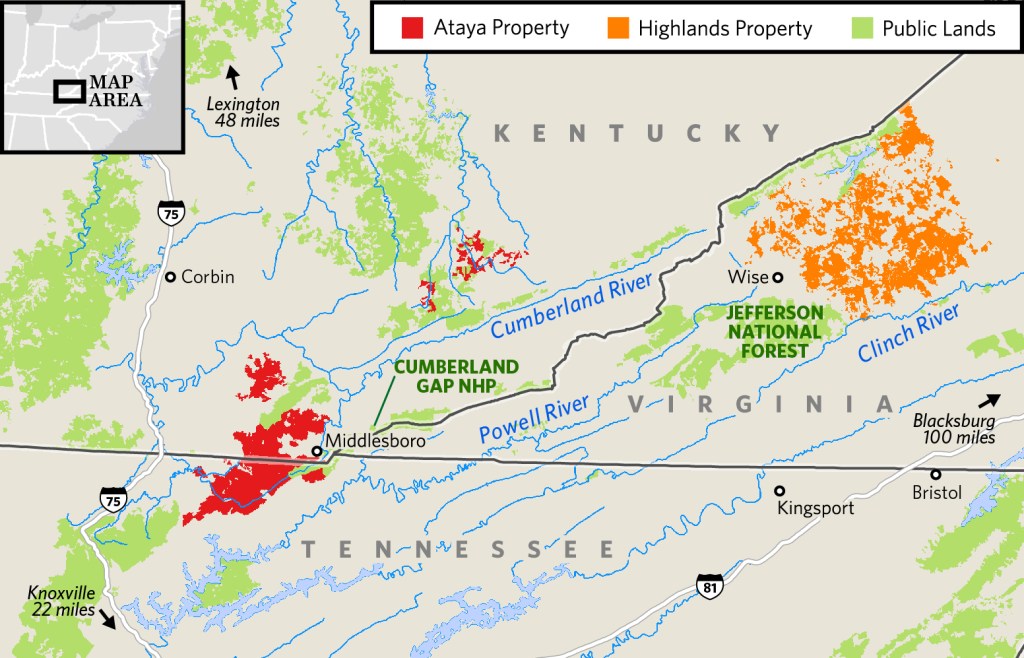

A 253,000-acre swath in the Central Appalachian Mountains will be protected, thanks to a land acquisition by The Nature Conservancy (TNC) announced earlier this month. Two parcels, one along the Kentucky-Tennessee state line, and the other in Southwest Virginia, will fill in large gaps between existing public lands and provide a wilderness corridor for animals seeking refuge from climate change, experts say.

The acquisition, known as the Cumberland Forest Project and announced July 22, is among the largest land purchases TNC has made in the Eastern United States. The organization is celebrating the deal for the way it will connect wild lands along the Appalachian Mountains.

“You see a lot of green spaces on the map when you look at the Appalachians,” says Brad Kreps, director of TNC’s Clinch Valley Program. “But there are a lot of gaps within that conserved network, and those are the places we need to work to serve the entire Appalachian corridor. The Cumberland Forest Project is a strategic acquisition that helps stitch together other protected lands and helps us maintain connected wildlife habitat.”

The tracts comprising Cumberland Forest don’t contain the most pristine forests in the Central Appalachians, representatives from The Nature Conservancy say, but the land may serve a vital role in the face of global warming. As temperatures rise, animals will retreat to the Appalachians in search of cooler climates and the new parcels will help facilitate that migration. The Cumberland Forest is already home to endangered species such as the golden riffleshell mussel and the pygmy madtom, a small catfish found only in two rivers in the Southern Appalachians.

A map details the Ataya and Highlands properties comprising the 253,000-acre Cumberland Forest Project. Existing public lands are shown in green. (Map Courtesy: The Nature Conservancy)

The first of the two parcels, the Ataya property, is a 100,000-acre tract running along the Kentucky and Tennessee border near Cumberland Gap National Historical Park. The Highlands property, the second of the two plots, consists of 153,000 acres of forest in Southwest Virginia, sandwiched between Jefferson National Forest and Breaks Interstate Park. Both parcels were previously owned by timber companies and managed primarily for resource extraction, from logging to coal mining.

The Role of a Working Forest

The Cumberland Forest is more than just a land deal, Kreps says. It’s an opportunity for TNC to restore the landscapes and manage them as working forests that can help support local economies. A working forest is a parcel of land that makes environmental protection and restoration a priority while still allowing for timber harvesting. This is done through science-based harvesting certified by the Forest Stewardship Council, an international nonprofit that sets global standards for sustainable timber.

“The working forest model represents an evolution in the thought process of TNC,” Kreps says. “We realized we needed to come up with an approach that met that balance of conservation and local economic need.”

Kreps helped spearhead the concept of a working forest for the TNC on a smaller property in Southwest Virginia called the Clinch Valley Program, which began 15 years ago on the banks of the Clinch River.

“We showed that we can support local economies by employing local loggers and sending products to the local mills while improving the environmental condition of the forests and streams,” he says. “With the Cumberland Forest Project, we’re scaling up that model.”

Seth Zuckerman, executive director of the Northwest Natural Resource Group, which helps private landowners develop sustainable management plans, says the working forest model is a viable one.

“Many people are rightly skeptical of timber harvests because they’ve seen so much of it done for short-term financial gain,” Zuckerman says. “But most forests with the exception of old-growth forests benefit from thoughtful human stewardship.” To achieve this, he says, harvesting must be done in a way that benefits the entire ecosystem, from those seeking extractive value, to the animals that call the forest home, to recreationists who use the lands for adventure.

A photograph taken in the Ataya, a 100,000-acre tract running along the Kentucky and Tennessee border near Cumberland Gap National Historical Park. (Photo Courtesy: The Nature Conservancy)

Rather than clear-cutting young forests when trees are just beginning to store carbon and help maintain the watershed, the land managers thin the forest, leaving the canopy intact. It’s a management plan that keeps more wood standing on the ground and thins the forest of trees that are showing signs of decay.

“Sustainable foresters take the sick, the weak, and the lame,” Zuckerman says. “They cut trees in the shade of others that would probably die in place. Think about a majestic old-growth forest with just 30 trees to the acre. When it started out, there were hundreds [of trees to the acre], but they died out over time. If a working forest is managed with ecoservices in mind, it can provide wood product and support carbon sequestration and water quality and wildlife habitat and recreation…”

Currently, both tracts of the project have established leases that allow for hunting and fishing. The Highlands tract in Virginia also has established ATV trails. And a portion of the 300-mile Cumberland Trail borders the eastern edge of the Ataya property. But Terry Cook, TNC’s state director for Tennessee, says the current recreation opportunities are just the beginning.

“Now that the acquisition is complete, we kick into a different phase of the project where we’re on the ground learning about the landscape and understanding the opportunities at hand,” he says. “There’s a lot for us to learn, but we’re not taking anything off the table. It’s a big enough landscape that you can accommodate a wide variety of uses, whether you like to bird or use an ATV. All those things can be integrated into a management plan that allows multiple users to access this property.”

Read more stewardship stories from the Co-op Journal.

Related articles: