“Imagine if you’re a kid and you’re at the edge of Sherwood Forest—you know, Robin Hood—and it’s like, oh, it’s that dark foreboding place,” says Rick Allen.

Allen, 33, and his wife Joanna Tang, 35, are scuba divers and these woods are underwater, one of California’s vast kelp forests.

“It’s a little spooky as you’re going in. But then, the second that you do go in, it’s like [you] look up and there’s this stained-glass ceiling above your head where the sun is filtering through these golden kelp blades, lots of green, gold and yellow hues, lots of browns. Then of course that filters down into the blue of the water and it’s just … it’s gorgeous,” says Allen.

Allen isn’t just diving for fun. He and Tang are part of a vast network of citizen scientists—regular folks who are helping researchers understand and protect oceans, mountains and other wild places.

The ocean is one of the most important ecosystems on the planet, producing more than half of the world’s oxygen and containing 99% of the habitable space on Earth. It’s also mind-bogglingly vast—the Pacific Ocean alone covers more area than the planet Mars. Even with all the marine scientists in the world, we’re critically underinformed as to the health of its ecosystems and how they’re faring in the age of climate change.

Diver Joanna Tang (front) and another Reef Check volunteer at Ship Rock, off California’s Catalina Island. (Photo Credit: Rick Allen)

Marine scientists are looking to close that gap, but they aren’t the only ones. Every year, millions of surfers, divers and sailors also take to the water.

By equipping and including these athletes in monitoring our world’s waterways, scientists can expand our ability to study and understand them. Citizen scientists are now collectively fueling numerous scientific endeavors and informing public policy that affects those waters. And for those going out into the wild, it’s changing how they engage with nature.

***

The organization Allen works with is called Reef Check. Founded in 1996, Reef Check works in more than 90 countries and territories to monitor and protect reefs. In many areas, it’s coral reefs, but in California they also monitor rocky reefs—craggy landscapes full of nooks and crannies that are home to many different species of algae, fish and corals—and kelp forests.

Allen first got involved with Reef Check in 2018, about a year after arriving in California from Chicago, where he learned to dive in a former limestone quarry. Allen works in a dive shop and the story goes that he and Tang were on a diving trip to the Farnsworth Bank, off the coast of Catalina Island. While they didn’t know the other people on the boat, a lot of the other divers seemed to know each other. Allen asked how they’d all met. They said Reef Check.

“It kind of turned into a recruitment day for them,” joked Allen. He and Tang signed up for the next round of training and species-identification lessons. Within a few months they were out in the water themselves.

Reef Check’s modus operandi relies on a scientific technique called “taking transects.” Volunteer divers go to a site and swim along in a straight line, taking notes about fish, algae and other sea life in the vicinity. Over time, these data points coalesce into a picture of the reef or forest, from tiny snails to apex predators.

A Reef Check diver practices writing species names and population numbers on a data sheet underwater during the pool portion of Reef Check training. (Photo Credit: Rick Allen)

Kelp forests, like terrestrial ones, support a wide array of species. But, they’re also vulnerable to changes in water temperature, acidity and in some areas kelp-munching sea urchins, which were once kept in check by sea otters, but have reduced many kelp forests to barrens.

Reef Check has been monitoring these changes, providing data to scientists and policy makers such as the number of fish or sea urchins in a given area or how those numbers have changed over time. Its California data has been used in more than a dozen scientific publications and reports. The organization has also partnered with state agencies and other monitoring programs to establish species population baselines for marine protected areas, which will help the state detect such things as a sudden increase or decrease in species’ numbers.

“It’s wonderful to see the data being used,” says Karen Selin, 60, a doctor and medical director at Humboldt State University in California. “Our data, our citizen science data, is being actively used by scientists, by state regulatory agencies.”

“It’s nice to take what you love to do and have it matter to the species that you’re diving with, you know?” continued Selin.

Allen said the species-identification training Reef Check gives its volunteers has also transformed the way he dives.

A group of Reef Check California volunteers pose for a photo before heading out to conduct underwater surveys in California’s most northern Marine Protected Area, Pyramid Point. (Photo Credit: Tristin McHugh, Reef Check California)

“It’s giving you words to describe what you’re seeing,” says Allen. He and Tang are now the type of people on the boat who will excitedly chat about what they’d seen, like shaggy sea palms and rock-like abalone, after a dive.

Divers have been expanding citizen science in other areas too. In Australia, for instance, divers have been submitting underwater photographs to help track manta rays through a program called Project Manta.

“The area that we are trying to cover around the Australian coastline is vast,” says Ph.D. candidate Asia Armstrong. “We can’t be out there all the time, whereas there’s always people in the water. And so it just multiplies our eyes.”

Much of the work divers are doing is based around reefs and other near-shore areas, but other citizen scientists range even farther afield.

***

Susie Goodall, 30, has worked on sailboats since she was 17, though her first experience on a boat happened back when she was just 3.

