Pete Ripmaster has been trying to play more golf lately. Eighteen holes is a far cry from the ultramarathons the Asheville-based runner is accustomed to, but he’s earned a bit of a rest. In February, the 41-year-old athlete won the Iditarod Trail Invitational (ITI), a legendary race that takes runners, bikers and cross-country skiers on a 1,000-mile journey across Alaska’s vast wilderness, from Knik to Nome. It’s the longest winter ultramarathon in the world and, according to Runner’s World, one of the toughest winter footraces on the planet, following the same route as the legendary dogsled race.

Only six runners were invited to compete this year, and only two crossed the finish line in Nome. Ripmaster, who is also known for running 50 marathons in 50 states, had attempted the race twice before but never finished. During his 2016 attempt, he fell through the ice of a river 200 miles into the backcountry and had to self-rescue, dragging himself out of the water and continuing the race for another 300 miles.

Even without dramatic setbacks, the ITI is a physical and mental challenge like no other. Racers are largely self-supported, towing all of their gear on sleds and taking responsibility for route-finding during the entire course. After winning the footrace, Ripmaster’s greatest challenge might be moving on from a goal that has consumed so much of his life for the last several years.

“I knew that the Iditarod was a huge part of my life,” says Ripmaster, who has a wife and two children. “I’d love to think that family and faith are more important, but once I finished, I realized how “all in” I was in the process of this race. It’s a good feeling to be done with something you worked on for seven years, but now what?”

This year’s race took a physical toll on Ripmaster unlike any of his previous attempts. When he started the race, he weighed 205 pounds. When he finished, he was down to 169 pounds. He completed the run in 26 days, 13 hours and 44 minutes. While the weather was relatively benign (according to Ripmaster, he enjoyed balmy minus 20 degree temps this year compared with the minus 60 degree temps during his 2016 attempt), there was much more snow to contend with on the course. Alaska had a record amount of snowfall over the winter, requiring Ripmaster to wear snowshoes for 700 miles of the 1,000-mile footrace. During all of his previous Iditarod attempts, he had used snowshoes for a total of five miles.

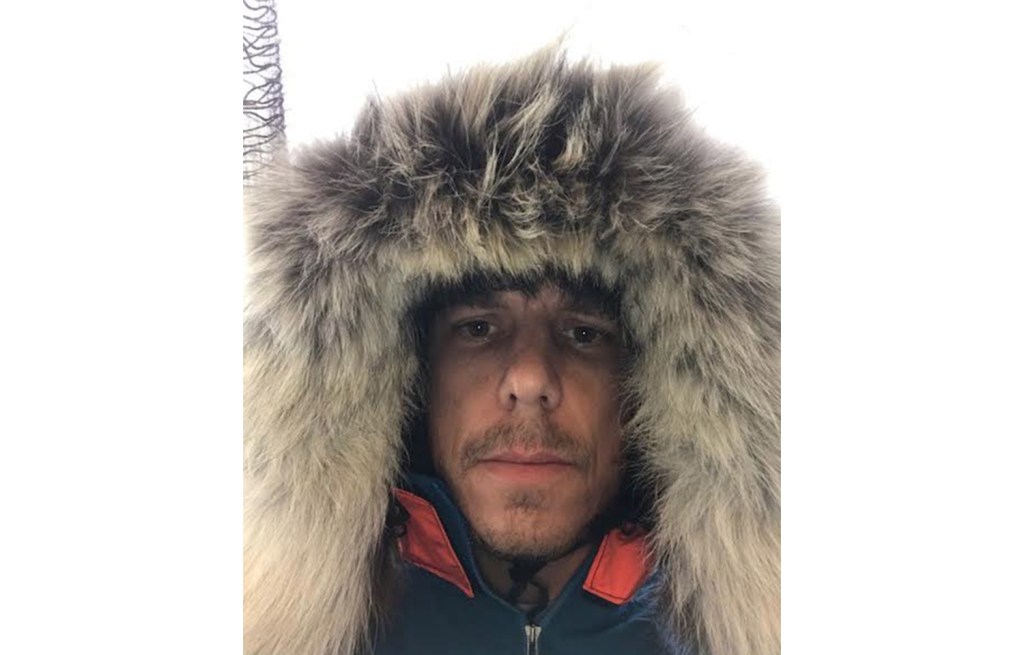

Ripmaster looking bundled up. During the ITI, temperatures can drop to as low as minus 60 degrees Fahrenheit. (Photo Credit: Pete Ripmaster)

“It was absolutely brutal, really slow going,” Ripmaster says. “But I’m super competitive so I laid it all out there and went all in. I completely depleted myself.”

In addition to the deep snow, Ripmaster contracted giardia during the last half of his race, which completely taxed his system. Roughly 800 miles into the backcountry, the runner hit a low point as he reached a shelter cabin along the route. “I was crying, didn’t have a lot of food left. I was missing my family and the giardia had started. … I was feeling bad for myself.”

At his lowest point, Ripmaster stepped out onto the deck of the shelter just as a local hunter was cruising by on his snow machine. The passerby asked if Ripmaster was OK. “We ended up talking for four hours that night,” Ripmaster says. “I was at my most vulnerable and completely opened up to him, crying the whole time. It was so therapeutic. He was full of compassion and just listened. I needed him to come along at that point. It was divine intervention.”

That chance encounter helped Ripmaster finish the Iditarod, but now the runner finds himself at the beginning of another challenge as he navigates life after completing such a lofty goal.

“The Iditarod was a defining point in my life,” Ripmaster says. “It’s been a tough reentry back into normal life. I underestimated what completing that race would do to me physically and emotionally.”

A moment of contemplation on the trail. Training for the ITI consumed Ripmaster’s efforts for the last several years. (Photo Credit: Pete Ripmaster)

Ripmaster has regained some of the weight he lost and is running slowly again, trying to rebuild strength. Recovery is a day-by-day battle that has proven difficult, but he’s hopeful for the future. He’s done with winter ultras for a while, but is planning to run the Leadville Trail 100 in August and hopes to do an intrepid adventure run in the mountains surrounding Asheville in the fall. As for epic goals that could consume his focus and energy like the Iditarod did for the better part of a decade, Ripmaster is thinking of returning to Alaska.

“Denali. At some point, I’m going to climb that mountain,” Ripmaster says. “It’s there, it’s my country. I need to climb it. I’m thinking about a dream trip, where I dog mush in, climb up to the peak and ski down. That’s the dream trip at this point. But we’ll see if I can make it happen. One thing is for certain, I’m not going to sit around drinking and watching TV.”