Summer in Alabama is notoriously hot. With average daily temperatures in the 90s and humidity reaching 85 percent, outdoor adventures can get very sweaty, very quickly. So when Kellie Clark, inaugural co-leader of the Birmingham, Alabama, community of Outdoor Afro, was considering what kind of trip to plan in July 2017, it wasn’t a hard choice.

“In the Deep South in July, you either have to be indoors or near water,” she says. She wanted to get outside, and Birmingham isn’t far from the Coosa River, the northernmost artery of Alabama’s prominent diagonal waterway. So, she got to work organizing a 7-mile kayaking trip on a cypress-lined stretch between Wetumpka and Montgomery.

***

More than 150 years earlier, plantation owner Timothy Meaher and ship captain William Foster planned a different kind of trip, according to Dreams of Africa in Alabama: smuggling 110 individuals from what is today Benin to the Mobile-Tensaw Delta, the point where Alabama’s main waterway drains into the Gulf of Mexico. The Transatlantic Slave Trade Act, which prohibited “the importation of slaves into any port or place within the jurisdiction of the United States,’’ took effect in 1808. But slavery remained legal in the United States, and the domestic slave trade flourished with the invention of the cotton gin and the high price of cotton.

Meaher made a bet that he could smuggle slaves into Alabama without repercussions from authorities. So he financed a voyage of the ship Clotilda, and hired Foster to oversee the journey. Meaher hoped to gain a cheap workforce for his own plantation, says historian Sylviane Diouf, in addition to recouping his money by selling the rest of the slaves.

***

Birmingham, which lies 250 miles northeast of the Clotilda’s destination, is today home to a growing population of tech industry professionals like Kellie Clark. A project coordinator at Innovate Birmingham, a technology economic development company, Clark describes the city as a “progressive dot in a sea of rural.” When she announced the July 2017 kayaking trip, 12 members of the 300-strong Outdoor Afro community expressed interest, but also apprehension about going into rural areas, some of which were known after the Civil War as “sundown towns” where African Americans were warned to leave before dark or else be killed.

Clark understood their anxiety. “Being in outdoor spaces, particularly in the South, when you’re Black, gets interesting,” she says.

Outdoor Afro aims to ease this concern by connecting trip participants to the Black history of the land on which trips take place. Founded in 2009, the national nonprofit hosts outings and events that reach 30,000 people annually in 28 states. Volunteer leaders coordinate urban and rural day hikes, meetups at local climbing gyms, backpacking workshops, sailing, yoga and more, drawing on the organization’s mission to connect Black individuals to nature and to Black history.

“We want people to visit their local green space and know they have a place there,” says Zoë Polk, national program director for Outdoor Afro. “One of the ways we do this is [by] telling stories about how [Black] people have always been there.”

Finding those stories, however, presents some challenges. “It’s really hard sometimes to find the history because [the stories of African Americans] weren’t worth documenting for a lot of people,” says Clark. “But you know it’s there.”

Polk encourages leaders to utilize resources like family history, stories from older members of the Outdoor Afro community, park rangers and artists.

As Clark planned the 7-mile day trip, she came across a Supreme Court case, Gray v. Crocheron 1838, and a book, Slavery in the American Mountain South, describing the experiences of enslaved ferrymen on the Coosa River. Further research left her shocked to find that Commerce Street, where slaves were sold in Montgomery, still goes by the same name.

Clark distributed as much historical information as she could to participants before the trip, which she says allowed them to take in the experience of being on the river with less anxiety. She says people show a greater sense of ownership over their outdoor experience when they know Black people have historically been in these spaces, albeit under much different circumstances.

***

With more than 77,000 miles of rivers and streams, Alabama is defined by waterways. The Coosa is the northernmost river in Alabama’s prominent diagonal waterway that runs from the Georgia state line to Mobile Bay in the Gulf of Mexico. In Montgomery, the Coosa becomes the Alabama River, and farther down, the Mobile River.

The Coosa “is a really textured, beautiful river,” says Clark. “Every couple of miles looks different.” Not only does the river feature rapids and large rock formations, but also flat sections. That texture also extends underwater, where Alabama hosts more varieties of freshwater mollusks and fish than any other state in the U.S.

