In August 2018, two of the world’s best skiers met for a drink in Portillo, Chile. Cody Townsend had an idea that he wanted to get Chris Davenport’s opinion on. He was considering trying to ski every line in the seminal coffee-table book, Fifty Classic Ski Descents of North America, which Davenport coauthored in 2010. No one has skied all 50 lines, and Townsend wondered: Could he ski all the lines? If so, how long would it take? What were the cruxes?

Davenport, who’s now 48, had watched 36-year-old Townsend’s career evolve from cliff-hucking freerider to one of the most well-rounded skiers in the sport—not unlike Davenport’s own path. In fact, 12 years earlier, after Davenport finished skiing all 54 of Colorado’s 14,000-foot peaks in a year, a mutual sponsor sent Townsend on the road with Davenport for a fall speaking tour at REI stores around the country. Davenport mentored the then 23-year-old, and they became friends. So when Townsend approached Davenport in Chile for advice, the former world champion freeskier knew exactly who he was advising.

“I told Cody, ‘Absolutely, this is possible. You have the skills to ski every one of these,’” Davenport recalled. Townsend may have the skills, but having the right conditions was another hurdle. Some of the lines, like Alaska’s University Peak, have been skied only rarely. It would be a feat of skill, luck and good timing to pull all of these lines off.

Emboldened by Davenport’s confidence, Townsend announced his project last fall and went on to ski 20 of the 50 lines over the course of last season—well on track to hit his goal to finish in three years. To document the project, Townsend—whose famous 2014 ski descent of a mesmerizing Alaskan cleft called the Crack got nearly 12 million views—is producing a YouTube series to chronicle his journey. Episodes of “The Fifty,” which began releasing online for this season in mid-October, typically receive between 40,000 and 60,000 views.

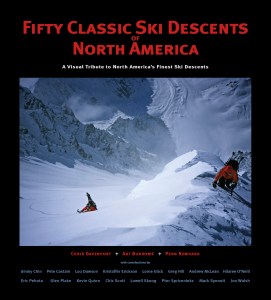

The Fifty Classic Ski Descents of North America was published in 2010—and recently got a spike in sales.

Thanks almost entirely to that attention, a funny thing has happened since the project’s launch: Sales of the Fifty book, which had grown more or less stagnant in the decade since it was published, have increased tenfold compared to recent years. “We were selling a hundred or two hundred a year,” Davenport said. “It was slow. But with Cody’s announcement, it just spiked like crazy.”

The poetic irony, of course, is that without the book, Townsend wouldn’t have a project. Davenport and his coauthors, fellow Aspen, Colorado, skiers Penn Newhard and Art Burrows, originally modeled the book after another cult-classic tome: Fifty Classic Climbs of North America, published in 1979 by Steve Roper and Allen Steck. The Aspen trio contacted ski mountaineer friends in every region of the continent to get ideas for the classics.

“We wanted to have easy, everyday routes, like the Silver Couloir on Buffalo Mountain, and we also wanted ones that are incredibly aspirational,” said Davenport, who has skied 21 of the 50 lines in the book. “But they all had to qualify under the standard of beauty. Aesthetics were the guiding light for this book.”

The book includes iconic lines like the Grand Teton in Wyoming, Mount Rainier in Washington, Tuckerman Ravine in New Hampshire and Mount Shasta in California, all of which get skied regularly. But it also includes rarer and much harder to ski descents like the north face of Canada’s Mount Robson, which has only been skied twice.

Filmer Bjarne Salén shoots for Cody Townsend’s ‘The Fifty’ YouTube series, atop Mount Shasta last spring.

Townsend remembers leafing through the book when it first came out and being surprised to see himself pictured skiing one of the lines (Terminal Cancer Couloir in Nevada’s Ruby Mountains). At the time, he despised sweating up the ascent and had little technical climbing experience. He quickly forgot about the book, but as his skill set grew, so did his interest in ski mountaineering.

“I had slept in a tent in the snow for the first time, used an ice axe and crampons for the first time and actually started to not hate the uphill as much as I used to,” Townsend said. “So suddenly, that next opening of the dusty book on my shelf had some meaning, and the lines began to jump off the pages and into my brain.”

Unbeknownst to Townsend, another skier, Noah Howell from Utah, had quietly launched his own pursuit of the same goal years earlier. Howell skied his first Fifty Classics line nearly a decade before the book’s release and has since added 29 more, including five last season. But Howell said he only hopes to finish in his lifetime, not necessarily before Townsend. And he’s doing much less to publicize his effort.

Davenport, Newhard and Burrows originally printed 10,000 copies of their book and had sold about 7,000 before last winter, when they sold another 1,000. That leaves around 2,000 copies of the book left. Burrows, a telemark-skiing pioneer who skied his first line in the book in 1977, said there’s no plan for another print run—unless Townsend’s project keeps spiking sales. As for Townsend, he said he has an open itinerary this winter, content to follow snow stability and try to ski as many lines as possible.

“Honestly, it’s beneficial for the video project to have sales of the book take off,” he said, “because it creates more investment in the journey.”