Mike Gauthier’s micro claim to fame, he says, is that he has climbed 31 routes on Washington’s Mount Rainier—probably more routes than anyone else, he suspects. After all, he did write the book on it: Mount Rainier: A Climbing Guide. In all his time on the mountain as a guidebook author and former chief climbing ranger, he’s been witness to receding glaciers and changing ice pack. With that, the climbing is changing, too.

Sensitive to temperature and precipitation, the 14,410-foot volcano’s more than two dozen glaciers—the most on a single mountain in the lower 48—magnify the effects of climate change, according to Paul Kennard, a regional geomorphologist at Mount Rainier National Park. And the melting rate has been picking up.

“From 1913 to 1994, for example, Rainier lost 25 percent of all its ice,” Kennard says. “And since 2003, they’ve lost an additional about 20 percent. So it’s accelerated.” This is part of a larger trend across the globe, with glaciers shrinking faster than before—and faster than previously thought—from the peaks of the Himalaya to ice sheets that terminate in the ocean, like in Alaska’s tidewater glaciers.

The Muir Snowfield, gateway to the most trafficked route on Rainier, has been losing about a meter of ice each year between 2003 and 2009, Kennard says. Even a year of heavy snowfall can’t make up for the increase in melting over time, he says. “It’s like a tide going out. You might have one big wave come in, but all that water is still going out.”

Through his time on the mountain and his photography over time, Gauthier has noted how this has affected the mountain’s climbing routes. Most notably, he says, access points where climbers get on or off a glacier are moving and routes are melting out earlier in the year. According to him, none of the climbing routes have become unclimbable yet. “The sky is not falling,” he says. “It’s not changing overnight. In 20 to 30 years [climbing Rainier] will still be a tremendous experience. But it’s changing.”

Here’s what climbers can expect to see in the future.

A rising firn line

As the climate warms, the line marking the upper limit of the summer’s snowmelt—or firn line—will move higher on the mountain, according to Kennard. “It’s way higher than in the early 2000s, maybe 1,000 feet or 1,500 feet higher,” says Jonathon Spitzer, director of field operations for Alpine Ascents. An IFMGA guide and former Rainier climbing ranger, Spitzer has nearly 20 years of experience on the mountain.

That means climbers will likely have to navigate around an increasing number of crevasses, cracks in a glacier that form because of the movement of the glacier, and travel on more bare ice. Kennard says climbing is “easier on firn, or last year’s snow, than on bare ice.”

That can affect day hikers, too, says Gauthier. “We’re seeing a lot more ice and crevasses on the Muir Snowfield, which is the primary route and a popular day hike. The result is that there’s more of a chance of people slipping into crevasses.”

