It’s one of the most controversial mainstays of the outdoor industry: synthetic apparel. Thanks to its breathability and sweat-wicking capabilities, everything from jackets to baselayers to pants and gloves often includes synthetic materials like polyester or nylon. But these technical fibers come with an environmental downside: They can take hundreds of years to degrade.

Thankfully, times are changing. Synthetic materials are still prevalent in the outdoor and fitness industries, but brands have started to chip away at their environmental impact. The latest collaboration between running company Janji and Cocona Labs offers one way forward. Launched last fall, Janji released a new run collection with Cocona Labs’ 37.5® Technology, a series of temperature-regulating fabrics, with a special focus on what happens to the items after they are discarded.

The end result is running apparel that, according to lab tests, degrades in mimicked landfill environments significantly faster—about 74% biodegradation in 726 days, as indicated by those lab tests—than average, according to the company. Time will tell if these benefits bear out in the real world. To date, REI also carries products by Trek and Fourlaps that also use this same 37.5® technology.

“It’s about circularity,” says Cocona Labs president Blair Kanis. “If you’re just focusing on the materials that are going into the product and not focusing on how they behave at end-of-life, you’re missing half of the story.”

What’s the Problem With Synthetic Fabrics?

Once upon a time, we weren’t reliant on synthetics, or materials that do not grow in nature like cotton, silk, flax or wool. Nylon, the first manmade fiber, was invented in 1938 by a chemist at DuPont Company. Scientists loved the durability with nylon since the previously used plant fibers (like cotton) didn’t have those characteristics. As a result, synthetic materials took the world by storm in the 1950s, gaining popularity thanks to the ubiquitous nylons that replaced pricey silk stockings.

Now, our reliance on synthetics has only grown thanks to the same benefits that brought them into the limelight over 70 years ago. Synthetic fabrics excel at wicking and dispersing sweat, so you stay dry during hikes, runs and other activities. They also don’t wrinkle, shrink or stain as much as cotton or other natural materials. Synthetics like spandex also provide stretch and movement, so you can engage your full range of motion while cycling and practicing yoga, for example. Even more, they’re affordable. On average, a synthetic shirt will cost a runner less than one that’s entirely made from a natural bacteria-fighting fiber, like merino wool.

It’s easy to understand why synthetic fibers rose to fame, but they have a considerable dark side. Unlike natural fibers, synthetics are made from petroleum, a fossil fuel, and they don’t degrade in landfills like natural fibers. While all fabrics shed fibers, synthetic materials shed microplastics, which are quickly becoming a global issue. It’s thought that a single synthetic running outfit can take anywhere from 20 to 200 years to fully decompose. When you add up all the apparel from around the globe, that’s a mountain of clothing piling up.

The Performance Benefits of 37.5® Technology

It started with a scientist in the sand. In 1992, a chemist and inventor traveled to Mount Aso in Japan where he dipped into the volcanic sand baths, a detoxifying treatment where hot sand is raked over your body. Theoretically, the heat and weight of the sand relieves musculoskeletal stiffness. At first, he assumed he’d only be able to hang for a few minutes until the hot sand scorched his skin. But once he dug himself a hole and buried his body, he realized he could stay in the cool sand beneath the surface for hours. This lightbulb moment was the origin of 37.5® Technology, aptly named for the ideal core temperature of -37.5°C and a relative next-to-skin humidity of 37.5%. 37.5® Technology and its materials claim to keep you comfortable within these parameters.

While everyone else was creating sweat-wicking fabrics—or spreading liquid sweat across the surface area of apparel so that it dries quicker—he realized that catching and removing the sweat vapor before it transformed into liquid was the key to regulating body temperatures to cool you when you’re hot or keep you warm when you’re cold.

“By removing humidity from your clothing, you stay cooler and dryer and you perform better,” Kanis says.

37.5® Technology took this concept and applied the technology to polyester and nylon yarns which aren’t that breathable on their own. Once a team of designers permanently embedded trace amounts of natural volcanic minerals into the yarn, they were able to create a fiber that’s similar to lava rock with its many porous holes. Not only does the application of these minerals increase the surface area of the fiber, but it also attracts and traps the moisture coming off your skin before it turns into liquid.

Good news, runners. This diffusion of water vapor creates a cooling effect that can help regulate your body temperature as you ramp up the miles.

