The deaths of two beloved climbers shocked the community

Hayden was 15 when I first met him. It was 2005, and I’d just moved from Yosemite Valley to Colorado to intern at Climbing magazine. HK, as he was affectionately known, was excited to learn everything there was to know about Yosemite’s big walls.

At that time Climbing was in Carbondale (today it’s in Boulder), and Hayden’s father, Michael, was the editor-in-chief from 1974 to 1998, through what many see as the magazine’s biggest glory days. When the two of them came through the glass office doors together my first week of work, his father still had a scab on his nose, an injury he received from popping a cam hook (possibly to the face) and falling on the first Zig-Zag high on Half Dome’s Regular Northwest Face while climbing the route with his son. Though he’d climbed Half Dome, Hayden had yet to climb El Cap, but it was obvious that it was in his sights. He wanted to know everything he could about Yosemite Valley life.

At first, the three of us climbed together at Independence Pass, just up the road, in Aspen. Then just HK and I would head out to the desert to climb in the Fisher Towers in Utah and beyond. We continued climbing together for many years, the last time three years ago at the steep sport crags above Golden, Colorado, in Clear Creek Canyon. That was weeks before I moved to Vermont to work at another magazine his dad had edited for many years, Alpinist. That was the last time I saw HK.

Hayden didn’t love our first and only time in the Fishers. “Is this even rock climbing?” he said with disdain part way up a mud tower before we bailed to jam cleaner lines in the surrounding areas.

Our next objective was the fingers-to-fist Crack Wars on the Rectory in Castle Valley. I don’t remember much about what happened on the upper pitches, but I recall how quickly he ran up the first pitch, taking maybe 10 minutes. Once on the summit, we rapped off to climb the formation again, this time switching up partners after running into his high school math teacher, Sarah Kate, and her partner at the base.

The wind whipped around the route Fine Jade, slowing my progress considerably, but HK and Sarah were on top in a blink. Wind didn’t faze him. Runouts didn’t faze him. Hell, even loose rock didn’t stymie him.

We climbed El Cap together while he was still in high school. Partnered with Jonas Waterman, we journeyed up the demanding El Niño (5.13c). Over several days and nights on the wall, we showed HK the ins and outs of big walling: setting up and breaking down portaledges, hauling and lowering out massive haulbags. At the bivies, we shared summer sausage, bruise-free avocados and cheese. By day he showed us his true climbing talent: He took on great runouts up fingernail-edge face climbing with grace and poise. It remains the most difficult climb I’ve been on, but it was just the beginning for HK. The following year he linked up both El Cap and Half Dome in a day. Expeditions came shortly later.

He enchanted me with his sincerity and honesty, which seems almost old-fashioned for many of his age.

He went on to take voyages to Argentine Patagonia where he climbed Exocet on Cerro Standhardt, Huber-Schnaf linked with Spigolo dei Bimbi on Torre Egger and made a fair-means ascent of Cerro Torre’s Southeast Ridge.

On an expedition to Pakistan, he once overcame a band of choss so poor that one of his partners, professional alpinist Josh Wharton said he wouldn’t consider leading it.

“The pitch made the worst rock in the Canadian Rockies look like dream stone,” reads a story on his sponsor Black Diamond’s website. At 6,300 meters, “Hayden’s feet skated, sending off showers of kitty litter that fell for thousands of feet to the glacier below. Sometimes he’d rip off microwave-sized blocks that would bounce near his waist and explode into pieces before even making it off the traverse ledge. I looked on in terror as I slowly paid out rope through the belay device. ‘I wouldn’t question him for a second if he decided to bail,’ Josh said.”

That was on the southeast ridge of The Ogre I, otherwise known as Baintha Brakk, in Pakistan, which HK would complete with the late Kyle Dempster. It’s a climb that would win him the prestigious Piolet d’Or (Golden Ice Axe) award in 2013. He would go on to climb with other legends of the sport, including Marko Prezelj, a recipient of four Piolet d’Or awards.

In October 2015, HK completed an ascent of the east face of Cerro Kishtwar in India, via the first ascent of Light Before Wisdom. It was an achievement Dougald MacDonald, Executive Editor at the American Alpine Club, called “one of the year’s most impressive big-mountain climbs.” The 20,253-foot peak took HK and partners Urban Novak from Slovenia, Manu Pellessier from France, and Marko Prezelj from Slovenia, four days to complete.

“Hayden is almost from the generation of my son,” Marko told the Co-op Journal. “He enchanted me with his sincerity and honesty, which seems almost old-fashioned for many of his age. Besides ‘vintage’ ethical standards and scruples, we shared passion and curiosity. Hayden was [an] inspiring promoter of delicious uncertainty and unknown. Everything he was doing was underlined with certain joy and lightness that was so contagious. Climbing was just one bright part of his gifted life. Hayden was earnestly interested in many other matters that we call life. He embodied the word friend. His characteristic humble influence will be missed intensely. Respect.”

When Hayden met Inge Perkins, it was a connection for the ages.

He was Marko’s friend. He was Josh’s friend. He was his high school teacher Sarah’s friend. He was my friend. He was everyone’s friend, from his hometown chums to world-class athletes to the magazine editors at Rock and Ice and Climbing and Alpinist, though he famously turned from the limelight, eschewing social media and even magazine coverage. Photographer and occasional climbing partner, Austin Siadak, called HK’s view of social media “a poor and vapid replacement for the far more important human connections.”

When HK and Inge Perkins met, it was a connection for the ages. Inge’s friend Kelsey Sather described the final weekend she shared with Hayden and Igne on her blog. “When we had drinks… before their passing, they leaned into one another, his arm around her, and they were happy. Happy and relaxed. I remember thinking, he’s the one, and I had felt this immense joy for my friend who, in many ways, was like a little sister.”