The port at Montgomery on the Alabama River. (Photo Credit: Birmingham, Ala., Public Library Archives)

Fertile lowlands conducive to growing cotton flank the “wide and moody” river system, as Clark describes it. In the 18th and 19th centuries, plantations were built on the banks south of Wetumpka, with masters’ quarters set back from the river and slaves’ cabins near the shore, according to Harvey Jackson, eminent scholar in history at Jacksonville State University.

During the cotton boom in the first half of the 19th century, the waterway was Alabama’s primary transportation channel, and Ben Raines, a coastal and environmental reporter for AL.com, says the Port of Mobile saw ships coming in and out from all over the world. After the first commercially viable steamboat was built in 1807, slave traders transported hundreds of captive Africans upriver daily from Mobile to Montgomery for sale at one of the city’s slave markets.

With slaves purchased, “masters evaluated their labor,” says Jackson. Slaves with river skills were subleased as ferrymen on one of the rivers’ public ferries. Others were “rolladores” who transferred cotton bales from riverside warehouses to steamboat landings. And still others were deckhands, usually firemen, who loaded wood onto steamboats carrying cotton downriver to Mobile Bay.

***

For Clark’s kayaking group, the Coosa’s personal texture was just as important as its physical texture. The group was composed of 12 individuals, 10 women and two young boys, ranging in age from 7 to 58. There were students, nurses, professors and marathon runners. After learning the river’s history, members of the group imagined they had ancestors who either labored on a steamboat, or were transported in bondage up the river. But it can be extremely difficult to trace the genealogy of African Americans descended from slaves, so no one knew their family’s specific history with the Coosa. Clark says part of the experience was accepting they were never going to have all the puzzle pieces. “Even though it’s not ideal that those are the only pieces, [I’m] grateful to have those pieces of the puzzle to add to [my] identity,” she says.

Outdoor Afro Birmingham Leader Kellie Clark with Outdoor Afro member Trina King. (Photo Credit: Outdoor Afro)

***

Some of the only African Americans with all the puzzle pieces are the descendants of the Clotilda’s captives. In her book Dreams of Africa in Alabama, Sylviane Diouf describes a humid summer night in 1860 when, after 40 days in the hold of the ship, dozens of men, women and children were transferred to another ship in the Mobile-Tensaw Delta. This vessel, the Czar, dropped them off in the Alabama swamp, which teemed with poisonous snakes and mosquitoes, where they were stranded for 11 days.

The Clotilda’s journey is the most well-documented of any American slave ship, says Diouf, and the captain’s journal describes the entire trip from start to finish. In an effort to destroy all evidence of “the blood, the vomit, the spit, the mucus, the urine, and the feces that soiled the planks,” all telltale indicators of a slave ship according to Diouf, Foster towed the ship deep into the Alabama swamp and set it on fire.

Meaher kept 32 of the Clotilda’s captives as slaves on his own plantation, and sold the others to slave dealers and plantation owners in Mobile. Just five years later, Diouf writes, newly freed by the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, the Clotilda’s passengers bought a parcel of land north of Mobile and created Africatown, a community where they maintained their own language and customs.

***

As soon as the kayakers pushed away from the shore in Wetumpka and began paddling downstream toward Montgomery, Clark noticed her participants relaxing. Just a half-mile into the 7-mile trip, one woman leaned back in her kayak with her hands behind her head, quietly taking it all in.

Clark says oftentimes Black individuals are connected to each other and to other races through a history of pain. “Black people can forget that we’re multidimensional individuals [who are] more than our pain, trauma and the tension that exists day to day.” That’s why she hopes to foster Black joy with her Outdoor Afro trips, allowing participants to experience a range of emotions that validate the complexity of the Black experience.

Outdoor Afro Birmingham member Trina King relaxes in her kayak. (Photo Credit: Outdoor Afro)

“Historically, it has been offensive, even patronizing, for Black people to express joy,” she says. “Looking someone in the eye or paying a compliment has meant death for so many Black men, women and children. After all, the ability to experience joy would mean you are human, not chattel.” For this reason, Clark says, allowing Outdoor Afro participants to experience joy is a way to resist common narratives and stereotypes.