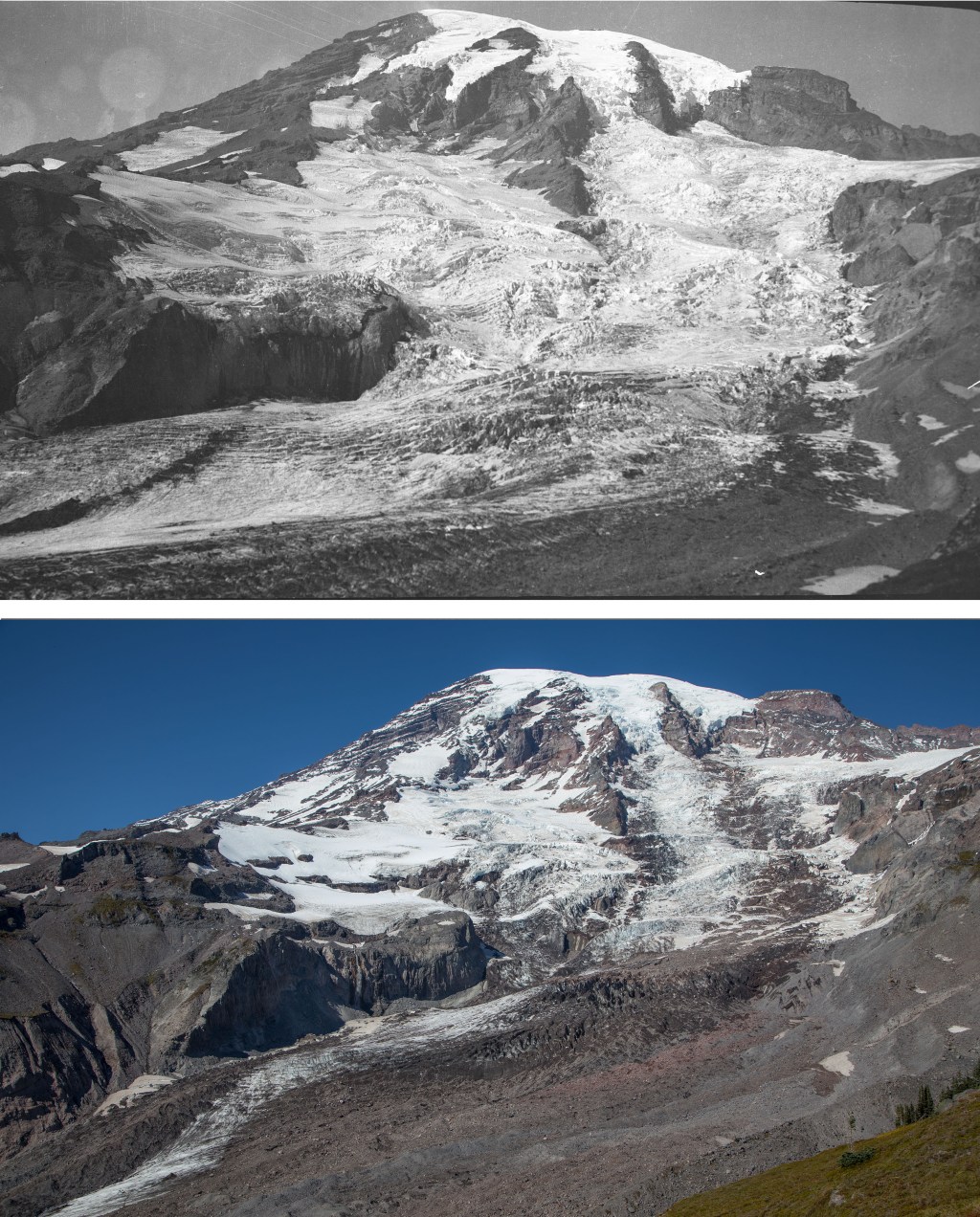

The Nisqually Glacier is likely the most visited of Mount Rainier’s glaciers, according to the NPS. Top: Historic image (1910) by Francois Matthes; provided by University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections (WAS3111). Bottom: Contemporary image (2017) by John Marshall for The Nature Conservancy (Photo Courtesy: The Nature Conservancy)

Shifting rock conditions

“The rock is really bad on Rainier. It’s choss,” Kennard says, meaning the rock is loose or unstable, making it difficult or unsafe for climbing if it’s not held together by ice. “And we know that subsurface ice, some sort of permafrost, has to be melting. And it seems to me that’s going to affect rockfall.” Kennard says he hasn’t seen research specifically on how fast that subsurface ice is melting, but just because there is no data yet doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem.

“I know for a fact that the glaciers are shrinking on the sides, pulling away from the rock and from the lateral moraines, so the rock is no longer being buttressed by ice. Those two things—the melting subsurface ice and the fact that the ice is pulling away from the rock—are going to increase your rockfall. And as we know, rockfall is already a significant hazard on several climbing routes.”

During the most recent climbing season, rockfall on the Liberty Ridge route, considered by the National Park Service as “the hardest and most dangerous regularly climbed route” on the mountain, killed one climber and injured two others.

In recent editions of his guidebook, Gauthier added notes about rockfall danger on the Liberty Ridge route. “I have definitely noticed there is more rock exposed, less snow and ice, and warmer summers, and that leads to more rockfall,” he says.

New camp challenges

Kennard supposes that people will increasingly have to camp on ice rather than snow. With more ice exposed, securing items like tents in camp can get tricky in high winds. “Unless they’re using ice screws, they’ll need new methods to secure tents,” he says. He also points out that more icy, crevassed terrain can increase the length of time it takes parties to climb the mountain, adding to considerations about the number of overnights.

Shortening and morphing climbing seasons

With climate change’s effects on Rainier’s glaciers, the favorable climbing season is expected to get shorter on certain routes, Kennard says. From Gauthier’s perspective, there are always abnormal years, but the overall trend is that many routes are melting out earlier or becoming more circuitous. “Routes like Fuhrer Finger and Ingraham Direct and Gibraltar Ledges used to be climbed more in late spring and early summer, and now those sometimes don’t even make it to summer anymore, falling into disrepair by May.”

Spitzer points to Liberty Ridge as another example of routes that have changed already. “The technical climbing is low down, where more snow is being melted,” he says. “The climbing window used to be much longer, now it’s earlier and shorter.”

