Mother Nature might not care who you are, what you do and what you look like, but online, fellow recreationalists just might.

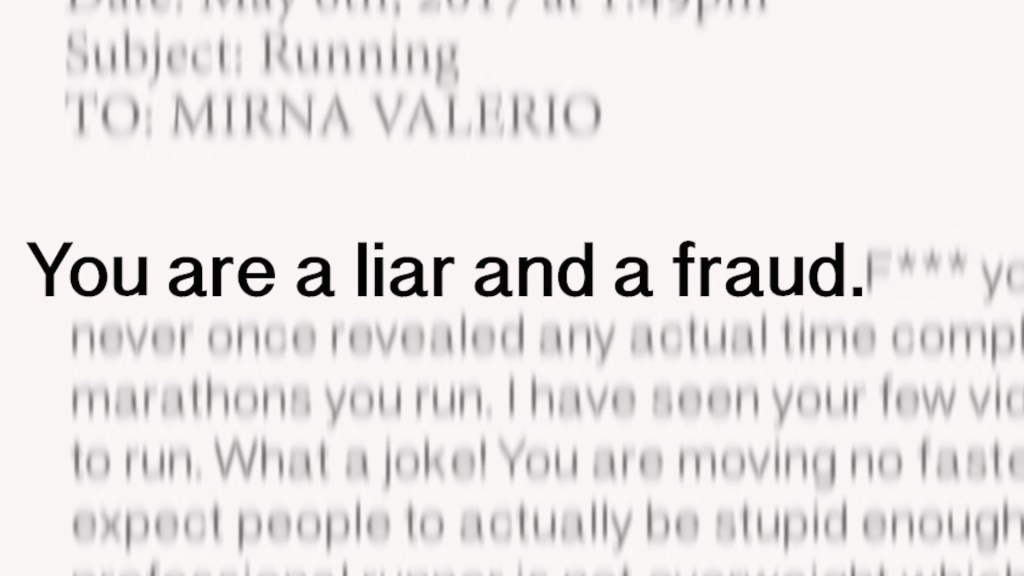

When we released three Force of Nature Co-op Films over the course of 2017, we realized there was a connecting theme we didn’t expect: online harassment in the outdoors. We set out to make films about strong women in the outdoors. As they came to life, a second storyline emerged: Shelma Jun of Flash Foxy, a climbing collective for women, has been harassed for speaking up about discrimination in the climbing world; professional ski mountaineer Caroline Gleich found herself in the midst of an online-turned-real-world harassment case; and while running an ultramarathon, Mirna Valerio received a cruel email calling her a fraud and a fake.

As members of the outdoor community, we like to think that although online harassment happens in our broader society, it doesn’t happen here. But that is simply not true. We are not immune.

We occasionally but consistently witness and moderate online harassment in our REI social media threads.

“While the online landscape can feel like the Wild West, we view our own social platforms as rooms in the co-op home. We always welcome dissenting opinions but when comments cross over into bullying or harassment, we step in,” said Laura Swapp, REI director of next gen marketing and Force of Nature lead.

After witnessing this trend of online harassment, we wanted to learn more about how much of an issue this was in the outdoor community, as well as find out what can be done.

By the numbers:

According to a 2017 study by the Pew Research Center and U.S. Department of Justice statistics:

- 66% of Americans have witnessed online harassment

- 41% have personally been subjected to harassing behavior online

- 21% of young women and 9% of young men report being sexually harassed online

- 1 in 5 Americans has been stalked, physically threatened or harassed over a lengthy period of time

- 1 in 10 has been attacked online due to appearance, race or ethnicity or gender

According to the REI online community management team, about 10 in 1,000 comments on an REI social media platform are moderated for bullying or harassment (and even 10 are 10 too many).

Online harassment can take many forms: stalking, impersonation, doxing (releasing victim’s name and address), trolling, leaking private images, sexual harassment, cyberbullying and hate speech, to name a few.

The three women featured in our Co-op Films are leaders in the online space. But they say that’s also opened them up to criticism. After founding Flash Foxy, Shelma Jun used her platform to write articles about sexism in the climbing community. She also used her reach to solicit feedback from the community about harassment in climbing gyms and published the results—and received a lot of negative feedback. Before becoming a professional ski mountaineer, Caroline Gleich got her start as a ski model—something people have criticized her for. She’s used her large Instagram following both to fight against this kind of criticism and as a platform for her environmental activism. Ultramarathoner Mirna Valerio is vocal on social media, in articles and most recently in her book about the need for body positivity in the outdoor world, a view espousing affirmation that a small online faction take issue with.

Shelma Jun says she has been harassed in many ways—trolling, hate-filled emails, name-calling and character assassination. “Apparently I’m a lot of things: I hate men and I wasn’t loved enough as a child. I’m a complainer, whiner and I bring politics into the outdoors,” she said.

Shelma Jun climbs in the REI Co-op film “Within Reach.”

Studies on the topic show there are a number of things that exacerbate the issue of online harassment, like multiple perpetrators, offline contact, power imbalance and repetition. Shelma pointed to the public aspect of the behavior. “People want to shame you or chastise you or ridicule you in public. They don’t want to take the time to write you an email that no one will see,” she said. And that’s one of the problems—because commenters can hide behind their screens, there is often little to no consequences for their actions, making cruelty that much easier.

According to that same study by the Pew Research Center, 35 percent of women who have experienced any type of online harassment describe their most recent incident as either extremely or very upsetting. What starts as an online problem can lead to offline consequences.

