Disclaimer: This article is written from one REI Co-op Member’s perspective and is intended to provide general knowledge; it should not be used to replace medical care or diagnosis. Consult a doctor or mental health professional before setting out on a hike if you are concerned about anxiety or feel panic. Your safety is your responsibility.

Tolmie Peak Lookout is nestled in the northwest corner of Mount Rainier National Park. On a clear day, those who hike roughly four miles to the lookout are rewarded with picture-perfect views, face-to-face with greatness: The mountain stands so close, it’s as if you could reach out and touch it. (Don’t try, though. It’s steep up there.) Glacial Lake Eunice, found along the way, makes a spectacular resting point or even a destination on its own, as people swim in its vibrant blue waters during warmer months. The hike has something for everyone, from strenuous challenges to moderate strolls.

My husband, Jon, and I had driven here countless times. We even brought our daughter here for one of our first family outings when she was just a few weeks old. But I’d never been brave enough to trek to the old fire lookout, perched at nearly 6,000 feet.

The reason? I have anxiety.

I want to be adventurous, but racing thoughts intrude. Each mile I venture deeper into the woods, my excitement is matched by dread. How can places that bring me such peace also induce such fear? I’ve often wondered.

So it was with Tolmie Peak. My spinning head always found a way to convince me that climbing to the lookout was too far, too high, too risky.

Now that I’m in my early thirties, I’ve wanted to shake off these heavy feelings that prevent me from fully enjoying what I love. I also want my daughter to grow up fearless in the outdoors. It was time to look Tolmie Peak square in the switchbacks and say, “I’m gonna hike you.”

First, though, I turned to Yasith Yasanayake for professional advice. Yasanayake, an REI Experiences guide, has led REI Co-op members on dozens of hikes throughout the wilderness of the Northeast. Their first suggestion for battling anxiety outside: Don’t go alone.

“There are many variables that can lead someone to feel like they’re in panic mode, especially in an unfamiliar environment,” Yasanayake says. “It’s best to have people you trust nearby to help you work through those emotions when they come up.”

If you struggle with anxiety, it’s important to recognize how you feel before, during and even after a hike, Yasanayake says. Occasional anxiety is a normal part of life, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, but for people with an anxiety disorder, the feeling doesn’t go away easily; symptoms can interfere with daily activities. There are several types of anxiety disorders. For example, people living with generalized anxiety disorder have difficulty controlling feelings of worry, and restlessness, or the feeling of being “on edge.” People with panic disorder, meanwhile, can experience sudden periods of intense fear, discomfort or a sense of losing control even when there is no clear danger. (This is also known as a panic attack.)

My anxiety presents differently depending on the situation. Yasanayake suggested that thoughtfully processing each part of the hike as it was underway could help me learn how to control my feelings. Here’s how that looked in practice for me.

Preparation and Packing

My first step was securing a hiking buddy. I asked Eva Seelye, an adventure photographer and my longtime friend, to help me navigate to Tolmie Peak. We set a date for my first-ever sunset hike, because I knew it would put me outside of my comfort zone. Hiking after dark is something I’d never have agreed to before, let alone suggested. There were too many unknowns, like the possibility of getting lost, injured or running into a wild animal. But with proper preparation and a knowledgeable guide at my side, the idea seemed a lot less scary.

As I loaded my car, I kept another of Yasanayake’s tips in mind: Adhere to the Ten Essentials as a fail-safe packing guide. I tossed these must-haves in my trail pack:

- Water (ideally a half liter of water per hour hiking)

- High-protein snacks

- Extra warm socks

- Waterproof hiking boots

- A hat

- A first-aid kit

- Extra clothing layers

- A light source

- Water-resistant sunscreen

- A satellite communicator

- Pepper or bear spray for self-defense

Before leaving I also did some unpacking—that is, processing the anxious feelings I knew I’d encounter during the hike. I asked for advice from my therapist, Katie Ladenburg, LCSW, who has nearly a decade of experience helping people who live with severe anxiety. She first suggested that I consider all possible coping strategies for my mental and physical “toolkit.”

“When planning for something that makes you anxious, it’s good to explore the concept of being present in your daily life and practice it before you go out and do that thing, so you have a handle on how to use that as your first go-to tool,” she explained. She suggests having a variety of tools at-hand, including prescribed medication when appropriate. “Don’t forget,” she added, “the most powerful tool is communicating to other people about where you’re going and when you’ll be back.”

Check, check and check. I shared my destination with my husband. I double-checked my pack and car supplies and tucked away my medication. (Which I take as needed when panic brews.) Before heading out the door, I grabbed one last item: a journal to write my thoughts.

“Taking a moment to process on paper why you’re doing this, while acknowledging the risks and rewards, can help contain the fear,” Ladenburg told me. “It helps you lean into doing the things you love even when they scare you, so you’re not a prisoner to that fear. That’s how you build confidence—doing something hard and getting through it. Writing your feelings down also gives you something to look back on later, to reflect on the experience.”

