The Long Ranger finished Colorado’s Centennial Peaks in 60 days. Here’s how he did it, how burritos aided his mission and what his accomplishment means to the rise of self-supported mega-adventure.

It was late afternoon, and Justin Simoni rolled to a halt at the bus stop on the outskirts of Boulder. Wet, cold and exhausted, he stopped just long enough to take a picture with his bike and the Boulder city limits sign before pedaling home, an inconspicuous conclusion to what was by all accounts an epic adventure.

Simoni at the finish line

Starting two months earlier, Simoni had pedaled from his house to the hundred highest peaks in Colorado, the “Centennial Peaks” as they are collectively known, in a single, self-supported push traveling only by bike and by foot.

Why?

“I don’t own a car. And I love mountains,” said Simoni.

The 36-year-old cyclist, climber and trail runner is known online as The Long Ranger for endurance feats such as the Tour 14er and Green Mountain Challenge. Simoni has a red-brown beard and bright eyes that are perpetually squinty—whether from exposure to sun or laughter, it’s hard to tell. A smattering of freckles dot most of his face and arms, another reminder of days spent outside. Though he calls himself as an introvert, he is an animated conversationalist, completely unable to remain still for even a moment. He shifts constantly in his chair.

A self-described lonely kid, Simoni has always looked for new ways to get out into the mountains under his own power. “You’re all alone, you have to do everything yourself—there’s no one to help you,” said Simoni. “It’s like being the best version of yourself.”

Simoni on Jagged Peak

And Simoni’s best version of Simoni is pretty darn good by any measure. He finished this 2,344-mile adventure—equal to the distance from Cleveland to Los Angeles —in 60 days, 14 hours, 59 minutes and 42 seconds. His route packed 384,184 feet of elevation gain, the equivalent of almost 13 summits of Mount Everest from sea level.

“The Highest Hundred is not easy,” said Anton Krupicka, a climber, cyclist and runner infamous for his propensity for squeezing multiple endurance sports into every adventure. “It takes venerable perseverance for a long period of time.”

“I trained like an alpinist with a mountain biking problem.”

To prep for this adventure, Simoni trained for seven months, running laps up Boulder’s Green Mountain, spending hours at the climbing gym and riding about 100 miles each week. Once, he ran up Green Mountain 13 times to gain the equivalent of Mount Everest’s elevation in a single day.

“I trained like an alpinist with a mountain biking problem,” said Simoni. “I’m not an athlete. I just like to have fun.”

Simoni on Longs Peak

To stay motivated on his grueling journey, Simoni uploaded his routes and summits to his blog and Strava. Knowing that people were following him and were perhaps inspired by his undertaking gave him the motivation to keep going when things got tough.

Challenges that Simoni faced included relentless rain during Colorado’s monsoon season, carrying 60 days worth of equipment and as much food as possible on a bike that he had to maintain himself, and staying on course on peaks and passes that often don’t see a single hiker in the summer.

“He takes a quirky, performance artist approach that adds interesting layers to the project rather than simply focusing on bagging peaks.”

Simoni, an artist by training, was inspired by land artists of the 1970s to combine endurance sports and adventure.“People have been undertaking all kinds of super long self-powered expeditions for a really long time,” said Joe Grant, fellow ultra-endurance feat-ist. “What I like most about Justin’s style is that, aside from the sheer physical feat of accomplishing such a challenge, he takes a quirky, performance artist approach that adds interesting layers to the project rather than simply focusing on bagging peaks.”

Some of his art is concrete, other works are more performative. He sees each line that he walks as an ephemeral work of art, disappearing almost as soon as it has been created. Though many might follow in Simoni’s footsteps, their experiences will be different—and it’s this difference that is so compelling to Simoni. He even includes an artist’s statement along with many of his expeditions. With the land as his canvas, he sees his feet as the brush and adventure as his primary artistic medium. That, and burritos.

To fuel his adventure, Simoni estimates he spent over $100 on tortillas alone. Breakfast burritos, peanut butter and Red Vines were staples of his expedition diet. Simoni’s challenging route was three times longer than the Tour Divide, took place mostly above 9,000 feet, and his need for fuel was huge: between 4,000 and 5,000 calories each day.

