As an undergrad at Santa Clara University, Mike Carey was a running back: He’d receive the football and rush through a sea of players that tried to shove or crush him. He couldn’t just look where he wanted to go, because that would telegraph his intentions to the opposing team and make it easier for them to anticipate his route and take him down. So, he relied on peripheral vision to find a path, which rarely followed a straight line. He had to leap and squiggle his way through the melee.

After college football, in January 1978, he turned his attention to downhill skiing. Crossing the parking lot at Palisade Tahoe in California, Carey didn’t focus on the storming snow or the beautiful woman who accompanied him (and who later said yes to his marriage proposal). Instead, his peripheral vision tuned in to the gravel scattered across the ground to improve traction. “I bet that really messes up people’s ski boots,” he mused. (Carey was right: Walking across gritty pavement could damage the underfoot anti-friction plates that bindings rely on for safety releases.)

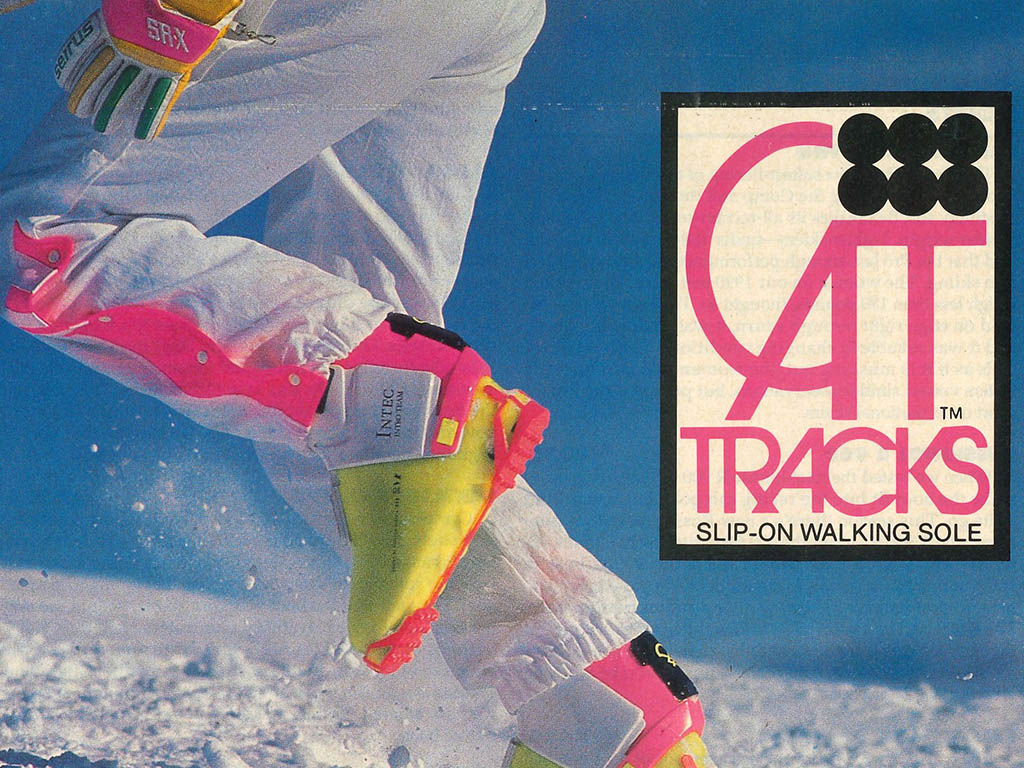

He hated skiing on that time out, but he still left inspired. Back at home, he cut up a rubber floor mat and crafted a clumsy sole protector made of wire and rivets. He used a thin layer of rubber with sticky “cleats” for traction and wire clips that slipped over ski boots’ front and rear to connect the toe and heel. A Santa Clara professor then helped him refine his Frankensteinian prototype into a production-worthy model made of injection-moldable polyurethane.

And just like that, Carey became an inventor.

