It’s the end of September, and the air is thick with humidity. I’m not sure when, or if, I’ll return to Fire Island and run here again. Every routine feels unordinary. My hands fumble as I tie my shoes. I lose count of reps during my warm-up. It’s my last run here—in this magical place where I first learned to swim, ride a bike, break the rules—and I want it to count.

But as soon as I turn onto the dirt path that parallels the Atlantic, the wind picks up and I feel like I’m pushing my body through mud. My heart rate climbs as I struggle to keep my usual pace. My stomach clenches, and tears start to come. It’s not the difficulty so much as the knowledge that I can no longer push through the rough patches.

My family is selling the small, charmingly ramshackle New York vacation house we’ve inhabited—in both long- and short-term stints—since I was a little kid. I imagined this last run as my cinematic goodbye. It would be a kind of Rocky moment: proof that the training I’ve put in since May has made me strong, fast and reliable, like a machine. Instead, 3 miles in, I quit. The skies open and heavy rain follows. I don’t speed up or cower; I raise my face and rage, my cries swallowed by the wind. My body is not a machine.

What makes an honest effort? It took more than a year after my COVID-19 infection to be able to safely attempt running, and while I’ve made a fuller recovery than many “long-haulers ” (people who experience long-term symptoms from COVID-19), my body is different. I can’t risk ignoring the signals it sends.

Before I got sick, I ran on treadmills and sometimes on New York City streets where I cursed pedestrians and traffic for slowing my pace. I had little patience for these disruptions and the stop-and-start nature of my progress. I’d missed the crucial advice that the majority of one’s runs should “feel easy”—or rather, I’d seen the advice and ignored it out of a prideful refusal to put my body first. Eventually, an old injury would flare and I’d stop running completely until the whim struck me again.

I know now that an easy effort is typically one that feels relaxed and can be maintained for a long time: Breathing should be relatively effortless, and it should be possible to hold a conversation. According to certified run coach Elisabeth Scott, who’s behind the educational platform Running Explained, we can use metrics like pace, heart rate or power to determine easy efforts, but, she says, “At the end of the day, it only matters what it feels like.”

What feels easy day-to-day can change, due to a range of external and internal factors. Wind, humidity, heat, air quality and the terrain I run on can all affect difficulty. Sleep, stress and overall health play a part too. One way of explaining this variation is through allostatic load, “the cumulative burden of your stress and life events. … Everything that happens to you and how you deal with it,” Scott says. Because our level of stress changes frequently, what feels easy now won’t always be the same. In other words, “easy” isn’t a pace. It’s a feeling.

But since my hospitalization for COVID-19, not a lot has felt easy. Lasting symptoms of brain fog and exhaustion were accompanied by isolation and depression. A cascade of events followed: the loss of my grandparents, the end of my parents’ marriage, a cross-country move and financial instability. Through it all, I was coming to terms with a new identity as a chronically ill person.

External pressures can make it difficult for me to truly listen to my needs. When a faster runner passes me or a TikTok influencer pushes a training plan, it’s hard not to question my own approach. When I forgo a run because of other life stress or health issues, I feel guilty and inadequate. I’ve even worried about what fellow runners think when I’m not on my neighborhood route at my usual time.

“Mainstream fitness culture tends to prioritize going as hard and as fast as you can,” Scott explains. “That’s just not how you should be training … as an endurance runner or as a person.”

I spent the first year of the pandemic in my apartment in New York City, trying simultaneously to rest as much as possible, piece together an income and connect with others with long COVID. Many of those months were difficult; I craved sunlight and social time and grieved the loss of my pre-pandemic life. But I also learned more about my body. I discovered it was common for people with long COVID to experience exercise intolerance, and learned about post-exertional symptom exacerbation (PESE)—the worsening of symptoms after mental, physical or emotional exertion. Understanding PESE was vital for managing my symptoms and assessing my recovery. Knowing what a PESE “crash” felt like was crucial, because it would only be safe to experiment with minimal exercise once I was no longer experiencing regular PESE. To this day, I credit my fuller recovery to the time I spent resting and pacing myself during my initial months of illness—though I know economic privilege, luck and genetics likely played a part too.