For Clark, practicing Black joy and self-care means engaging in outdoor activities that aren’t necessarily extreme or adrenaline-fueled, but rather a medium for meditating on the things that make us better people. “The outdoors isn’t a thing to just use,” she says. “It’s a mutual beneficial relationship.”

When one paddler started singing “A Change is Gonna Come” by Sam Cooke, it quickly spread throughout the group. The melody reverberated across the wide channel.

***

The group’s destination was just north of Montgomery, one of the most prominent slave-trading centers of the 19th century. According to the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), “between 1808 and 1860, the enslaved population of Alabama grew from less than 40,000 to more than 435,000.” Steamboats delivered captives to present-day Riverfront Park, where they were herded up Commerce Street in shackles to one of many slave pens or warehouses. Others went to slave depots, where up to 500 slaves were detained at a time and sometimes traded before being auctioned off at Court Square. In 1859, there were as many slave depots as hotels and banks in Montgomery.

***

Three miles and less than two hours downriver from the group’s launching point in Wetumpka, the Coosa splits and paddlers must make a choice. To the left, the river is calm, and to the right, a series of Class 2 and 3 rapids launches paddlers a few miles downstream, where it remains calm until the route’s terminus just north of Montgomery. Clark explained the options and encouraged each person to choose whatever they were most comfortable with.

Everyone chose to go right. Clark describes the scene with pride, noting this was the moment when she knew the trip had served its purpose. She loves the sense of adventure that a supportive group can inspire, and she says had it not been for Outdoor Afro, she’s not sure the group would have decided to take on the challenge.

Partway through the rapids, a few people pulled over onto an island for lunch. It was only noon, but already a sense of community had formed. Sandwiches in hand, they watched their fellow participants fall out of their boats after hitting the rapids sideways. The laughter was deep and joyful.

