarfing down at the lodge. They’d be sitting in the cafeteria, someone would get up, there’d be a half eaten sandwich, and they’d rush over to finish the food off.

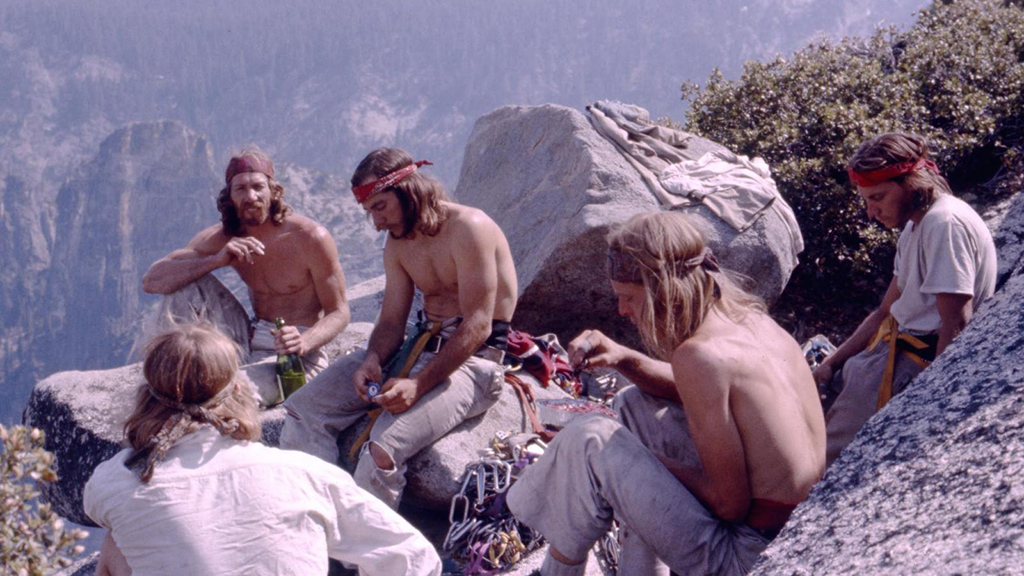

Jim Bridwell (upper left) and company | Photo by Werner Braun, Courtesy Sender Films

What personalities really stand out in your memory?

Bridwell was in many ways the king of the hill. Good looking, long hair, impeccably muscled and chiseled. We used him a fair number of times for rescues. Jim was the king, and the other guys were his court. Those Stonemasters, those guys were driven. They would party hard and they would climb hard.

What changes did you see in Yosemite since you started working there?

I was there during that very special hippie era. It was a pretty tumultuous time, a revolutionary time for the country and the park. You started to see a lot of younger people coming to the park, which was a great thing.

What was the most enjoyable part of your work?

I enjoyed the totality of the job. It wasn’t just SAR, or law enforcement, or EMS. You went to bed not knowing what was going to happen the next day. I remember one day waking up at 9 a.m. after three hours of sleep, and having to change into my wetsuit for a rescue. Then, I had to put on my climbing gear for another rescue, and next, I’m asked to go undercover to help with an arrest on a drug deal by the DEA that was in the Valley at the time. I got carried away with all the activity and the adrenaline.

What was the hardest part of working search and rescue in the Valley?

It’s the little kid who drowns in the river. The young mother who’s broken her back. The heartache of looking for somebody and never finding them.

How do you deal with that? How did you, and the other SAR officers process those events, mentally or emotionally?

I don’t know that I ever did. I don’t drink or party, some of my friends did—It was the 70’s. There’s a lot of psychological and emotional impact, baggage I guess, that we carry around. All of it takes its toll on you. It has to have some sort of impact on you. It definitely affected my marriage. It was tough.

What were the most common mistakes that got people in trouble in the Valley?

People don’t pay attention to the weather. People don’t take enough water. People don’t have the right footwear. Particularly common were people around the edge of the water not realizing how slippery the rocks are.

Was there anywhere you liked to go in the Valley to hang out, and relax?

I didn’t go to Yosemite to relax. I’d go out of the park to get away from the radio and the demands.

Do you miss it?

Well, I spent almost 40 years with the National Park Service, retiring as the superintendent. I don’t miss the bureaucratic baloney. I do miss the people, though. I still love the mission, and I adore the people.