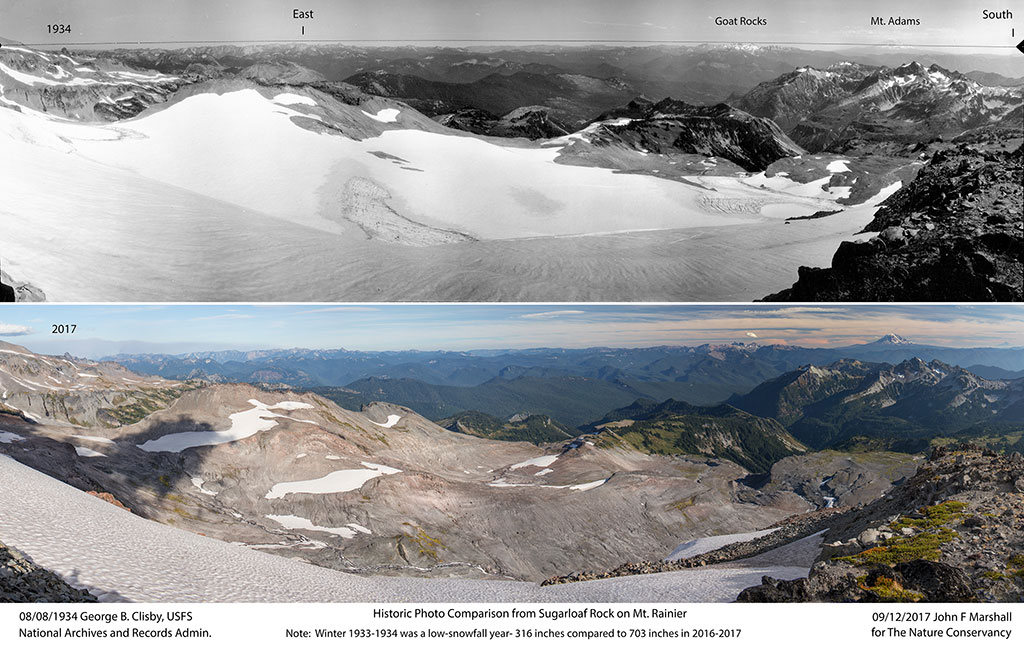

Photo Courtesy: The Nature Conservancy

Unpredictable melting

Stagnant ice—ice that’s not being replenished by more snow than it’s losing to melt—can create some interesting phenomenon, like rivers on the ice that flow down into a crevasse, making a waterfall. But that same stagnant ice on Rainier is also associated with glacier outburst floods. “It will be a beautiful, sunny day, when suddenly the Nile is coming out [of a glacier] for 10 seconds, which can turn into a debris flow,” Kennard says. “These are super high consequence, but infrequent. If you hear it—it sounds like a freight train—go perpendicular to the flow, upward.” These types of floods have occurred historically, but as the contrast between snow accumulation and melt gets higher, he can’t see there being fewer of these types of events.

Park access issues

As increased flooding and debris flows from larger, more frequent storms bring down higher amounts of sediment from the quickly melting glaciers, the riverbed alongside Paradise Road—the most popular and only year-round access point to the park—has risen 30 feet in places since 1910, Kennard says. “The sides, the banks, don’t get higher,” he says. “So rivers can handle less water.” That means roads are increasingly susceptible to damage from flooding and erosion. “You could lose access to the park.” It’s one of the main problems he’s working to solve in his role as a geomorphologist at the park.

The park did close for six months following a massive flood in November 2006 that washed out roads and damaged trails and campgrounds. Kennard says that certainly affected winter climbing on the peak. And last month, damage from a much smaller glacier outburst flood caused a road and trail within the park to be closed.

Evolving skill set required

As Rainier’s terrain morphs, climbers will need to adapt their expectations and skills, Spitzer says. Places that used to typically hold deep snow are now firm snow, he says, and spots that used to be firm neve—fresher, more granular ice or snow that hasn’t yet been compacted into ice—are now hard ice. Self-arresting on ice is much more difficult than on firn or snow. So being skilled with using crampons, ice axe self arrest and glacier travel skills will be even more important, Spitzer says, as well as hazard assessment, navigation and crevasse rescue.

Also, bergschrunds—crevasses that form near the upper end of a glacier between moving ice and stagnant ice—and moats—the gaps that form between rocks and glaciers—are changing and melting out more quickly, Gauthier says. Negotiating those sections, as well as the expected increasing number of large crevasses on the upper mountain, could require additional rope and climbing skills, and could possibly add to the time and effort required for Rainier ascents. Theoretically, Gauthier says, that could mean more time spent at higher altitude, and therefore increased risks of other issues, from sunburn to the effects of altitude.

Spitzer urges climbers not to feel rushed, though, and to take their time to be safe: “Learn the skills beforehand to be self-sufficient and manage hazards, and if you’re unsure about it, take a course or hire a guide.”

Read More: