Only when his kayak flipped in the rapids did Jeff Marion—then a teenaged Eagle Scout—realize that wearing boots had been a bad idea. The spray skirt came off but the boots didn’t; their rubber lugs were wedged into the hull, and Jeff was upside down in the river.

It was an early spring day, freezing cold. “I got one leg loose, and the other was just stuck,” Jeff says. His friends were “canoeing like crazy” to catch up. Finally he wrenched the other boot free and came up for air. “I remember standing on the shoreline like it was yesterday,” Jeff says. “I’ve never been so wired in my life.” That was only one of several close calls in his thrill-seeking youth.

Jeff grew up exploring the caves, woods and rivers of Kentucky, and at 58, he still gravitates toward “high adventure.” But he is also a naturalist—he learned the names of wildflowers and birds from his mother—and he cares deeply about the impact that his activities and others’ have on the earth.

Now a research biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, stationed at Virginia Tech, Jeff’s specialty is Recreation Ecology, meaning he studies visitor impact to protected natural areas and consults with land managers to make visitation sustainable. By his account, he is one of four such scientists actively conducting research in the U.S., and he has mentored most of his colleagues. The research studies that Jeff and his graduate students undertake are driven by one central question: Are we loving our parks and wildernesses to death? “Yes, to some extent we are,” says Jeff. “It’s essentially unavoidable.”

That’s a serious issue for the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. The trail is suffering from erosion and other damage, partly because the trail itself is unsustainable, and partly because visitors tend toward high-impact behavior. Even when they’re aware of Leave No Trace principles, if they aren’t compelled by what Jeff calls “ethical underpinnings” to use low-impact practices, they’ll end up trashing the trail.

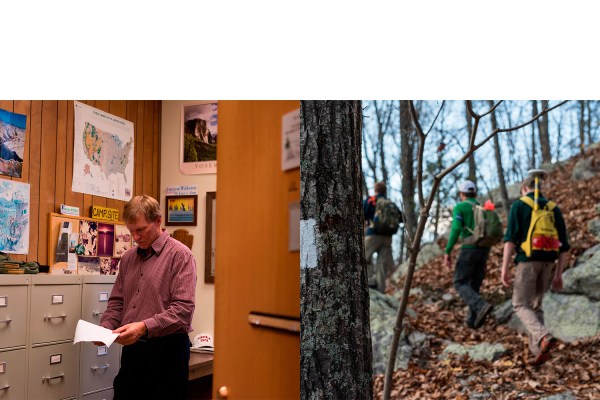

Jeff Marion measures erosion on the A.T. His research utilizes GIS computerized mapping and soil sampling to document trail damage.

The A.T. has a “warm, fuzzy place” in Jeff’s heart. He started hiking it in 1972, when he was in ninth grade, and after 43 years and 24 hikes, he finally finished it last September. “After so long hiking, it’s become a part of my life,” he says. When he reached Maine, his wife Susie joined him so they could summit Mt. Katahdin together, just as they had on their honeymoon.

Jeff loved the peace and solitude of his A.T. hikes, and his periodic immersions gave him the breaks he needed from being a self-described “workaholic.” But according to him, a recreation ecologist can never just enjoy a hike. On the A.T., “I’d stop and I’d say, Man, who the hell put the trail right here?” Jeff says. “And I’d get all bummed out.”

Each time a section of trail wears out, the A.T. stewards reroute it, which leaves erosion trenches behind. It’s a short-term fix that causes more damage over time. Jeff sent a proposal to the A.T. community with the question: “How do we make the A.T. sustainable so that we can put thousands of people up and down it every year, and it will be here in a thousand years’ time, and it won’t just wear away?” The result of that proposal is a three-year, $300,000 study with recreation fees paid by National Park visitors.

“I’m nearing the end of my career, and I really wanted to finish with a comprehensive study to end all studies on trails research,” Jeff says. “So I wrote it big.”

Left, Jeff in his office at Virginia Tech, where he is an adjunct professor. Right, leading research assistants Jeremy Wimpey, PhD, and Dylan Spencer on the A.T.

The study seeks to document not just the extent of the damage, but what’s causing it. The first thing to consider is whether the trail is in the right place. To determine that, Jeff’s team takes soil samples from different sections of the trail, and they also use cutting-edge technology like LiDAR data and GIS computerized mapping to help them analyze factors contributing to soil loss. “Once we understand that better through science, we can go out and design new trails that will avoid those things,” Jeff says. “So the next time we have to relocate part of the A.T., we’ll be moving it to a spot where it will stay in good shape forever.”

The second thing to consider is how visitors are using the trail. That’s where Jeff’s knowledge of Leave No Trace comes in—as one of the founding members, he literally wrote the book on the subject. But he’s most passionate about teaching young people. “My forte is experiential teaching out in the woods,” Jeff says. “A lot of the kids that grow up in urban areas are looking at screens all day long and they probably aren’t candidates for successful Leave No Trace education, because they don’t have a personal connection to nature. And that’s a little scary, quite frankly.”

Jeff is on his 11th year with the Venture Crew, a co-ed group facilitated by the Boy Scouts. He had been a scoutmaster for his son’s troop, but he switched to Venturing when his daughter turned 14, so she and her friends could go on high-adventure trips, too. The crew he leads is still predominantly girls. “I am exceptionally impressed by the young women today,” Jeff says. “They are so empowered, competent and active in outdoor pursuits.” His 14–18 year-olds not only gain confidence and wilderness skills, but inevitably become Leave No Trace ambassadors. The Boy Scouts also study his book, which means Jeff is reaching millions of kids. “When I’m on my deathbed, that’s what I’m going to remember,” he says.

Jeff keeps backpacking and climbing gear at hand for himself and his graduate students, who are invaluable to his research on the A.T.

The less inspiring alternative to education is regulation. The A.T. is considering limiting access to meet carrying capacity, as some other parks have done. It would be a reversal for the National Parks Service, which is running the “Find Your Park” campaign to attract younger and more diverse visitors, not turn people away. It’s an option Jeff is working hard to avoid. “The gate will get bigger and higher, you know? I’d always rather have education succeed.”

Between science and education, Jeff is completely optimistic that the trail will win. “We’ll dramatically improve its sustainability,” he says. “There’s no doubt in my mind that we will. The research has already led to a lot of new knowledge that will help us build a better trail.”

Meanwhile, on top of saving the A.T., venturing with teenagers, and raising the occasional llama, Jeff is a steward of his own private ecosystem. He had become concerned by the disappearance of toads near his home, so he built them a pond. The first year, “2,000 tadpoles turned into little tiny toads and dispersed.” He’s sure that hundreds of his toads have survived. His next project was repopulating the newts, but the bullfrogs have been eating them. So this year, the scientist plans to play God. “The bullfrogs are going to go for a ride.”

Learn more at REI.com/trails.