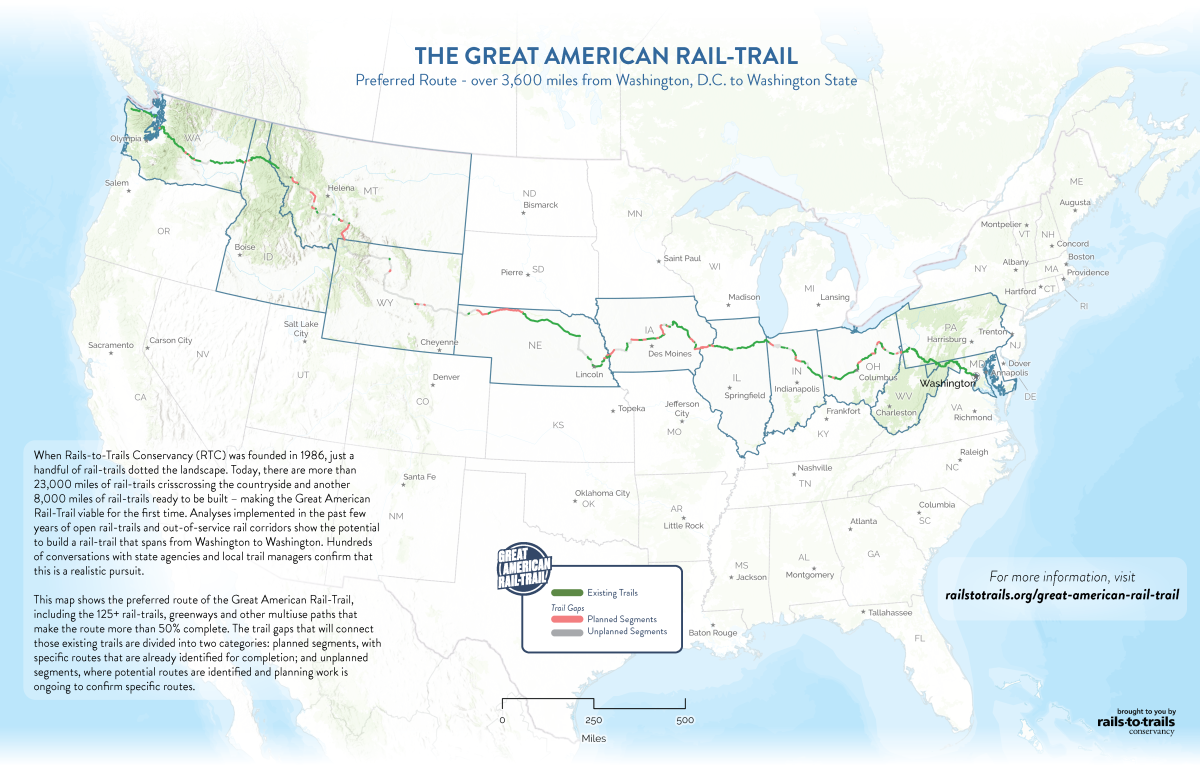

The Rails-to-Trails Conservancy released today the official route for its previously announced Great American Rail-Trail—a sprawling, multiuse trail that traces the path of converted, disused railways to connect Washington D.C. to Washington state. The 3,700-mile route (updated from a previous iteration that was 3,600 miles long) is completely separated from major roadways and includes iconic existing trails, like the Cowboy Recreation and Nature Trail in Nebraska and the Palouse to Cascades State Park Trail in Washington. Once complete, the Great American Rail-Trail will be a landmark resource for cyclists, allowing them to navigate across the country safely while staying off major roadways and on a gently graded, designated trail.

[Read our previous coverage: The Great American Rail-Trail Is On the Way]

“This isn’t just an ambitious and transformative project of a route. It’s part of a bigger movement to connect the entire nation by trail,” said Ryan Chao, Rails-to-Trails Conservancy president. He says it will be a meaningful experience for all who use the trail. “This will really unite the country.”

Photo Courtesy: Rails-to-Trails Conservancy

[View an interactive map of the route.]

The development of the Great American Rail-Trail will also make a big difference in local communities across the country.

“To me, this route is just a testament to how grand visions really do materialize,” said Donna Gaukler, the director of the parks and recreation department for Missoula, Montana, one of a myriad of big cities, small towns, and rural areas the route will service. “It’s just amazing to me what partnerships can build. This is a grand vision that might have seemed like a pipe dream, and it will ultimately materialize faster than anyone expects because of the work of partnerships.”

The Great American Rail-Trail will also travel through—in no particular order—Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Columbus, Ohio; the wide-open spaces of central Indiana, and the mountains of Wyoming. When the concept was announced in January, the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy shared 12 gateway trails that are anchor points of the route. The map revealed today is much more detailed, and the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy hopes cyclists across the country will realize how much of the trail is already open, and that the new map will encourage cyclists to start planning trips around it.