Scientific thinking was routine dinner-table talk during Mike Carey’s childhood in Southern California. His father was a physician and his mother a nurse. (Her dad had been a doctor, too.) So Carey grew up learning about observation and analysis. “My mind has always wondered, ‘What if?’” he says. But his parents nipped any precociousness by teaching him that smarts don’t make you superior: People have equal value regardless of what they do. That humanistic philosophy would later steer his management style at Seirus and inform his “crowdsourced” approach to innovation.

When Carey wasn’t tinkering, he was a body in motion. He danced with the neighbor kids, ran on the track team, boxed and played basketball and football (his favorite). He studied biology in college, but business seemed like a more engaging way to satisfy his “what if” wonderings. So once he honed the ski-boot overshoes that he named Cat Tracks, he in 1979 launched a company called Winter Mountain with his new wife, Wendy. Together, they started selling accessories for skiing (including a “Fanny Flasque” that predated the rise of hydration bladders).

Ski boot and binding developers immediately endorsed their Cat Tracks, which the company says saw doubled sales every year for the first five years. It helped that in the early ’80s there were few accessories for skiing, so shops were glad to display a lower-priced item like the Cat Tracks. (And skiers seemed eager to gobble up items that made the sport more comfortable.)

Soon, Carey met another entrepreneur who was also pioneering winter accessories. In 1984, he joined forces with Joe Edwards, who had patented a neoprene face mask for skiing in cold weather. The duo formed Seirus. Carey’s first mission with the merged company was to improve neoprene’s next-to-skin comfort. He laminated synthetic fleece to neoprene, so it felt softer on the face, and from there, the company introduced an array of cozy accessories for the head, neck and face. The Neofleece Combo Scarf (which combined face and neck coverage) retailed for $19.99 when it debuted in 1991, when most accessories sold for much less. But sales spiked, more than quadrupling into the second year, and continued to increase significantly for the next six years. It launched Seirus into prominence.

Heated gloves came next. Seirus spent 10 years developing battery-powered systems that could warm skiers’ fingertips. The company tested various wiring designs and ceramic fibers before it launched heated gloves in fall 2012. Two or three other brands also launched heated gloves that same year, Carey recalls. But Carey believes that none had devoted as much time to the development phase as Seirus; the company had experienced failures with wires so innovated flexible heat panels instead.

Seirus, based near San Diego, now holds several patents. Its product line has grown to include base layers and liner gloves as well as neck gaiters and face protection. Its most recent patent, secured in April 2019, features a convertible balaclava with embedded magnets that allow the wearer to instantly attach a facemask to the hood.

But Carey learned early on that success is a team endeavor, and he rarely claims credit for the brand’s inventions.

Innovation at Seirus is a team sport. As the company’s President and CEO, Carey isn’t solely responsible for generating novel ideas. Neither is Bob Murphy, who joined the company shortly after Seirus was established and now heads up research and development as vice president of operations. Even Carey’s daughter Danica, who is the company’s director of marketing operations, sees innovation as a collaborative effort.

That’s because early on Carey established a steering committee to brainstorm new developments. Consisting of about 12 key sales reps, buyers and members of Seirus’s internal staff, the committee meets four times a year to discuss problems—not products. “Invention comes from a problem,” Carey says. Thus, the steering committee analyzes the pain points that skiers typically experience and offers “what if” ideas for addressing those issues.

“The reverence is for what comes next, not who finds what,” Carey explains. “So, it’s important that the collaborators feel they’ve got equal stature.”

Collective innovation is often ridiculed for generating weird or off-target products. (“A camel is a horse designed by committee,” sneered Alec Issigonis, who created the bestselling Mini automobile.) But Carey insists that diverse viewpoints only enrich the “what if” stage of design and that later phases of product development can rely on company leaders with experience picking winners. “It does take a discerning mind to determine whether you’ve got a thoroughbred or a camel,” Carey says. But he maintains that small, carefully selected committees play an important role in designing products that appeal to more than just their creator.

Now, Carey’s daughter Danica contributes to product creation, after a childhood spent filing company papers and hanging out at the office after school. She recently targeted the problem of keeping face protection sealed underneath a skier’s goggles. “I was constantly readjusting and trying to keep that seal from rupturing,” explains Danica, who is a dedicated skier like the rest of her family. She talked out her idea during a chairlift ride with Carey. Then she worked with a Seirus seamstress to develop a prototype for a face mask that attaches to a neck gaiter using a magnetic seam. Then Danica presented it to the steering committee and watched as her brainchild moved through the company’s latest patent-earning process.