Managing Anxiety on the Trail

On a cloudy September afternoon, I met Seelye just outside the national park entrance. She’d done a photoshoot earlier that day, yet somehow still had energy. Her energy, and her cool, calm and collected mentality, would get me through the hike, with its 1,100-foot elevation gain. We started around 4pm.

4:47pm

We made good time on the first mile, taking a water break after about an hour. I jotted down my first journal entry: Feeling excited, sweaty and slightly out of breath as we get higher. My lungs were already feeling it. Then I remembered something else Yasanayake said: Communicate what you’re feeling as it’s happening.

“Allowing yourself to voice, ‘I’m kinda freaking out right now,’ or anything else that comes up is critical,” they explained. “As a guide, it’s on me to facilitate that kind of environment during an REI experience, but also on participants to speak up when it’s happening and not be afraid to do so.”

I told Seelye the elevation was starting to get to me, and I needed more time. We took a minute to soak in the forest’s silence, gazing at the wall of dense, gray mist we’d be meandering through for the next few hours.

5:56pm

An hour later, we reached the crystal-clear water and breathtaking scenery of Eunice Lake. I looked to the opposite shoreline, the glasslike water reflecting the moody sky above.

“There it is! We’re so close!” Seelye said as she pointed toward the fire lookout about a mile away. But to me, it might as well have been sitting atop Mount Everest. Familiar, anxious thoughts started to creep in. I doubted whether I could do this, beating myself up that I struggled with a distance that seemed easy to my friend. I even tried to cut the trip short, saying, “Let’s just eat here. It’s too cloudy to see anything, anyway.”

Thankfully, Seelye wouldn’t let me quit. She agreed that the tower seemed high from where we were standing, but also that it wasn’t as far as it looked. She’d validated my feelings—but she also didn’t let me back out so easily. Her encouragement recalled another tip from Ladenburg: Remind yourself you’re prepared. “Surrender to that reminder when you’re not feeling confident, and try to put some trust in yourself,” she had said. “Say, ‘I’m doing this and I’m a little scared, but it’s more than likely going to be fine.’ Thinking about the statistics of how many other people have done something similar can help in those times too.’”

6:36pm

Feeling intimidated and uneasy, I journaled. The sun will be setting soon. To keep such intrusive thoughts at bay as we hiked the final stretch, I talked Seelye’s ear off and kept an eye on the clouds veiling the mountain.

Suddenly, a small, snowcapped ridge peeked out in front of us. I felt my anxiety start fading. Is this really happening? I thought. Am I about to reach my first summit? We picked up the pace, buzzing with excitement that we might be minutes away from the view of a lifetime.