In May 2021, I embarked on what would become a nine-month quest for a new quality of life that would ultimately take me to California, from the Bay Area down to Southern California. I wasn’t sure if this change should be permanent, but, as I told my partner, I didn’t want to stay put—spending every day searching for tiny beams of light in a city that felt less accessible every day.

My first stop was the small Fire Island cottage where I’d spent a large part of my childhood. In the beginning, my runs were short, slow and peppered with walking. I sometimes felt embarrassed when I passed people I knew or looked down at my phone to see my pace, so much slower than it was before my long COVID symptoms. But soon the salty breeze and dramatic sunsets eclipsed those preoccupations and deer that once irritated me appeared majestic. I ran alongside bunnies, feral cats and gulls, taking in the familiar with new eyes.

After an exhausting cross-country flight amid a wave of a new coronavirus variant, it took a while to settle into California life. When I finally did hit the road on my first run, I released all expectations, only to find myself flying effortlessly through the miles. I was once again engrossed in my surroundings: seabirds, houseboats and winding streets strewn with orange and red leaves.

In Joshua Tree a month later, I again reset my expectations. The whims of the desert dictated my runs. Coyote cackles told me when it was too late or too early to head out alone. Strong winds could make even a slow walk effortful. Deep stretches of sand tested my ankle and foot strength. Whenever I became miffed by the desert’s attempts to halt my progress, I’d reengage with the present. Looking up at the surrounding blue mountains, I felt a surprising confidence that I was where I needed to be.

I ran on empty roads and in crowded streets; in San Francisco fog and San Diego sunshine; wearing face masks during the omicron surge; passing long lines for COVID-19 testing; and exchanging thumbs-ups with other masked pedestrians. Running in such dramatically different environments kept me from prioritizing a particular pace. External factors that would have frustrated me before I got sick became challenges to handle with grace. I was no longer running in an internal landscape of numerical goals. I was running in the real world.

As my outdoor activity increased, I developed a greater awareness of the triggers that impact my symptoms. Humidity, heat and hills are limitations I don’t force myself to test. Not sleeping enough, not consuming enough sodium or not eating enough aren’t just inconveniences for me—they’re deal breakers. I craft careful schedules around my runs that include periods of rest before and after, and track my food and fluid intake carefully. I am proud to know my body, and these routines have given my life welcome structure during a time of enormous uncertainty. I appreciate the routine of my daily electrolyte-filled mocktails, Saturday night pasta and Sunday afternoon naps.

Still, sometimes I screw up. Early during my stay on Fire Island, I go for a run and, immediately afterwards, head to the beach, telling myself I can rest there. Once there, however, I can’t resist the water and dip. I’ve always been a strong ocean swimmer, but the conditions are rough and I fatigue quickly. I have to give everything I’ve got to get out safely. I collapse on my towel and try to catch my breath. An hour later, I am still woozy. I have to get home, but I can’t stand. I leave my belongings and crawl the block back to the house, pausing to lie in the shade several times. I spend the next 24 hours recovering. I also spend it scolding myself: I should really know better.

I’ve struggled to embrace the delicate line between understanding the positive impact of lifestyle interventions on my health and accepting that all interventions are not always possible. Even a perfect routine cannot guarantee wellness. I’m still working on greeting these moments with compassion rather than shame; I know I’m not alone in this.

In Meghan O’Rourke’s The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness—an investigation into the misunderstood world of “invisible” illness, including her own—the author expresses similar feelings after trying to reduce stress and eat differently. “You cannot muscle your way to health when you are chronically ill,” she writes. “Once you’re feeling OK-ish, trying to be the Best Patient in the World all the time can become an isolating preoccupation … the trick was to be a good-enough patient.”

Being sick, even when it feels preventable, is not always a lesson in doing better next time. I can’t hold anger at myself for not being able to better micromanage my life, or even for indulging in a joyous spurt of ill-advised activity.

In my personal experience, ableism, productivity culture, diet culture and financial instability have all affected my ability to give my body what it needs—both as a runner and a chronically ill person. When a choice has to be made between sleeping or finishing a contracted assignment to pay my bills, I struggle to prioritize my body’s needs—especially since I know financial instability could worsen my health in the long term. When my peers seem to be publishing stories rapidly, I find myself once again critiquing my pace. When I emerge from a symptom flare and pull on my running shorts to find that they’re fitting differently, the fluctuating shape of my body nags at me.