“Sailing is kind of the place where I feel normal,” says Goodall.

Goodall likes to sail long distances. In 2018, she took part in the Golden Globe Race, a 30,000-mile solo, nonstop race around the globe—and she’s traveled back and forth across the Atlantic a number of times.

On some of those trips, Goodall performed a kind of little ritual. Every so often, after she traveled a certain distance, or when conditions seemed right, she’d leave the helm and take down the boat’s sails, killing its speed until it was still in the water.

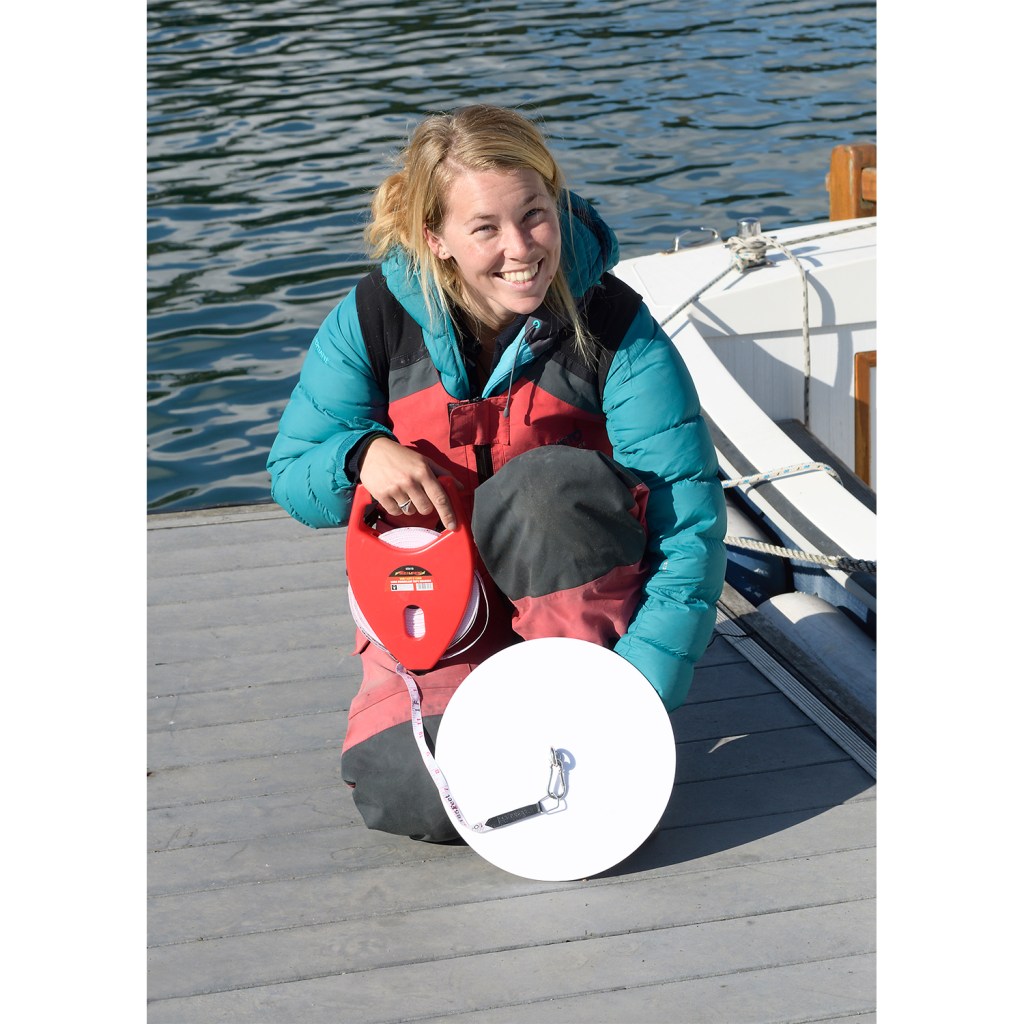

Goodall would then fetch a contraption—a Frisbee-size white disk attached to a tape measure—and lower it into the water, watching the 12-inch disk disappear into the depths, fading into the blue or green of the ocean. When it became impossible to see where the disk was anymore, she’d stop and record its depth and her GPS coordinates in an app.

Susie Goodall aboard her boat, the Rustler 36 Ariadne, in which she crossed the Atlantic ocean in 2017. (Photo Credit: The Secchi Disk study)

What Goodall was doing was taking what’s known as the Secchi depth, a way to measure the clarity and concentration of phytoplankton in the water. Phytoplankton are microscopic marine algae that underpin the marine food chain, but can be sensitive to changing ocean conditions. By measuring how clear the water is, scientists can estimate their abundance.

There are satellites and other ways to measure this remotely, but it’s not the same as being there (what scientists would call “in-situ”), says Richard Kirby, a U.K.-based scientist who runs the Secchi Disk global seafarer study.