7:01pm

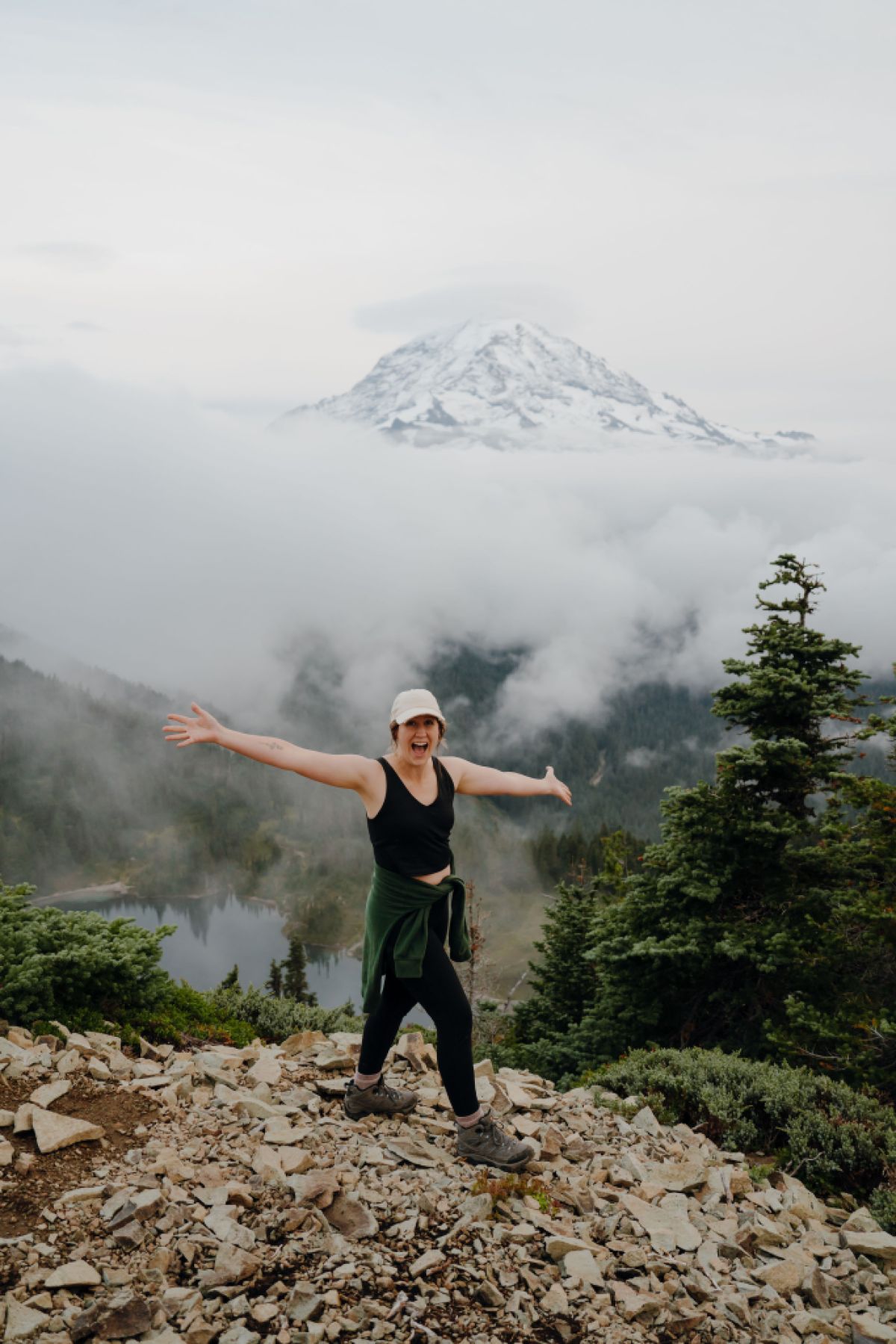

With a heart rate as elevated as the ground beneath us, we turned the last corner—and, miraculously, the clouds were rapidly lifting. There she was, Mount Rainier (Tahoma in Puyallup) in all her glory.

The mountain and surrounding peaks seemed to drift on a magic carpet of clouds—a phenomenon called a temperature inversion. I’d never been in a spot to see one before. And I definitely wouldn’t have experienced it if I’d let my anxiety win. As I stood in awe at 5,900 feet elevation, I felt on top of the world in every way.

I penned another journal entry to commemorate the moment: “Feeling proud, at peace, happy and … still scared for the sun to go down.”

7:40pm

Though I wanted to live on that mountaintop forever, the longer we waited to descend, the darker it would be. As Seelye helped me get my headlamp on straight, I blurted out, “This is the part I’m most afraid of!” As if on cue, the clouds rolled in, and raindrops hit the back of my neck. I scoured my brain for another expert tip that would calm me during the dark descent. The concept of “grounding” came to mind.

“Grounding is anything that brings you back to the here and now,” Ladenburg had told me. “This involves different forms of meditation, like yoga or breathwork—taking a minute to focus on nothing but breathing,” she said. It could be as simple as “thinking of a phrase that brings you confidence or stopping to physically touch the ground and connect with the earth.”

Posing in downward facing dog on a downhill slope didn’t seem smart, so I instead took a few deep breaths and concentrated on the phrase I’d put in the back of my mind for just this occasion: “I am prepared, and I am capable.”

Between these exercises; focusing on the dirt in front of me; and sticking close to my trusty trail companion, I made it down the steep terrain. I followed my headlamp’s shining beam for three winding miles until it met the main road, then let out a relieved sigh when I finally saw our car.

9:03pm

“We did it!” Seelye and I rejoiced as we kicked off our boots and threw our packs to the ground. “You climbed a damn mountain,” she reminded me, congratulating me on all that I’d overcome. As we pulled out of the park and onto the highway, I put one last expert suggestion into practice: Make time for self-reflection.

Reflections of a (Formerly?) Anxious Hiker

“The ‘after’ part following an anxious event is about making peace with the narrative of what happened,” Yasanayake says. “It’s acknowledging the good and the bad and being humble to the experience that life has given you, in order to learn from it. Then, it’s thinking through things like, ‘If those anxious feelings came up, why? When did it happen? Am I OK with that happening again, or are there things I can do differently next time to prevent it?’”

Nearly every REI Experiences trip Yasanayake leads includes a client who’s nervous in some way, even if not everyone chooses to voice it, the guide says. It’s perfectly normal to experience some anxiety outdoors. In fact, a little anxiety can be a good thing; it can keep you aware and observant of your surroundings. Even Seelye who makes a living doing rad things in nature, still has anxious moments here and there. “As much as I love sleeping outside, I’m always on high alert for any little sound that could mean a large animal is nearby,” she admits.

Processing my emotions during the drive home was a meaningful ending to the day. I thought about how my desire to explore is stronger than my anxiety, and how I need to remember that. I also considered how enjoying the outdoors is as hard or as easy as I make it. I won’t always feel comfortable tackling multiple miles on a hike, and I probably won’t take my daughter on a trail like this for some time. Now that I know I can reach the Tolmie Peak Lookout, though, I’ll reach farther ones, in time. That’s progress enough for me.

“It doesn’t have to be all slingin’ miles and crushin’ mountains,” Yasanayake says. “Make getting outside whatever you want it to be.”