“It’s a really hard thing, because in my mind, I came up with this,” Danica admits. Her name appears on the patent for the Magnemask, but its development into a viable product came from multiple players.

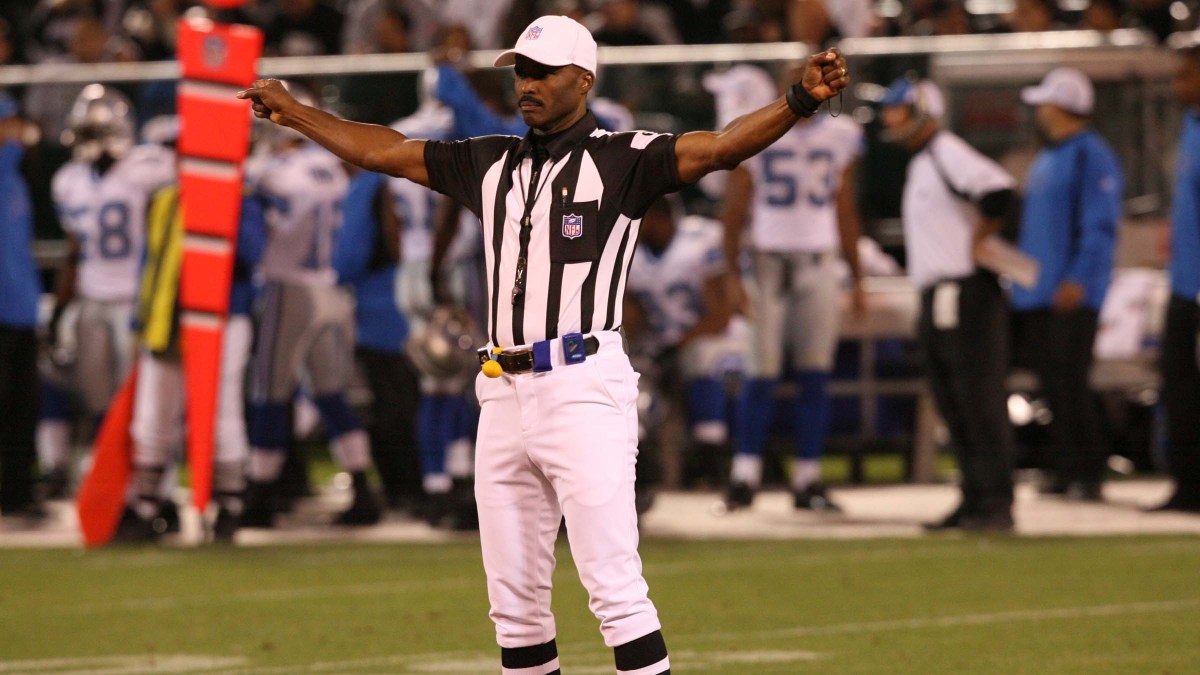

That’s a lot like what’s expected in football, Carey observes. “All those team sports rely on you sharing your participation and accolades with somebody else,” he explains.

His football involvement extended far longer than his college career. Carey worked for 24 years as an NFL official, first as a side judge and later as a head referee. (He was the first Black official to call a Super Bowl in 2008.) He retired from the league in 2013 and worked for two seasons as an NFL rules analyst for CBS.

Over a long career, he served on the boards of several organizations like the Boys & Girls Clubs of San Diego; and he was past board chairman of Snowsports Industries America, a trade association for the winter sports industry. (His wife Wendy is the group’s current board chairperson.)

Carey has also stepped back from day-to-day operations at Seirus. Although he looks all of 50, he’s 72 years old. And he’s accustomed to fielding questions about his fountain of youth.

“I walk every day and stretch every day, and I drink plenty of water,” says Carey, explaining how hydration was his father’s prescription for optimal health. Thus, basic habits can achieve grand results—from staying young to creating new gear.

Mike Carey has been an REI Co-op Member since 1988.