He didn’t invent snowboarding, but Jake Burton Carpenter, who died at the age of 65 on November 20 in Burlington, Vermont, probably did more to advance the sport than any other human. Last week, as news of his death spread, the snowsports community celebrated Carpenter’s life with tributes spanning the full range of emotions.

Some expressed adulation: “Outside of my parents, there’s not another person that impacted my life more than Jake,” wrote former Burton team rider Keir Dillon on Instagram. Others used humor to display their affection: “If it wasn’t for this dude, I’d be a skier,” remarked one Twitter fan. More than anything, those who knew him showed respect: “He’s … an incredible man and I’m honored to call him my friend,” wrote three-time gold medalist Shaun White, snowboarding’s most prolific star, on Instagram.

Carpenter launched Burton Snowboards in 1977, when there wasn’t a commonly accepted name for the popular activity we now call snowboarding. The industry flourished over the next 40-plus years, in large part thanks to Carpenter, who helped grow the sector to just over 2 million participants or approximately 4 percent of the population by 2017, according to the Outdoor Industry Association.

“If he met you for the first time he would give you a hug,” said Kimmy Fasani, a professional snowboarder and Burton team rider who earned her first Burton sponsorship in 1999 as a 15-year-old slopestyle champion. “For someone that had been the head of this huge company, he never made you feel like he was greater than you. He always made you feel like you were part of the family,” she said.

Born in 1954 in Manhattan, Carpenter started out on skis, but bought a snow-sliding device called a Snurfer when he was 14. The new toy ignited an unbridled snow-derived ecstasy, one that he would go on to eventually share with millions of participants.

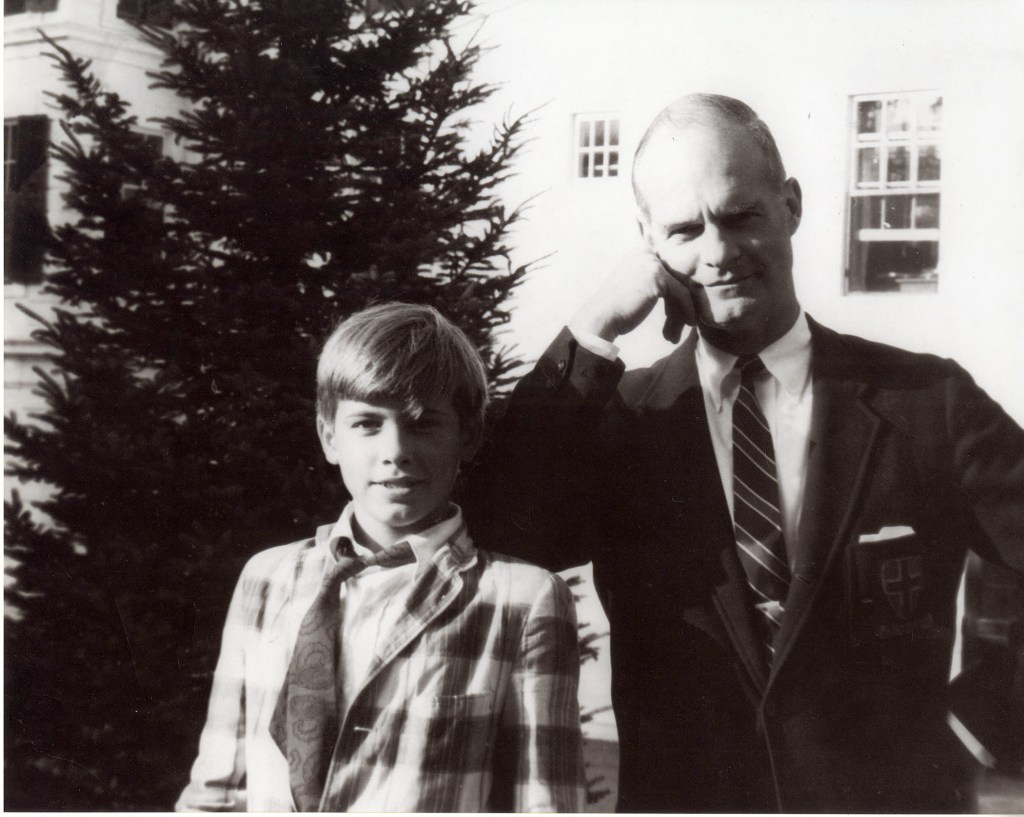

Carpenter at his elementary school graduation. Only a few years later, the budding athlete would discover the Snurfer, a predecessor to the snowboard. (Photo Courtesy: Burton)

The Snurfer—a short and narrow board with no edges—left much to be desired, so Carpenter got to thinking there had to be a better design.

