The most prolific North American climber of all time, passed away at 94

Fred Beckey, born Wolfgang Gottfried Beckey, was one of the most influential—perhaps the most influential climber—in American history. He died on October 30 in Seattle at the age of 94.

Born in Düsseldorf, Germany, on January 14, 1923, “Fred started climbing in the Boy Scouts,” according to a report by The Mountaineers, “and continued as a teenager with The Mountaineers, graduating from our Basic climbing course.” In 1939, as a 15-year-old, he joined REI co-founder Lloyd Anderson on the first ascent of Mount Despair.

At 19, Fred climbed the highest peak in British Columbia, Mount Waddington (13,185’), in the rugged Coast Mountains, completing the peak’s second ascent with his brother Helmy. He went on to climb many of the tallest peaks in North America, established long alpine routes in Canada and the Pacific Northwest, and did the first ascents of innumerable desert towers on the Colorado Plateau, a 240,000-square-mile area covering the Four Corners area of Arizona, Utah, Colorado and New Mexico.

According to accomplished American desert tower climber and founder of the climbing gear museum Vertical Archeology Ashby Robertson, “I’m not sure if anyone knows the exact number, probably not even him. Thousands of quality climbs though for sure.”

“Imagine a Moleskine notebook with all his notes in there,” professional climber and head of The North Face climbing team Conrad Anker told the Co-op Journal. Conrad was referring to an alleged hidden book of Fred’s first ascents (ranking well into the thousands) and dream-routes journal. “It’s rumored to be out there, and finding it would be like finding an undiscovered Beatles album.”

He was always rushing to the next project.

Many climbers, from the everyday to the elite, crossed paths with Fred over his long life, and they all have wild stories about the icon. “The truth about Fred, though, probably lies somewhere in the middle of all the hero worship and the often grumbling man,” Robertson said. “You really didn’t come up high on Fred’s radar, unless you were planning a trip with him or paying for gas.”

Some of Fred’s regular climbing partners in the American Southwest during the 1960s and 1970s included Harvey T. Carter, Layton Kor and Eric Bjørnstad (all three have since died), a veritable who’s who of American rock climbing. “He was always rushing to the next project,” Robertson said.

Steve “Crusher” Bartlett, author of the coffee-table book Desert Towers: Fat Cat Summits and Kitty Litter Rock wrote on Facebook: “I’m lucky to have roped up with Beckey, Kor and Carter, proud to have had the opportunity to capture something of these larger-than-life characters in my book. They learned their art the hard way and relied on their own skills and judgment.”

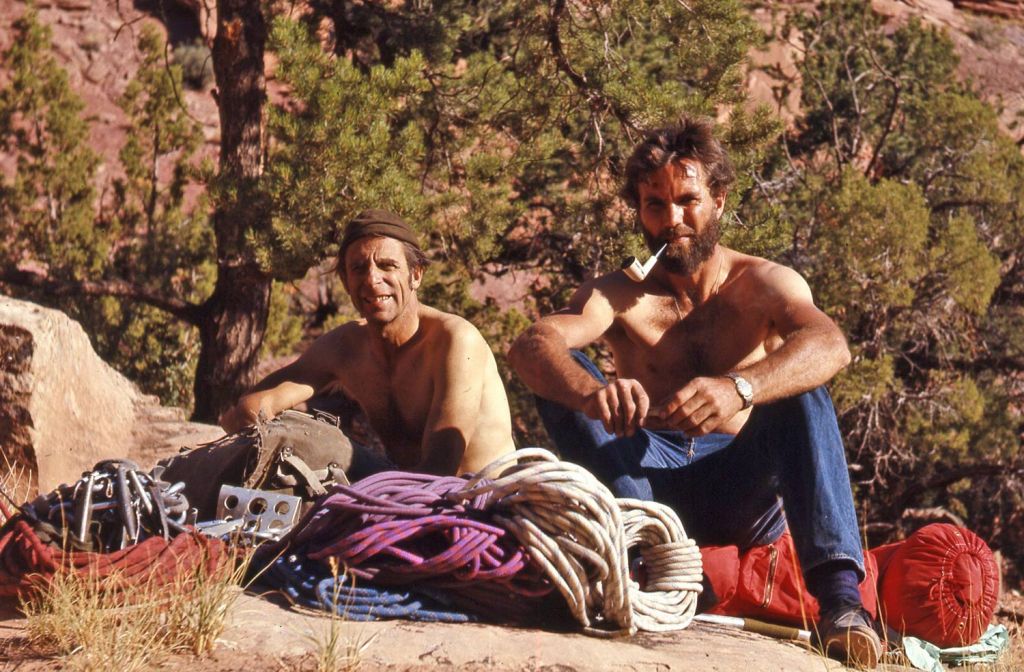

Fred (left) with frequent climbing partner Eric Bjørnstad in 1971 after a first ascent of Honeymoon on The Bride, near Moab | Photo: Eric Bjørnstad

It’s not just the quantity of Fred’s climbs but it’s their quality. Fred had an eye for a good line and when he was in his prime, all of the good lines were there for the picking. Many of his first ascents have since become classics. He kept loose-leaf binders and journals filled with notes on future climbing objectives, potential partners, available couches for sleeping, and details to include in his trip reports. This mass of information is likely the source of the “little black book” rumors.

Fred led a dirtbag lifestyle—eschewing societal norms in the relentless pursuit of rock—which he kept until he died. However, that was not the case when he was awarded the President’s Gold Medal from the American Alpine Club (AAC) during a black-tie event in New York City in 2015. There he was outfitted him in a crisp suit.

“The President’s Gold Medal is given very rarely—this is the fourth time it has been given in the Club’s 113-year history—for extraordinary accomplishments in the climbing world,” AAC President Mark Kroese told Climbing Magazine at the time. Aside from odd jobs in the late ’50s and the numerous books he authored, he never had a typical job. He never married or had kids. He was a rock climber. Everything else was secondary.

A 1970s snapshot from Fred’s eternal road trip | Photo: Eric Bjørnstad

He lived and breathed the vertical and was an unstoppable force in the mountains. “He was alpine climbing before anyone was doing it. Same with his desert climbs,” Conrad said. His diverse first ascent list varies from multi-pitch rock routes on Yosemite’s obscure Wawona Dome to British Columbia’s immense South Howser Tower in the Bugaboos.

His list of notable ascents continues for 13 pages on the American Alpine Journal’s archives. Notable areas include Wyoming’s Big Horn Mountains, Washington’s Picket Range, the Cascade Mountains in British Columbia, and Canyonlands in Utah (to name very few). Fred was not, however, a big expedition climber, especially after he was omitted from the 1963 American Everest Expedition—even though he had an attempt on neighboring Lhotse (27,940’) nearly 10 years earlier—that placed the first American climbers on the roof of the world. After that snubbing, according to Anker, possibly due conflicts during the Lhotse climb, he decided to travel and climb in smaller teams.

He devoted all his life, 365 days a year for three-quarters of a century to climbing.

Stewart Green, another climbing writer and historian in Colorado, remembered his friend Fred. “He was so motivated, much more than just about anybody else. Fred climbed all over the place and loved it. That was his whole life. It’s inspiring to think of what we can do if we put our minds to it like Fred. That may be his legacy more than his 5,000 first ascents.”

Legendary alpinist Jim Donini who appears in the climbing movie Dirtbag: The Legend of Fred Beckey told the Co-op Journal, “In a climbing sense, he was definitely the American original. I can’t think of anyone that epitomizes the modern or postmodern American climbing scene as he has.

“There is no one who has poked his nose and explored more mountains in North America than him. No one has left a climbing trail like that. He crossed more valleys, more ridges, than anyone. Nobody is close. He devoted all his life, 365 days a year for three-quarters of a century to climbing.

“He opened up the division for American climbers, as he was the first one to go into many areas and report on them. I don’t think his feats will ever be replicated. He was eccentric and relentless. He was an original and we’ll never see his like again.

“Farewell, warrior.”