The Headwaters Trail in Montana. (Photo Credit: Scott Stark / Courtesy of the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy)

“With the finalized plan of more than 3,700 miles—1,900 of which already exist—people can start to plan out how they will experience it,” said Brandi Horton, the vice president of communications for Rails-to-Trails. “This is big news for folks because they can already use it now, and see what it will look like when it’s finished.”

Horton says the route will be finished within the next two decades. That may seem like a faraway date, however, the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy has been renovating and building rail trails for more than 30 years, since its inception in 1986.

The route planning alone took a full year of deep analysis—the team at the conservancy needed to make sure that the trail’s direction adhered to a few guiding principles they had established for it, said Horton. Mainly, the conservancy wanted the trail to be on mostly flat ground with a sub-three-percent gradient, to not overlap any motor roads, and to provide recreational as well as tangible transportation benefits to communities along the way. Those goals were more difficult to achieve in some areas than others, especially in Western states, where there is less available infrastructure that meets the criteria.

“Railroads had a hard time getting through the Rockies, and a lot of what we have out in the West is mountain biking and climbing, these extreme sporting activities,” said Horton. Some of the largest trail gaps are in Wyoming and Montana. Addressing these gaps presents some of the biggest trail development challenges along the preferred route. “We’re taking our multiuse trail knowledge, and we’re extending it to a part of the country where people have never experienced it. The primary criteria for the trail is that it’s a multiuse trail—one you can bike, walk, rollerblade, wheelchair—and use it for a long-distance adventure or as part of your day-to-day life. As it’s connected, communities will have [access] they’ve never had before.”

The Cardinal Greenway in Richmond, Indiana. (Photo Credit: Jane Holman / Courtesy of Waynet, Inc and Rails-to-Trails Conservancy)

Horton stressed the immediacy and totality of impact the Great American Rail-Trail will have on local communities once it’s finished. From the reduction of automobile traffic and increased health scores that bicycle commuting provides, to the potential for tourism dollars, Horton attributes multiple benefits to multiuse trails in communities across the country.

The leg in Missoula illustrates how much change a multiuse trail network can make when implemented in a mountainous western state. From the time its first bike lane was striped in 1997, the town of Missoula has embraced cycling. The city currently has more than 22 miles of off-street trails (and more than 40 miles of on-street trails) for cyclists to enjoy. A 2016 survey by the American Bike League listed Missoula as the 10th-best bike commuting city in the country, with more than 6 percent of its roughly 70,000 residents using bicycles for their daily transport. And from 2017 to 2018 alone, the Missoula Metropolitan Planning Organization counted an increase of 10 percent in the total amount of bike commuters in the city.

“The importance of cycling to our community has been growing rapidly,” said Gaukler. “We’re currently one of the top bike-commuting cities in the country. With our existing bike network, locals and visitors in Missoula have the opportunity to park their cars and feel the outdoors while getting around town. That’s a big value for this part of the country. So having a multiuse network that allows people to bike to a trailhead, and then go for a hike or go fishing—all while enjoying the geographic and topographic assets of the area—it promotes a lifestyle that Missoulans enjoy.”

Gaukler notes that, beyond the recreational and commuting benefits, she also expects the Great American Rail-Trail to bring some ancillary advantages. She points to an increase in tourism dollars from long-distance and adventure cycling groups visiting towns as one major gain, but also mentions a less obvious reward—linking Missoula to federal and state lands. The Great American Rail-Trail will capitalize on an already converted section of the Old Milwaukee Railroad Trail, traveling east-west through Missoula, and connect with other existing bike trails that access federal lands surrounding the city, including the Pattee Canyon Recreation Area, the Blue Mountain Recreation Area and the Rattlesnake National Recreation Area and Wilderness. (In the Rattlesnake Wilderness Area, Gaukler said cyclists can legally ride on a 15-mile gravel road that was zoned to allow bikes and is surrounded on all sides by wilderness, something fairly unique given the ban on mechanized travel in wilderness areas.)

The rail trail will also connect to the heralded Bitterroot Trail, which runs 50 miles south of town and gives riders the ability to bike all the way to the sprawling 1.5 million pristine acres of the Bitterroot National Forest via separated bike lanes. And, through less established bike trails, the rail trail will connect to the more than 2 million acres of national forest land in the Lolo National Forest and to state parks like Travelers’ Rest State Park.

“If you’re riding the Great American Rail-Trail into Missoula, once you get here, there are all these other opportunities to branch off the trail to other existing trails,” said Gaukler.

Asked to reflect on what the Great American Rail-Trail will mean when it’s all finished, Horton is succinct.

“It will be a national treasure,” said Horton. “One that brings all these very different national landscapes across our nation into one unified outdoor space.”

To see the existing trails that will help comprise the Great American Rail-Trail, click on the location links below:

- Washington, D.C.

- Maryland

- Pennsylvania

- West Virginia

- Ohio

- Indiana

- Illinois

- Iowa

- Nebraska

- Wyoming

- Montana

- Idaho

- Washington

Editor’s note on May 7, 2019: REI has donated a total of $392,125 to the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy since 2003.