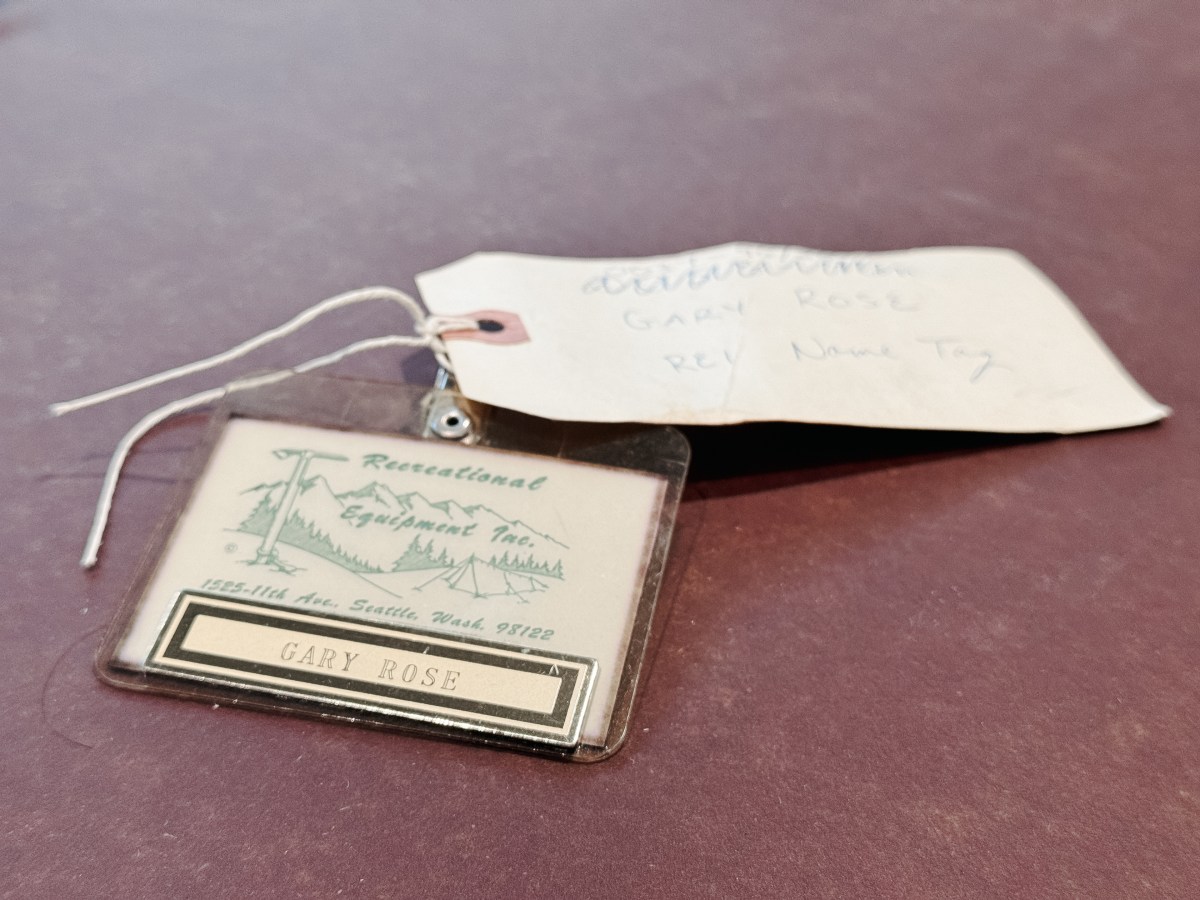

Gary Rose came into work the other day. This was unusual, considering he’s been retired from REI for nearly 30 years. He walked in with the slow but confident gait of a man who, though nearly 90 now, has been active his whole life. On a table lay pieces of gear, each bearing a tag with Rose’s name and the year they’d been bought as items for the co-op to sell:

A plastic canteen.

Children’s bentwood snowshoes.

Ancient ice screws.

An altimeter.

Rose was a major buyer for REI for decades, procuring items from all over the world. “Are any of these things that you sourced?” asked Will Dunn, REI historian and impact communications program manager, who had placed them out for Rose to see.

“Oh yeah,” Rose replied.

