As you’re clipping a bolt on a climbing route, enjoying the moves and the view from up high, have you ever wondered about the person who put those bolts there? Or maybe you’ve questioned why they put the bolts where they did? What does it take to turn an unclimbed piece of stone into a classic climb? With well over 100 first ascents under my belt, most of which were bolted sport climbs, I’ve put in my fair share of work to create new routes. Here are the basics of how it happens.

The Vision

In the beginning, a route starts as an idea in the head of a climber, who looked up at a line and envisioned what it could be if it were cleaned, bolted and climbed. Before bolting, it’s important to check with local land managers, climbing organizations and the Access Fund to make sure new routes are allowed in the area, as regulations are specific to different locations. For example, power drills are not allowed in wilderness areas, but bolts can be placed by hand on these cliffs. And many climbing areas on U.S. Bureau of Land Management and Forest Service land don’t have specific regulations around bolting, but this can vary by area and it’s the developer’s responsibility to know what’s acceptable—or they could easily create a situation that could endanger future climbing access. Assuming there are no access issues with the area, and they know the regulations regarding what kind of public land their potential route is on, the hard work then begins.

The Labor

The developer then loads up their pack with all the essentials of route development: a cordless hammer drill, wall hammer, bolts, hangers, wrenches, a blow tube, brushes, a rope, harness, a rack of climbing gear, GRIGRI, ascenders, aiders, quickdraws, cams, slings, water, helmet, climbing shoes, static rope, the kitchen sink and more. Then they hike with their pack—probably bulging at the seams—to the top of the cliff. Sometimes this might be a nice, flat area that leads to the edge of the crag, but more often than not, it involves some sketchy third-class climbing, made even more treacherous by the 60-odd pounds of gear they’re carrying on their back.

After gaining their bearings at the top of the cliff and hoping they’re close to the line they had spied, they set up a rappel to lower down for a closer look at the rock face. If they’re lucky, they’d be close to the line and can carry on with the next step. If not, they’ll have to ascend the fixed line they rigged and try again.

Then comes the part that’s still hard work, but more fun: They get to put in an anchor and lower down onto their potential line to clean it of loose rock, scrub the holds free of dirt and debris, and figure out where to put the bolts. Route developers are typically experienced climbers who have climbed extensively across the country and often the world. It requires knowledge and experience from countless ascents, and a strong understanding of what makes for a good route, what makes for a poor route, and how to tell between the two. It’s not a good idea for newer climbers.

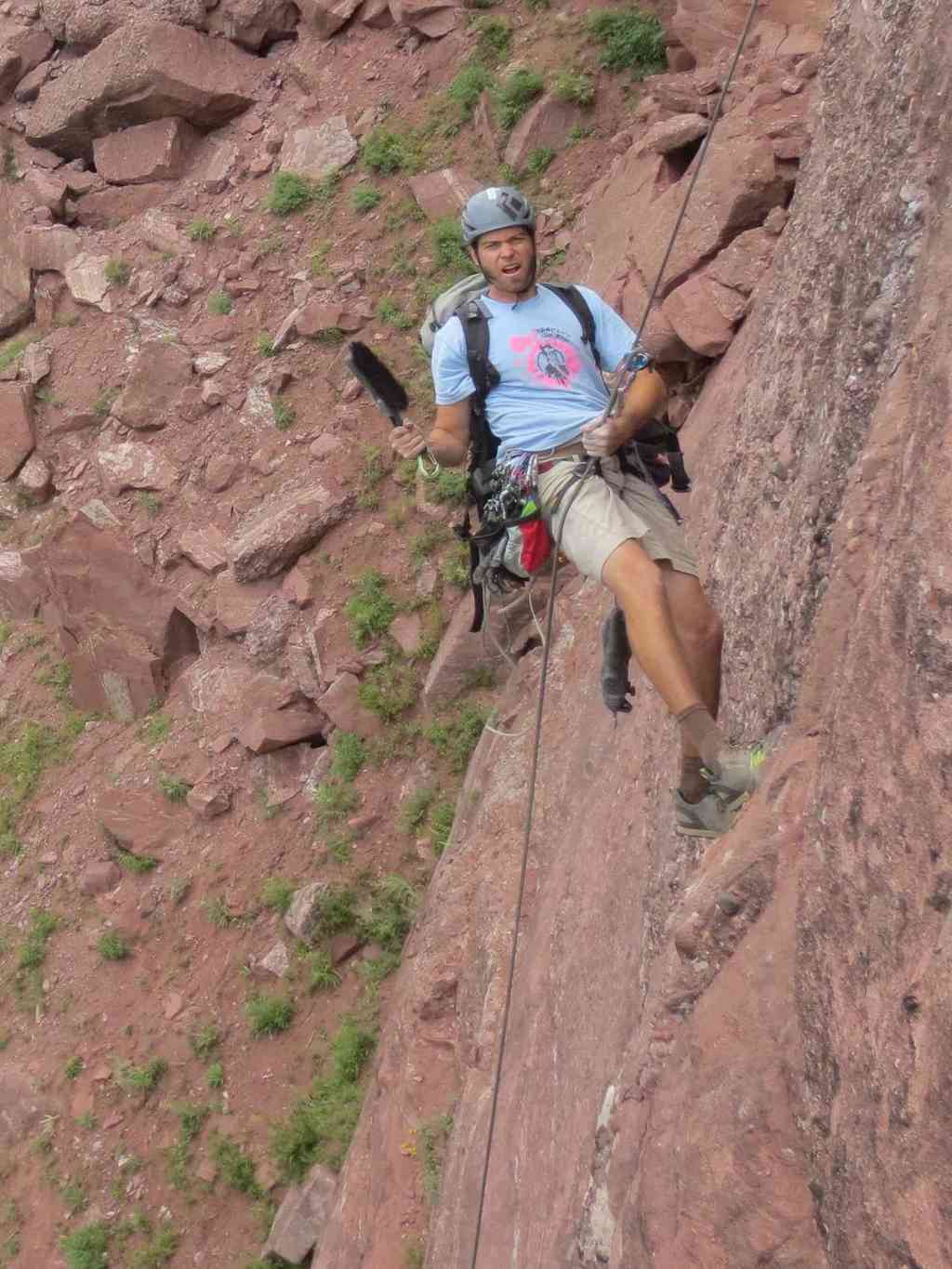

The author, cleaning a new route near Redstone, Colo. Photo credit: Ben Frye.

What Makes A Good Route

A quality climbing route needs to be an independent line, not too close to existing lines—that’s called a “squeeze job.” And it must be on high-quality rock that’s well protected by the standards of the area. In some places that will mean the bolts are relatively close together, but in others it could mean longer distances between them. Of course, with enough cleaning, prying and hammering, nearly any rock is climbable; but the best lines follow the cleanest, most solid rock. There have been times when developers have crossed the line from route creation to route manufacturing through tactics like chipping or creating holds, which is generally frowned upon, as it’s no longer accepting the challenge that the natural rock presents and will change the cliff forever.

Working Out The Moves

After the route is cleaned up a bit, the developer figures out the sequences—the best way up the route—and places the bolts. This is typically done solo, as it’s not much fun to hang out at the base of a cliff while your buddy above you trundles—pushes or pulls—off loose rocks and dirt. This means the developers are rope soloing—climbing on a fixed rope with a device like the Petzl Micro Traxion, which catches them if they fall—dialing in the moves, with no one for company but the lizards scampering across the cliff. Once they figure out where the best rock is for the bolt placements, they drill a hole and pound in the bolt, tighten it to proper specs, and repeat this process until all the hardware is installed.

The First Ascent

Finally, it’s time for the most fun part. The developer will come back with a partner and attempt the first ascent. If it’s a route well within their ability level, they might send it on the first go, since they know a lot of the beta from working on it. If it’s harder, it could take anywhere from a couple tries to maybe even up to a year to get it done. As a side note: It’s generally considered bad form to climb on someone else’s route and nab the first ascent before they do. They put all the work in, paid for the hardware and cleaned it up, so most climbers understand that the developer should be given a fair chance to climb it first. Most developers will mark their climbs that are in progress with some kind of tag on the first bolt, historically a red one; so if you see this and wonder what’s up, please don’t climb the route, as it’s not yet ready for the masses.

If all goes well, and they successfully complete the first ascent, the route is then opened up to the public. They might keep it to themselves for a while, or they might share it via word of mouth to the local community, or maybe even post it on Mountain Project. Eventually, it will become something many people can enjoy.

Route development is hard work—really hard work—and takes the place of a day that could otherwise have been spent simply enjoying climbing on a previously developed route. So if you happen to meet a route developer, be sure to thank them. They probably aren’t looking for glory or fame, but a simple thank you goes a long way to keeping them stoked to continue growing the climbing opportunities in your area.