Winter is what many trail runners like to call “lottery season.” It’s the time of year when many of the most popular, in-demand trail races and ultramarathons announce which lucky runners will earn coveted spots in their events for the coming year. Most trail races are capped at just a few hundred runners (for comparison, the New York City marathon has 40,000 runners). This is generally due to land-management permit restrictions and the reality that singletrack trails are simply not conducive to large crowds.

The explosive growth in popularity of trail races in recent years, however, has created high demand for those limited spots. So what’s a runner to do when she doesn’t get in to the races of her choosing, but still wants to chase a competitive goal on trails?

Attempt to set an FKT, that’s what!

Catalan mountain runner Kilian Jornet set the FKT for a roundtrip ascent of the 14,692-foot Matterhorn in Switzerland in 2013, with a time of 2 hours, 52 minutes and 2 seconds. Photo courtesy of Summits of My Life.

FKT is shorthand for “Fastest Known Time”—essentially, a speed record on any given route. There is no formal race or event for these routes, which include everything from long-distance hiking trails to circumnavigations of lakes or mountains, to “up-and-down” times summiting an iconic peak or completing a linkup of multiple peaks. (See below for a few North American classic routes.)

In many ways, chasing FKTs is the ultimate egalitarian “sport.” There is no entry fee to participate, nor any permission necessary other than the usual recreation permits one might need for a hiking or backpacking trip. Anyone, at any time, on any day, can try to break a record and set a new FKT.

Alternating between running, hiking and kayaking, British runner Jez Bragg set a human-powered FKT on New Zealand’s 1,864-mile Te Araroa Trail in 53 days, 9 hours and 1 minute in 2013. Photo by Damiano Levanti, courtesy of The North Face.

Nor is there an official governing body. The closest thing is a message board begun by adventurer Peter Bakwin at fastestknowntime.proboards.com, which tracks FKT records and attempts all over the world. Runners trying to set FKTs can report their accomplishments (or failures) on the board, discuss others’ efforts or gather route beta.

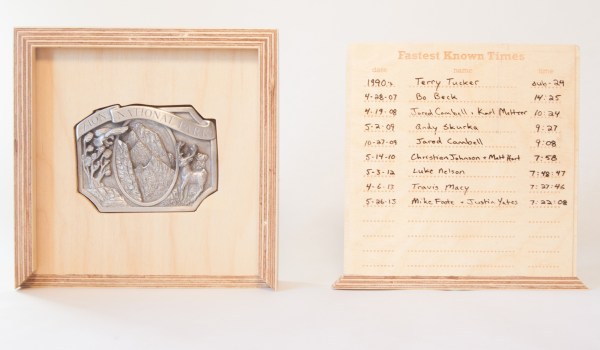

Just a couple months ago, mountain runner Rickey Gates began curating belt buckles—a customary finishers’ award for many 100-mile races—for a series of classic FKT routes, such as the Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim-to-Rim Crossing, the Zion Traverse, and the Mount Shasta Ascent. Each route has just a single buckle (or two—one for men and one for women) that’s a bit like the Stanley Cup of trail running; it lives with whomever possesses the current FKT.

Photo courtesy Rickey Gates.

FKTs are generally not verified in any way, but to ensure their accomplishments will be believed, many runners opt to carry satellite trackers on their journeys. Also encouraged are GPS devices, independent verification from witnesses, photos, videos and a detailed written record penned immediately upon completion—all geared at boosting the veracity of these feats.

As you might imagine, a do-it-yourself discipline that operates on the honor system leaves a lot up to interpretation and debate. Where does a route officially begin or finish? How much support from others is permissible? Can a runner be believed when he or she self-reports a new record? Should records be maintained separately for those who run a route alone, and those who do so as a team of two?

The debates, however, are lively ones, grounded more in camaraderie and curiosity than in hostility or rancor. At least thus far, the community of runners interested in FKTs has remained strongly committed to its tenets of honesty and respect.

In 2013, Jornet broke a 23-year-standing speed record by ascending and descending Europe’s highest peak, 15,781-foot Mont Blanc, in just under 5 hours. Photo courtesy of Summits of My Life.

FKTs are broken into categories of “supported,” “self-supported” and “unsupported.” Supported attempts allow a runner or pair of runners to utilize a support crew, who can provide water, food, a change of clothes or any other kind of gear supply along the way. Self-supported efforts (most similar to a traditional thru-hiking ethic) are not permitted a crew, but allow the runner to stash his own supplies along the route prior to the attempt. In an unsupported effort, no external support of any kind is permitted, other than collecting water from natural sources along the way; the runner must go alone and carry all her supplies from the start.