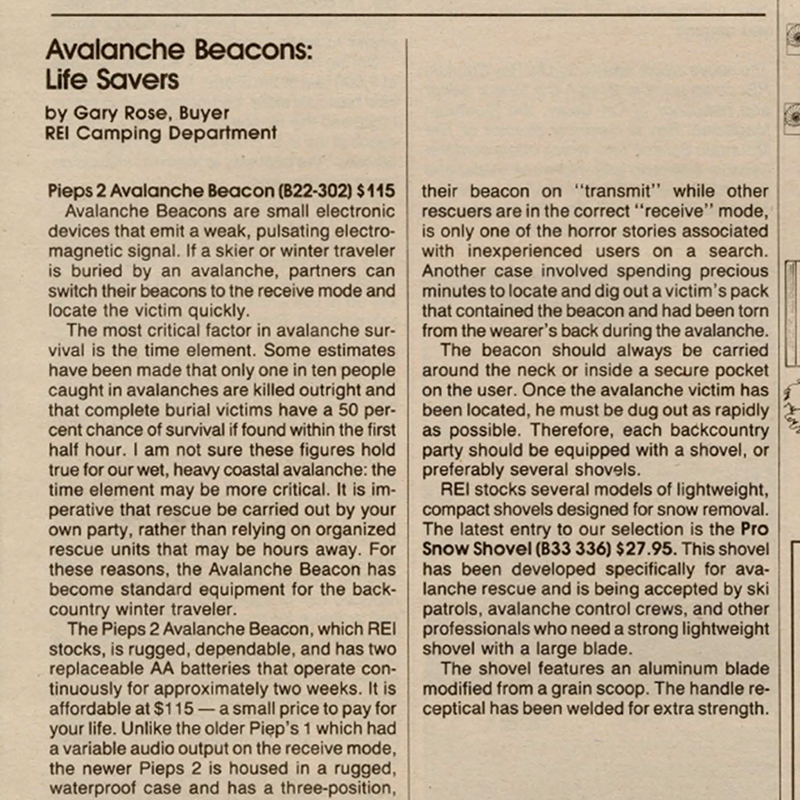

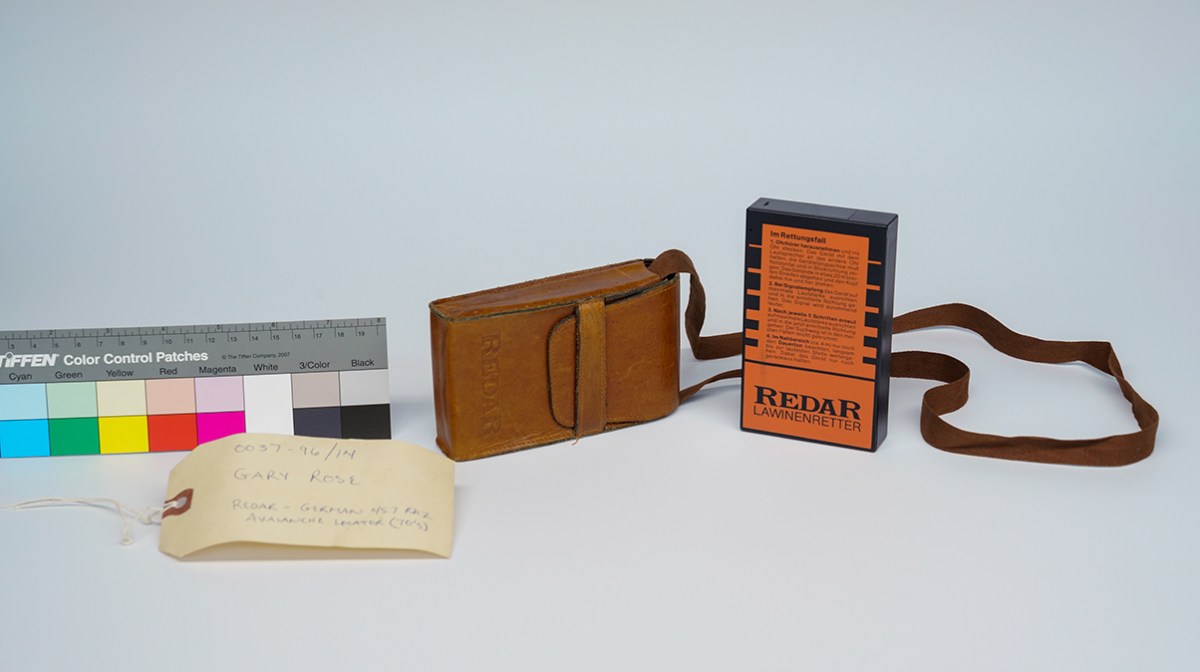

He picked them up in turn: Pitons. A Primus stove. Carabiners. Avalanche transceivers from the 1970s and ‘80s. The slide rule that Rose used before computers. His face took on the look one gives an old friend seen at a high school reunion after too many years—first recognition, then delight, as memories came back. He hadn’t laid eyes on the items in at least a quarter century.

Rose, who worked for REI from 1960 to 1996, is a living link to REI history, a key member of that second generation of leaders who learned at the feet of founders Lloyd and Mary Anderson and then carried forward the ideas and ideals of the co-op. Rose started as one of the co-op’s earliest employees before becoming a key buyer. As interest in outdoor recreation boomed starting in the early 1970s, his choices literally stocked the shelves and made REI an indispensable stop.