“You can’t beat in-situ data. That’s not to denigrate satellite data, which is incredibly useful and has enabled us to learn a great deal about the oceans. But to lose in-situ data, just because you have satellites, would be an error,” Kirby says. And sailors, who tend to stay near their home marinas or follow certain, well-known passages across the ocean, are well suited to collecting years of local, in-situ data.

Goodall says one particular passage sticks out in her mind. She was crossing the North Atlantic, out in the easterly winds sailors call “the trades,” when she crossed over an invisible line and the entire ocean began to change.

“It was over I think a day-and-a-half, maybe two-day, period where all the phytoplankton was back in the water,” says Goodall. “It just became luscious green as opposed to blue.”

Secchi Disk project ambassador and yachtswoman Susie Goodall posing with a Secchi disk. (Photo Credit: The Secchi Disk study)

Had she not been doing the Secchi Disk work, Goodall says, she might not have have noticed as much.

“I think it helped me personally to learn the ocean a bit better. I mean, we know so little about the ocean. Think about how much we know about space. But what we know about the ocean is minuscule,” says Goodall.

“When you’re out there you kind of pay a little bit more attention if you know what’s going on. That’s why I just find it quite fascinating. What lives in the ocean? Why is it one color? Why sometimes green or gray or blue?”

She also felt it let her bring something back too.

“When you go out there for a job or for fun crossing oceans, it’s good to, I guess, bring something back,” she continued. “Because not everyone goes out there to the open ocean, you know?”

Both Reef Check and the Secchi Disk study require a bit of training and time commitment from their volunteers, but scientists are also experimenting with ways to get data from athletes without them even needing to pause their activities.

***

Constantly wracked by waves, the near shore is a rough place to try to put a sensor. If you try to build anything out there, build it strong, or else it’ll wash it up on the beach sooner or later. But out in those waves, there is a community that returns every year, no matter what the ocean brings—surfers. Waiting for the next wave, they sit, legs dangling in the water. In the meantime, they might be collecting valuable data.

“As a kid from Missouri coming to California, the very first thing I wanted to do was surf,” says Ryan Vaughn, 40. His family moved to the state when he was 12. Today, Vaughn is part of the Surfrider Foundation, an environmental nonprofit that focuses on beach and ocean conservation. From May 2017 to August 2018, Surfrider San Diego helped with a pilot test of a new device called the Smartfin.

Put out by the Smartfin Project, the fin is a device that looks like and functions as an ordinary surfboard fin, but also logs temperature, collecting valuable data as the surfers wait for the next big wave—data which can then be uploaded to a cloud database.

Vaughn was one of the surfers Smartfin tapped. Sometimes he’d get questions back on the beach from other surfers as to why his surfboard had blinking lights on it, but out in the water it felt just like a regular fin.

A surfer holding one of Smartfin’s pilot model devices, which can be attached to a surfboard to log ocean temperatures. (Photo Credit: The Smartfin Project)

And it lets him contribute to something that was already on his mind. “I was already a climate activist before I got involved with Smartfin,” says Vaughn.

Surfing was actually the activity that really got him interested in the topic.

“For me it is absolutely the surfing, the water. I’ve noticed that the water is warmer. That’s when I started to get concerned,” says Vaughn. “I knew what climate change was, I watched Al Gore’s movie in 2006, but kind of brushed it off like everyone else. And then a couple of years ago it became pretty clear to me that I was wearing a different wetsuit than I’d worn in the past. And to have something as large as the ocean be that noticeably warmer made me think like this is probably a big deal.”

“The surfing community is just inherently interested in the health of the ocean,” says Phil Bresnahan, the Smartfin Project’s senior research engineer. He’s an ocean athlete himself and has worked on other projects, like WavepHOx, a device that would collect data from paddle boards.

Bresnahan isn’t the only scientist looking at this kind of automatic data collection. One study from 2016 used 7,000 temperature profiles from dive computers worn by scuba divers, and in 2016 the Sonic Kayak experimented with attaching temperature recorders to kayaks.

Surfer Mike Sidebottom catches a wave in San Diego. (Photo Credit: The Smartfin Project)

Smartfin’s pilot with Surfrider wrapped up in August of 2018. They’re working on their next iteration of the fin, which they’re planning to test out and distribute in 2020.

Citizen science has caveats. It’s important to validate the data and make sure it’s unbiased and collected well, for one thing, and to ensure that volunteers understand how their data is being used and why. There are also questions around topics like the best way to keep people interested and how to make sure wild places are safe from unintended consequences, like photos accidentally revealing the location of endangered animals to poachers.

But in the end, the people most ready to understand how our wild places are changing may be those who explore them on a regular basis, and scientists are looking to the millions of surfers, sailors, divers and other athletes to help them study our planet.

“This is a really nice way for people to contribute, to give back to ocean health, while doing exactly what they love,” says Bresnahan.

Editor’s note: Surfrider Foundation is a nonprofit partner of REI. Since 2010, REI has contributed nearly $70,000 in grants to the Surfrider Foundation.