“I am so sick of peanut butter,” he said.

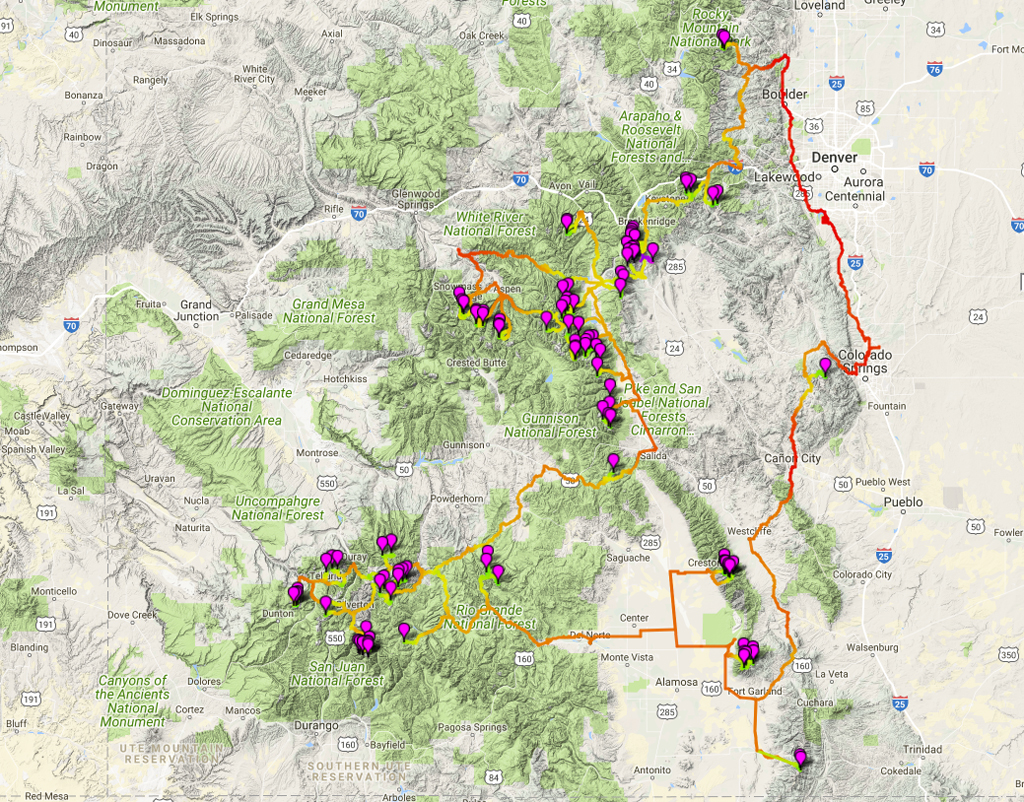

Simoni’s adventure

Simoni’s journey was logistically involved, to say the least. Piggy-backing off his 2014 Tour de 14ers, where he biked to and climbed all of Colorado’s 14,000-foot peaks, Simoni spent hundreds of hours poring over maps, data and charts to figure out an ideal route to connect the Centennial Peaks. Simoni is now working on a guidebook that he hopes will inspire other adventurers to use their bikes for approaches, including advice for first-time bike-adventurists.

“Social media just helps a lot to broadcast activities that were traditionally a bit more underground.”

While this kind of self-supported mega-adventure is nothing new, social media has allowed athletes like Simoni to gain a following online and draw attention to his athletic undertakings. With the availability of information on the internet, social media-based inspiration, and now even guidebooks, it appears that self-supported mega-adventure is gaining traction. “People have been doing this kind of shit for a long time,” said Krupicka. “I think social media just helps a lot to broadcast activities that were traditionally a bit more underground.”

Simoni hopes that his adventures inspire others to get out their front doors, onto bikes and head for the hills. “Start from home,” he said. “Give yourself plenty of time, and make it fun.”

What’s next for Simoni?

“I’m going to eat a really big pizza,” he said, ever living in the moment.