I fight these battles internally, and defeating these demons rarely results in external validation. No one wins a gold medal for dismantling their internalized ableism, but awards are often given to those who push through pain to meet public expectations. Even when people with disabilities are celebrated, it is often through a lens of “inspiration porn,” applauding an ability to appear “normal” or productive despite a disability. The scenes of my life where I’m honoring my health are often quiet, and sometimes boring. When I feel like I’ve failed at managing my health, I try to remember O’Rourke’s words: “The calamity here is not one of personal failure, but of social failure.”

“Even a perfect routine cannot guarantee wellness. I’m still working on greeting these moments with compassion, rather than shame; I know I’m not alone in this.“

By my first winter in California, I felt confident that I had a grasp on my body’s signals. Then, I got my first GPS running watch. Suddenly, I was presented with heart-rate, “load” and effort level data that led me to question what I perceived. If the run hadn’t felt easy, but the watch said it was, who should I believe?

For all the high-powered functionalities and algorithms, my GPS watch can’t track my frequent headaches, chronically scratchy throat or intermittent dizziness. It doesn’t register the stress that comes with moving across the country without a plan. Its sensors can’t pick up the brain fog and flu-like symptoms that come with my menstrual period or the grief and fear that still clutch at me. Only I know these components that make up my “effort.”

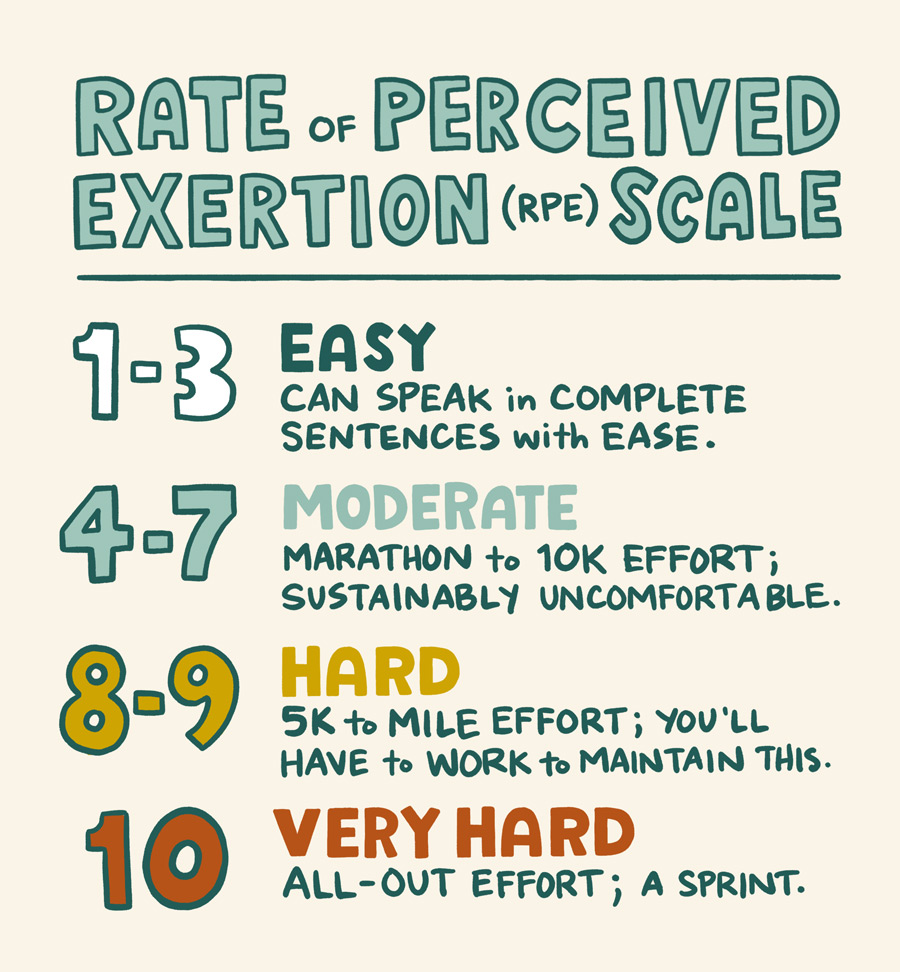

Because mainstream fitness culture (think HIIT, CrossFit, weight lifting and the like) rarely emphasizes “feeling,” instead prioritizing data and comparison, I was surprised to learn that the way we measure running efforts has long been tied to subjective perception. The Rate of Perceived Exertion scale, or RPE, measures the intensity of an effort on a scale of 1 to 10. It’s a subjective assessment of difficulty and depends on our ability as runners to honestly assess what we’re feeling. When I learned about the RPE, which has existed in some form since the 1960s, I was struck by how it empowers runners to be experts on our bodies. But the scale’s open-ended format is also precisely what’s tricky about it.

By spring, I have finally landed in a permanent home: a Los Angeles apartment with big windows and plenty of sunshine. I head to Elysian Park to see a friend I first met in a long COVID support group. Like me, Pato Hebert has spent the past two years learning how to live in a new body. He tells me about a project he worked on with writer Nishant Shah—an illustrated essay, which is an attempt to reimagine pain scales (the “objective” metric tool providers sometimes use to judge a patient’s pain). Hebert has painted watercolors that correspond to different types and experiences of pain. Deep red, green and yellow hues bleed, drip, scamper and crawl across the page. I see my own symptoms reflected in the shapes.

If effort is a feeling, our symptoms are, too. Many people who develop long COVID say the bone-crushing fatigue is impossible to impart to those who haven’t personally experienced it. While these symptoms have scientific bases for existing and are replicated in the experiences of millions, the widely varying feelings contained are often best understood through our subjective experiences.

Evaluating feelings can help in managing symptoms. Doing so also helped me discover easy-effort running as a way of honoring my body and getting outside, without overexerting myself. But the practice doesn’t have to preclude ambition: Easy-effort running is also one of the best ways to safely improve over time.

Scott says the average long-distance runner should be doing 80% of their runs at an easy effort, which is below your aerobic threshold. Building aerobic capacity and endurance is a foundational process that allows runners to become more efficient. Because easy efforts are less taxing on the body, running in an easy-effort zone can allow runners to build volume while avoiding burnout and injury. In turn, increased volume can improve a runner’s speed in the long term.

While I’m interested in getting stronger and faster, and it’s been exciting to build mileage slowly over time, I think about progress a little differently. I have yet to sign up for a race. Because my physical capacities vary from day to day, and it’s not wise for me to push past certain limits, I’ve avoided training for a single race day. Maybe this will change, but, for now, easy-effort running, without a goal, doesn’t bore me. It offers time to practice a kind of mindfulness I chased pre-pandemic, which ironically came more easily after I fell ill.

As I read more scientific literature on long COVID and related illnesses, I accept that the currently mild nature of my symptoms may not be permanent. Subsequent viral infections seem to worsen some people’s health. One provider tells me my symptoms may wax and wane throughout my life. This illness is not entirely new, but it is under-researched.

As I am engaging more with disability justice, I come across the idea that most nondisabled people are only temporarily nondisabled. This concept has its flaws, to be sure, but it can still be powerful; it has resonated with me in moments when I’ve wondered why I got sick so young. Facing disability head-on, rather than trying to ignore my health (or insisting this is temporary) has helped me recognize some of my own internalized ableism.

This is not to say I developed a mentality of pushing myself now because there’s no guaranteed later. Rather, I try not to take certain experiences—like running, seeing friends or having a clear enough mind to write—for granted. The knowledge I’ve gained from my illness sometimes helps me live more in the moment, every run becoming its own unique moment and memory, divorced from competition.

I still set goals sometimes, often motivated by the thrill of seeing more scenery in a single run. I imagine myself traversing the California coast or exploring the full length of Fire Island in one day, and sometimes these daydreams get the better of me—temporarily leading me to push harder in the service of my vision. Eventually, I recognize this mistake, give myself grace and attempt to return to the present.

This week I hope to log 20 miles for the first time, but there are no certainties and few expectations. Tomorrow is just another day I can’t predict.

Today, on my run in Griffith Park, a wooded haven in the middle of Los Angeles, I see a family of deer. They are beautiful—grazing and gracefully leaping across the field, ears perked to my arrival, reminding me of home. They are here and so am I. So, I stop, pause my watch and take a moment to be with them.