He officially founded Burton in 1977, as a 23-year-old bartender, after a brief stint at a Manhattan investment bank. He worked out of a barn in Londonderry, Vermont, where he tinkered endlessly with materials, shapes and construction patterns, looking for the right design.

But even as his board designs progressed, snowboards were banned from most ski resorts, and the ski establishment saw the young boarding crowd as a set of rule-shirking renegades.

No one wanted to buy the boards at first. Carpenter sold a mere 300 snowboards in 1979, according to Patricia Outdit’s 2007 book Snowboarding, racking up thousands of dollars of debt. He described an early sales trip in a 2017 NPR interview: “I remember once, going out with 38 snowboards, and I drove around New York state and visited dealers, and I came home with 40 snowboards, because one guy had given me two back that he’d bought and said, ‘This is a joke.’”

He also lived through family tragedy, which taught him hard but valuable lessons. When he was 12, his older brother was killed in Vietnam, and five years after that his mother succumbed to leukemia. “The losses made for two things,” said Carpenter in a 1997 Sports Illustrated magazine article. “Real independence and an ability to persevere.”

A young Jake and Donna Carpenter in Stratton, Vermont, in 1990. Even as a business icon, Carpenter was a rider first. (Photo Courtesy: Burton)

With those hardened character traits as a pillar of Carpenter’s work ethic, the brand, and the sport of snowboarding along with it, started to move. By 1990, the majority of ski resorts allowed snowboards, although a few holdouts remain to this day.

Burton’s sales began to skyrocket. The company grew at a rate of 100 percent a year from the late ’80s into the ’90s, according to the 2009 book Battleground Sports by Michael Atkinson. Then snowboarding debuted in the Nagano Winter Games in 1998, and not long after, Shaun White, a wiry redheaded kid with a Burton board strapped to his feet, became the sport’s most globally recognized figure. By the new millennium, snowboarders were the cool kids in town.

The ultimate irony, and one Carpenter had a major hand in, is that the sport once shunned by the snowsports industry went on to help save it. Between 1988 and 1997, snowboard sales rose by 77 percent, while ski sales fell by 25 percent during the same period, according to the National Sporting Goods Association.

The ultimate irony, and one Carpenter had a major hand in, is that the sport once shunned by the snowsports industry went on to help save it.

“What snowboarding and Burton did is we revolutionized winter life,” said Carpenter in 2017. Burton also weathered the financial crisis of 2008, and the alleged decline of snowboarding that came in the middle of the next decade.

Through it all, Carpenter kept snowboarding and continued working. He rode up to 100 days a year most seasons, often with his three sons (ages 23, 26 and 30). Even as business icon, he was a rider first.

That sentiment also was reflected in how he treated Burton team members. Fasani, who became a mom in 2018, praised Jake and his wife, Donna, for working out a contract that kept Fasani on the team, which allowed her to take her son on many trips. “This is the most standout thing for me, what they did as a brand to stand by me as a female on their team,” Fasani said.

Carpenter reportedly hated wearing suits to work, and he maintained a strict rule that allowed employees at the Burton headquarters in Burlington, Vermont, to skip work if more than 18 inches of snow had fallen the night before.

He left a lasting impact on everyone he met, including REI’s vice president of merchandising, Susan Viscon, who was inspired by how the company, “put the power of their influence and impact to make the snowboarding world better, developing and investing in programs like Burton Learn to Ride, to get youth and families into the sport. They built women’s leadership programs that elevate representation of women in the industry, and established the Chill Foundation, which promotes building self-esteem in youth,” she said.

Carpenter slices through fresh snow in Stowe, Vermont, in 2007. (Photo Credit: Johannes Kroemer/Getty Images)

His health issues began in the early part of this decade. Carpenter was first diagnosed with testicular cancer in 2011 and underwent successful treatment, after which he sent an email to the company that the cancer was “toast.” Then, in 2015 he battled a rare nerve disorder called Miller Fisher syndrome, which left him paralyzed for eight weeks in the hospital. He slowly recovered, despite facing extreme lows.

Donna took over as CEO of Burton in 2016, with Jake remaining highly involved in the company, and even returning to the slopes in December 2015. But in early November 2019, the testicular cancer came back. He announced the news to his staff via email, and 11 days later, he died at 65.

To carry on Carpenter’s legacy, Fasani has a plan. “The biggest thing is to keep snowboarding, keep getting out in the mountains, keep progressing, and keep creating, as individuals,” she said. “Because that’s what life is about, and that’s how he lived his life.”