“If anyone ever deserved the designation of REI icon, it’s Gary Rose,” Mike Boshart, who worked for REI for several years and served briefly as Rose’s assistant in the mid-1980s, wrote in an email.

Rose was visiting the co-op’s new Creative Hub in Seattle’s SoDo district at Dunn’s invitation. Here, designers, prototypers, engineers and product testers collaborate on the future of REI Co-op products.

As he entered, Rose walked past a room filled with racks of colorful clothing—shirts and jackets for spring 2025—and another filled with mountain bike frames. Rose looked around him, amazed. In the middle of the Creative Hub sits the Living Archive, overseen by Dunn—an arrangement that clearly signals the desire that REI’s past continues to inform and enrich its future.

From the table, Rose lifted an ice axe with an aged ash shaft and a steel adze. He turned it with the appraising hands of a former mountain guide, happy to see his name stamped in the metal. (He’s climbed Mount Rainier 45 times, from seven routes.)

“Grivel.” He said the brand without needing to look. “A good quality one. But heavy. We’ve shortened ‘em up, too.”

Born and raised in Edmonds, Washington, he’d fallen hard for the mountains at age 15 while taking a climbing class from The Mountaineers, whose clubhouse was next door to a young REI. After graduating from the University of Washington, Rose became a summit guide on Mount Rainier. On his days off he returned to the Seattle area to run errands and wash clothes. He’d also often swing by REI to replace a piece of gear, and got to know Jim Whittaker, then the sales manager. Whittaker worked under co-founder Lloyd Anderson. (Whittaker, of course, went on to be the co-op’s second president and CEO.)

“I happened to be in there one time in the fall and I said, ‘Are you gonna have any openings for job opportunities?’ And [Jim] said, ‘Well, one of our salesmen is going back to school, so we’ll have an opening. If you’re interested, come on in.’”

“That was the first of October, 1960. And I spent the next 36 years there.”

What job did he do at first?

“Sweep the floor,” Rose replied and chuckled.

“You were just kind of a jack-of-all trades,” he said. “Sometimes I’d work on the cash register. Sometimes I’d help the customers; stock shelves.”

REI stocked mostly hard goods for climbing mountains at the time, along with dehydrated food and Sno-Seal for waterproofing. Back then, climbing ropes came in giant spools of Manila rope. The salespeople spent a lot of their time cutting coils of rope for members or making crevasse slings. Rose remembered their shortcut: If a customer wanted 150 feet of rope, they’d run the rope from the spool down to the end of the hall, to the maps, to the map of Chiwaukum Peak, and then double it back.

The store was located above the Green Apple Pie Café at 6th Avenue and Pike Street downtown and there was no freight elevator, Rose recalled. So “everything had to go up the stairs.” The co-op wholesaled Vibram® boot soles from Italy to cobblers around town. The heavy rubber soles arrived in massive wooden crates that had to be wrestled up the stairway. He laughed at the memory. “They were a gut-buster all right.”

Most of the time, though, “I loved working there,” Rose said. “You really got acquainted with the members. The same people came back in, back in, back in,” he said. “I made a lot of friends. … It was a close community of climbers.”

Rose’s career as a buyer happened nearly by accident not long after he started.

“Lloyd did most of the buying,” he said. “I went to him one time and I kind of shot my mouth off.” In his view, Lloyd always seemed to buy too much 16mm film. The leftovers would expire, Rose told him, and they’d have to throw it away. “I think it probably made Lloyd a little mad, kind of questioning him.

Because he said something like, ‘I don’t know anything about film. Why don’t you buy it from now on?’”

So Rose started buying the film. Pretty soon he was buying a lot more things, and then he was spending all his time buying instead of helping customers on the floor. His responsibilities grew to purchasing “whatever Lloyd didn’t buy.”

Rose doesn’t brag about his career; he credited his promotion not to his acumen but to the store’s booming business at the time. But there’s no doubt he became good at it. What neither man knew, then, was that moments like this were signs of the next generation of leaders starting to take the reins.

And between them, REI was sniffing out and importing transformative gear such as the Svea 123 camping stove, the first compact stove to use white gas. (The all-gold Svea roared like a jet engine in the woods; the late writer Harvey Manning called it “the Swedish hand grenade.

Rose was “protector of the soul of the company during years of dramatic change,” Boshart says. “A good reality check on what was actually practical to execute, Gary could be an understated but highly perceptive critic of new initiatives, especially if we started to get ahead of ourselves.”