Janji and 37.5® Technology: The Biodegradation Benefits

As years passed, the creators of 37.5® Technology wanted to move towards a more sustainable product. They knew that polyester nylon fibers took much longer to degrade so they decided to focus on what happens once that clothing was discarded, or the “end-of-life” factor. This is when they came up with Enhanced Biodegradation, an additive that could accelerate the breakdown of the synthetic fibers in the landfill.

Typically, municipal landfills operate with anaerobic conditions. This means that instead of oxygen decomposing the waste, methane-producing bacteria are doing the job. This lack of oxygen is why it takes so long for synthetic apparel to degrade. However, the Enhanced Biodegradation additive is accelerating that process, making it easier for microorganisms in the soil to secrete enzymes that break down synthetic fibers.

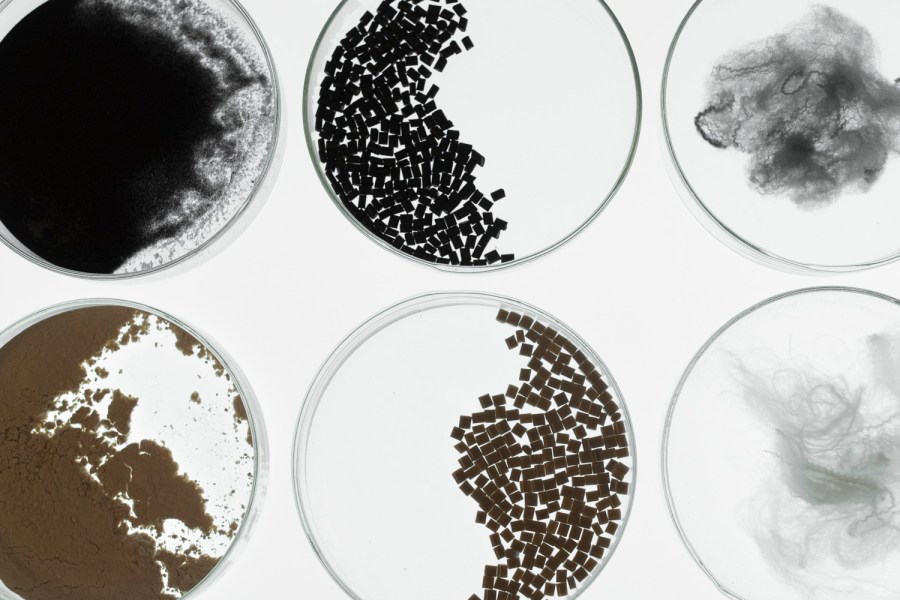

According to Kanis, it’s easiest to look at the science like a recipe. Synthetic fibers start out as pellets before going through extrusion, a process where something is pushed through a small space to create something new. In this case, the synthetic pellets go through extrusion and come out the other side as the yarn fibers. During this process, scientists can add various ingredients that become part of the inherent structure of the yarn. In this way, the Enhanced Biodegradation is not a coating or a chemical finish. Instead, it’s a permanent part of the synthetic yarn structure. (While Kanis can’t disclose the specific ingredients of the additive, she does say that it is starch-based.)

Kanis is quick to say that the technology is relatively new, so Cocona Labs hasn’t yet been able to conduct a real-world study to evaluate the outcome over decades. However, the company has conducted studies in a lab mimicking an accelerated landfill environment, and the results are notable.

According to those lab studies, the technology could “speed up the degradation process from centuries to decades,” she says.

Janji and 37.5® Technology: End Result

For Janji, incorporating 37.5® Technology and the Enhanced Biodegradation additive makes perfect sense. Running apparel is typically packed with synthetic fibers to help wick away sweat and add elasticity. With 37.5® Technology, Janji has access to a material that could help their high-performance product degrade at a much quicker rate.

Last fall, Janji announced two new products constructed with Enhanced Biodegradation: the Runterra Bio-Long Sleeved Shirt and Repeat Merino Tech Shirt. Each shirt boasts a different construction. The Runterra collection uses a 70% cotton/30% 37.5 polyester blend for a soft and comfortable shirt with ample performance capabilities. The Repeat Merino collection differs, using 47% merino wool, 15% nylon and 38% 37.5 nylon. Regardless of construction, both run collections are designed with cozy technical performance in mind—and emptier landfills.

“A big component is making sure there are systems in place that can take these materials at end-of-life and process them in a way that creates more circularity,” Kanis says. “It’s not super sexy, and I’m not saying we can just snap our fingers and the product can immediately degrade. It takes a while, but we’re definitely better than we would be without it.”