Kelsey relayed another touching anecdote about Inge’s rich, mature character, “[At age 15], she already had a savings account and woke up at 6 a.m. everyday… Inge was more responsible than [my friend and I] combined, though half our age. Her array of friends spanned across the states and decades, with the average age being, I’d guess, 35.”

Among Inge’s many accomplishments: a solo backcountry outing of the Cirque Traverse (in 17.25 hours), solo marathon-length runs and redpointing several 5.14 routes. She was also an award-winning boulderer, deep-water solo climber and Randonee racer.

They were a bright light in our community, and we expected they’d be with us for the rest of our lives. Unfortunately, that was not the case.

After a text from a friend, I obsessively reloaded Facebook, watching the news of Hayden and Inge’s recent deaths fill my feed.

On October 7th, he and Inge were swept in an avalanche at 10,000 feet on the north couloir on Montana’s Imp Peak (11,202’) in Southwest Montana. Inge died in the accident and HK—having been unable to locate her buried body in the snow—descended alone.

Perhaps the most shocking element to emerge was that Hayden committed suicide upon returning to he and Inge’s Bozeman home, after writing a detailed letter for where to search for Inge’s body.

They were a bright light in our community, and we expected they’d be with us for the rest of our lives. Unfortunately, that was not the case.

Perkins’ beacon was turned in the off position and in her pack when her body was found. It is unclear whether Hayden was carrying a transceiver, though he did have a shovel and avalanche probe, which he left at the slide, a slab avalanche released on a 38-45 degree steep slope with a north-northeast aspect, prime avalanche terrain.

Doug Chabot, director of the Gallatin National Forest Avalanche Center, discussed the slide in this video, saying: “Nine search and rescue volunteers, including two avalanche dogs, searched the debris for the missing skier.”

Gallatin National Forest Avalanche Center posted on Monday, October 9, that Inge was found under 3 feet of wind-loaded snow.

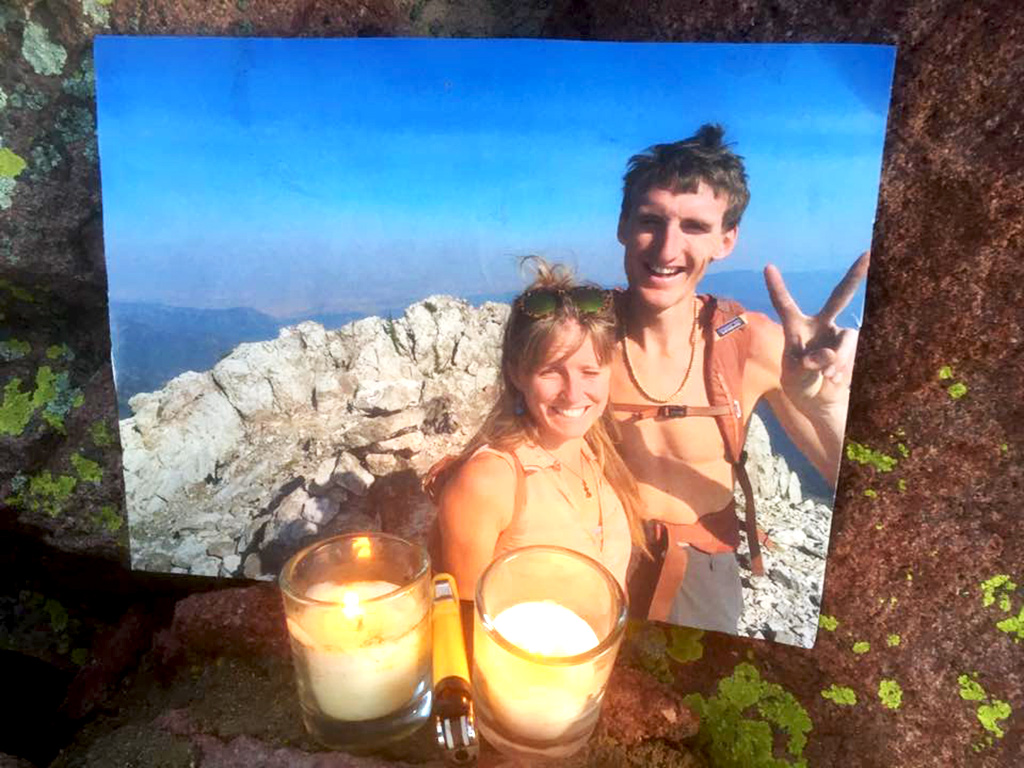

A memorial to Hayden and Inge, atop the First Flatiron in Boulder, Colorado

“Suicide is the tenth leading cause of death in the U.S.,” with 121 per day, states The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. More than 9 million people in the U.S. have suicidal thoughts each year, with 1.3 million attempting to take their lives yearly. Of those, more than 41,000 die per year, or one every 13 minutes. Men kill themselves 3.5 times as often as women, the Suicide Prevention Resource Center reports, and studies show a connection between bereaving the loss of a spouse and an increased risk of death from suicide.

“He chose to end his life. Myself and his mother Julie sorrowfully respect his decision,” his father wrote in a statement.

***

I hadn’t climbed with HK in 3 years, but we were still loosely in touch. It was only a matter of time until we met again, perhaps at his parent’s place in Carbondale, or at the crags with Josh. Sitting here outside a Boulder brewery under the blazing sun, its piercing rays partially obscured by clouds, I know I’ll never hear HK’s voice again, perhaps describing his fascination with the rap group Wu-Tang Clan. I’ll never meet Inge.

As Marko told me, “The storm of feelings is unbearable. We can share condolences, but we have to keep living.”

If you or someone you know are in need of prevention and crisis resources, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.