In 1964, Rose traveled to Europe with Lloyd and Mary to seek out products. It was the first of many such trips. Rose remembered one in particular with Lloyd: The two rented a VW Beetle and drove from southern Italy to nearly the Arctic Circle in Sweden, visiting stove companies, shoemakers and tent manufacturers, and climbing along the way. One day they climbed Switzerland’s Jungfrau, descending too late to catch the last train down the mountain. They had to spend the night in the cog railway’s upper station.

By the early 1970s the outdoor industry was rapidly changing. The supplies of Army surplus gear that for decades filled shelves of the early co-op—the 5-cent tubes of sunscreen, the wool pants—were drying up. Meanwhile, the ‘60s, with their environmental awakening, were sending a new generation of Americans into the woods and mountains. REI almost couldn’t handle the amount of new customers, Rose recalled. Luckily, this meant a wave of new product innovation. That made the role of a savvy buyer more important than ever.

But was the stuff good enough for customers, who relied on it?

At the Creative Hub, Rose walked through a door. A sign overhead read, “We Test the Gear.” This is the Magnusson Test Lab, where since 1971 the co-op has put items—from sleeping bags to tent poles—through their paces to make sure they’d last.

Jim Hollenbeck, the Magnusson Lab Shop lead, showed Rose the computer-controlled hot plates, the tear-strength machines, the environmental chamber that can go from -85°F to 185°F.

Rose looked around.

“What an improvement,” he said. His voice held the wistfulness of the former buyer who wished he’d had such help in his day.

How did he and REI determine quality back in the 1960s? someone asked.

“We’d bend it—and break it if we could!” Rose replied, and he laughed.

“It’s kind of what we still do,” Hollenbeck replied.

Rose worked with Cal Magnusson, a legend within the co-op who ran product testing and whose name the lab now bears. Magnusson was brilliant and frugal and known sometimes to devise testing machines out of junkyard materials.

“I remember Cal made an abrasion tester for webbing and ropes,” said Rose. “He went to a junkyard and got an old crank case.”

“A Peugeot engine block,” confirmed Hollenbeck.

“I was down in the lab one day,” said Rose, “and I said, ‘Cal, if you’d only gotten a V-8 engine, you could have worked twice as fast!”

Gear quality did improve, Rose recalled. But, he said, “It didn’t happen overnight.”

By the mid-1970s Rose was responsible for bringing in a variety of products: batteries, instruments, packs and rucksacks, gear for water sports, tentpoles, pegs, stoves, snowshoes. “The biggest purchase order that I ever wrote was for over a million dollars’ worth of down” so that a supplier, Washington Quilt Company, could make sleeping bags for the REI label, he said. “They used to laugh at me and call me the Feather Merchant.”

There was a thrill to the hunt for the next useful item. What kind of gadgets could they buy to make the outdoor experience better for people? “If we didn’t have it, and you found it and ended up putting it on the shelf, you got satisfaction out of it.”

Consider the avalanche shovel: One that Rose had seen in Sweden didn’t impress him much; it was clunky and heavy. So he worked with a supplier in Bellevue, Washington, to create a folding shovel for REI. The finished product fit neatly on the side of a pack and the blade could tilt. “Boy, you could really move a lot of snow with it, if you were digging a cave, or digging a buried victim out of an avalanche,” he said. “They were quite popular.”

Not every idea worked out. “We had losers, that’s for sure,” he said (that chuckle, again).

For a time, REI sold insect repellent made of 100% DEET—about three times what’s considered necessary to deter biting insects and what most other brands contain. “It was really powerful stuff,” Rose said. “The mosquitoes, they wouldn’t even land.

“I remember we got a complaint one time. Some guy comes in; he’d bought a bottle of that and he’d left it on the dashboard of his car, and it ate the plastic off. I think it was an insurance claim. They had to buy him a new dashboard.”

Rose retired from REI in 1996. By that time, he was the camping buyer. “It was all the penny-nickel-dime items—whistles, you name it. Lapel pins,” he said in his typical understated way. Pressed, he acknowledged that “it was actually one of the biggest departments, for dollar sales, because they had so many different items.”

Says Boshart of his former mentor, “Gary knew just about everything in key areas, and was glad to openly share without making you feel stupid for asking…. When we moved to doing regional store tours and product clinics, employees hung on Gary’s every word.

“People still say with pride: ‘I worked with Rose.’”

By the time he retired, one of the biggest changes Rose noticed was how trendiness had entered the world of outdoor gear. “It seemed like what was hot last year, doesn’t sell this year. It was always jumping to something new.”

At the Creative Hub, it was time to go. Dunn told Rose he’d love to see that avalanche shovel sometime—he’d never heard of it—and perhaps take a picture of it for the Living Archive. And he invited Rose back anytime.

Rose picked up the ice axe one more time and smiled for the camera. Then he headed out into the afternoon sunshine.