***

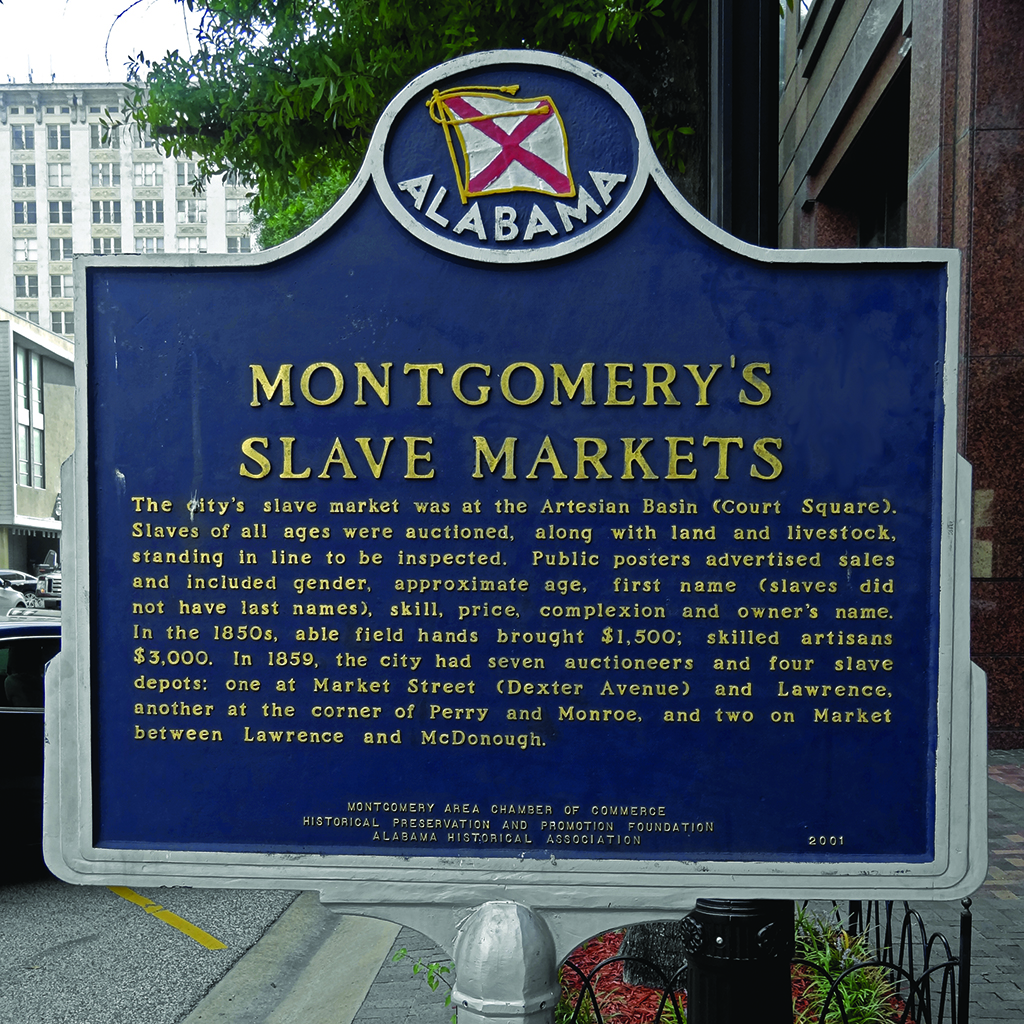

A historical marker at the corner of Commerce and Montgomery streets in Montgomery alerts passers-by to the slave markets that existed there until the end of the Civil War. It describes where slaves were auctioned (Court Square) and how much they were sold for ($1,500 for field hands and $3,000 for skilled artisans).

Photo Courtesy: Equal Justice Initiative

Polk says signs like this one are important because they document not just what happened, but where it happened. “This land was a source of trauma,” she says, “and it should also be a source of healing.”

Outdoor Afro leaders around the country are working with local, regional and national land managers to make sure this history is told. Polk says for the most part, park staff nationwide have been receptive to adding Black history to park literature, although the process can take several years.

“Erasure of Black stories was a tactic used during slavery, Jim Crow, and even now, to dehumanize Black people,” she says. To combat this, Outdoor Afro is building an online archive that will house local Black history resources for destinations around the country, in addition to planning trips like Clark’s that unearth and communicate the history of the area. In conjunction with organized efforts like these, Polk says one of the most important methods of storytelling is trip participants sharing what they learned with their communities.

For Polk, this is where healing starts: everyone, not just Black individuals, telling stories of Black triumph and joy that paint a more complete history.

***

The sound of laughter made Clark smile as she wandered off to a quiet bank to take it all in. As she gazed out at the rapids, an unsettling contradiction struck her. She imagined being in this open space with woods on either side and no gates or walls, yet still in bondage. “You’re in the outdoors, which should be freedom,” she says.

Clark felt a pang of guilt and irreverence. I’m out here laughing, eating my sandwich, and we’re singing songs, she thought. It felt wrong to be reveling in a place that had been a source of trauma for so many Black people over hundreds of years. But then she realized this was exactly the point, to take in these spaces in ways her ancestors could not, and to not just frivolously exist in outdoor spaces, but tell the stories of those who came before.

Her mind settled, and she looked across the wide river to see the joyful, wet faces of her trip participants. This was the point, she knew, these people who, “despite history, despite current climates, still choose to live and exercise Black joy and their humanity, and who choose to do that in outdoor spaces because they value the space.”

Photo Credit: Outdoor Afro

Clark is planning a camping trip for late April in the Sipsey Wilderness, a section of Bankhead National Forest two hours north of Birmingham that boasts dramatic waterfalls, sandstone cliffs and old-growth forest. On the Coosa, she learned giving people time to commune with nature and each other is more important than sticking to a rigid agenda, and she plans to honor this on the upcoming camping trip. Nationwide, dozens of Outdoor Afro trips are scheduled for the spring, and a group of 11 leaders plans to hike Mount Kilimanjaro in June to further the organization’s mission internationally.

“Our ancestors weren’t [outside] under the best circumstances, but we can be,” says Clark. “Knowing this history gives all of us more context for the present and lets us know how to interact with each other currently.” She hopes these interactions will be informed, supportive and full of revelry.

Outdoor Afro has been one of REI’s national partners since 2012.