Shelma has lived firsthand the effects of online harassment and spoke to us about the anxiety that comes from being targeted. As she spoke out about sexism, people began writing offensive and derogatory comments in climbing forums, Facebook threads and Instagram. “It eats at you. When you write [articles and social media posts online], you get anxiety about the backlash. It affects your psyche and your confidence. Everything feels like a personal attack on your character,” Shelma said.

She’s not alone. For years, Caroline Gleich was harassed by an online bully who eventually crossed the line into the real world; he found her number and left her a disturbing message. “When I was dealing with it at first, I had no idea it was harassment. I thought it was part of being a public person. I told myself to be tough,” Caroline said. She spent years ignoring increasingly jarring messages online until she received that phone call in 2016 that catalyzed her to take legal action.

It became impossible to open her social media accounts without bracing herself for online vitriol. She started censoring her writing. Then, she noticed her anxiety about online forums started impacting her real life too—she stopped doing public appearances, she didn’t ski with strangers on trails. “It’s so deeply traumatic you want to ignore it and you want it to go away. But it changed my personality,” she said.

In our own channels, we see small numbers of online harassment, and have a zero tolerance policy for this behavior—both online and in the workplace. “At the co-op, we believe the outdoors is for all. To cultivate an inclusive and welcoming place, we must manifest a zero-tolerance approach to harassment in all its forms and to intercept and stop it when we see it’s happening,” Laura said.

Online harassment happens in the outdoor community, but does it happen in real life, while recreating? The short answer is: yes. We spoke to Erin Berger, assistant editor at Outside magazine, and author of “Don’t Care About Sexual Harassment? Don’t Read Outside.” Outside launched an anonymous sexual harassment survey in November 2017 and staff have been sorting through the responses.

According to their early findings, 70 percent of readers have been harassed while recreating. That wasn’t all. “I was surprised by how many people (44%) have been followed—runners, hikers, cyclists. They’ve been threatened, screamed at, catcalled. A lot of industry people had the story of inappropriate things happening in professional settings,” Erin said.

With movements like #MeToo representing how widespread sexual assault and harassment are in our society, and an increasing number of public sexual misconduct allegations against public figures, the issue is now at the forefront of popular discourse. Like all corners of society, the outdoor community is not exempt from issues in the broader culture.

Outside received plenty of backlash from commenters on social media channels. With a plethora of comments like: “I’m so mad that you guys are doing a poll like this. I read your magazine to get away from the life. … I get enough political bullshit when I turn on my TV or log into social media and at work.” They even received jokes about sexual harassment and assault.

Mirna Valerio receives a cruel email in the REI Co-op film “The Mirnavator.”

The magazine’s editorial staff will be sharing more of their findings in their March issue—which focuses on sexual harassment in the river-riding industry. Stay tuned.

So what can we do about online harassment? Here at REI, we step in quickly when we witness bullying behavior. Depending on the tone, tenor and content, we may remove the comment and block the sender. If comments are on headed down a path we foresee veering into dangerous territory, our community management team may step in with a reminder of how we treat folks in our space. “We are always monitoring our online community to make sure it’s a healthy, welcoming place where people can respectfully voice their opinions. No name calling, no slurs, no humiliation, no threats. We just don’t have room for it,” Laura said.

There are also scientifically-backed steps we can all take together to curtail online harassment when we see it.

Lisa M. Jones, Ph.D., a research associate professor of psychology at the Crimes against Children Research Center (CCRC) at the University of New Hampshire, has spent years studying the effect of cyberbullying on young people. Her research shows that bystanders—anyone who is a witness or hears about harassment or bullying—can have an impact. If you notice a harassment or bullying situation, in person or online, stepping in can be the single most effective thing you can do, she says.

Lisa continued, “If it’s been going on for a long time, if there is a lot of aggressive sexual or biased language or multiple perpetrators, research tells us that these are situations where victims are going to be really emotionally impacted.” There are a few simple steps to take in situations like these.

First, the research tells us, ask the bully to stop. If that doesn’t work, don’t provide an audience (or, colloquially, “don’t feed the trolls”) and don’t respond aggressively—as that can heighten the bully’s actions. Finally, and most importantly, follow up with the person who was targeted—make sure they are OK and that they know how to report the incident, should they want to.

If you yourself are a victim of online harassment, ConnectSafely.org has a few tips for cyberbullying: One, ignore the bullying in the hopes that without a reaction it will stop. Two, block the bully from your social media accounts. Three, keep diligent digital and hard-copy records of persistent bullying. Four, reach out to a trusted friend or family member, your social media platforms and/or local law enforcement for help. Five, use your available tech tools. Facebook, Instagram and Twitter all have their own ways to report abuse.

Caroline Gleich skis in the REI Co-op film “Follow Through.”

If you see online harassment, you can (and should) report it. “The best thing you can do is try to stop the bullying by taking a stand against it. If you can’t stop it, support the person being bullied,” writes ConnectSafetly.org. Follow the above social media platforms reporting tools to stop any online harassment you witness.

Hopefully harassment doesn’t move from online to offline, but if it does the Forest Service has advice for how to stay safe in the outdoors, like traveling with a companion, leaving your itinerary with a friend and bringing emergency supplies. At REI, we offer select outdoor safety classes, and encourage everyone to check with their local police departments for self-defense classes.

When we feel the need to comment online, remember: “Words matter. What you say matters. Be thoughtful about the way you speak out online. There is a way to be firm in what you believe in that isn’t degrading someone else or attacking them,” said Shelma.

“It’s our job—both as REI members and as human beings—to be courageous and empathetic and to call out inappropriate conduct,” Laura said. It’s easy to dismiss the lasting, devastating effects of online harassment as avoidable, but it’s a real issue. And we have the power, and responsibility, to stand up and stop it.