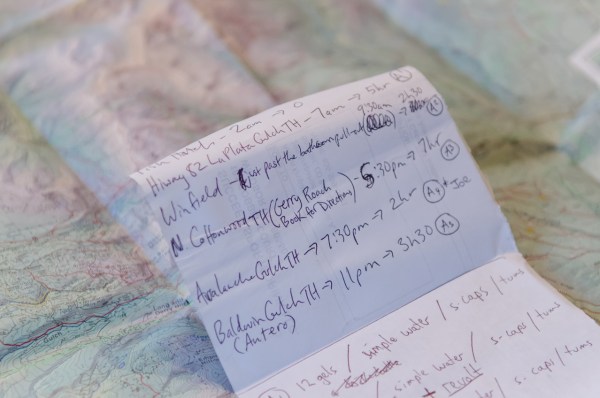

Runner Anton Krupicka’s notes and time projections while planning an FKT attempt on Colorado’s Nolan’s 14 route. Photo by Matt Trappe.

Runners may spend months poring over trail maps, planning their adventure, making projected time charts, then waiting for the right weather window to make an attempt. The longer the distance, the more likely attempts on it are to be supported. Many times, entire teams of friends or family mobilize themselves to support an FKT attempt—a sort of spectator-peloton devoted entirely to ensuring the success of one runner. They erect makeshift aid stations, replete with food and gear and other supplies, in the backs of vans or on the ground in trailhead parking lots.

Many friends rallied around Krissy Moehl to support her successful FKT bid on the Tahoe Rim Trail in September 2015. Photo by Fredrik Marmsater.

Records are maintained separately for men and women—though, on a number of notable long-distance trails, women have been known to set not only the women’s record, but the overall one as well. Heather Anderson, for example, set a new overall self-supported record last year on the Appalachian Trail, completing it in just over 54 days. Similarly, for four years, Jennifer Pharr Davis held the overall supported FKT on the Appalachian Trail (in 46 days, 11 hours, 20 minutes) before Scott Jurek broke her record in 2015 by a little over three hours. Pharr Davis retains the women’s supported record.

With new records set this past year on everything from the Appalachian Trail to New York’s Adirondack Great Range Traverse to Oregon’s Timberline Trail—and many covered in mainstream media like The New York Times—it looks as though FKTs have evolved beyond their origins as a niche-within-a-niche bit of whimsy in the trail-running community.

Four Classic Long-Distance FKT Routes in North America

Tahoe Rim Trail, California and Nevada

A 165-mile loop circumnavigating Lake Tahoe.

- Men’s Supported FKT: Kilian Jornet, 38 hours, 32 minutes, September 2009

- Women’s Supported FKT: Krissy Moehl, 47 hours, 29 minutes, September 2015

Accompanied by pacer Jenn Love, Krissy Moehl on her way to setting the Tahoe Rim Trail FKT in 2015. Photo by Fredrik Marmsater.

Colorado Trail, Colorado

A 486-mile trail from Denver to Durango.

- Men’s Supported FKT: Scott Jaime, 8 days, 7 hours, 40 minutes, August 2013

- Women’s Supported FKT: Betsy Kalmeyer, 9 days, 10 hours, 52 minutes, September 2003

Runner Scott Jaime on his successful FKT run of the Colorado Trail in 2013. Photo by Matt Trappe.

Wonderland Trail, Washington

A 93-mile loop circumnavigating Mount Rainier.

- Men’s Supported FKT: Gary Robbins, 18 hours, 52 minutes, July 2015

- Women’s Supported FKT: Jenn Shelton, 22 hours, 4 minutes, 47 seconds, August 2015

Runners Krissy Moehl and Darcy Piceu set and held the women’s supported FKT on the Wonderland Trail for more than two years before Jenn Shelton broke their record by about 18 minutes. Photo by Fredrik Marmsater.

John Muir Trail, California

A 223-mile trail from Whitney Portal to Happy Isles in Yosemite Valley.

- Men’s Supported FKT: Leor Pantilat, 3 days, 7 hours, 36 minutes, August 2014

- Women’s Supported FKT: Sue Johnston, 3 days, 20 hours, August 2009

Hal Koerner and Mike Wolfe set and held the John Muir Trail FKT for one year before Leor Pantilat broke their record by five hours. Photo by Tom Robertson, courtesy of The North Face.

Featured photo: In 2012, runners Matt Hart and Jared Campbell became the first people in 10 years to complete “Nolan’s 14,” a sub-60-hour linkup of 14 14,000+ foot peaks in Colorado’s Sawatch Range. Photo by Fredrik Marmsater.

Don’t forget to download the Trail Run Project Mobile App on iOS or Android to find your next great run.