One year after the death of Squaw Valley ski patroller Joe Zuiches, his wife, Mikki, tries to make sense of it all.

Exactly one year ago, Joe Zuiches kissed his half-sleeping wife, Mikki, on the forehead as he left his house in the dark, at 3:30 in the morning on Jan. 24, 2017. Joe was on his way to his job as a ski patroller at Squaw Valley in California. He’d once read that you live longer if you kiss your spouse before you leave the house each day, so he always made a point to do so.

Later that morning, as a golden sun was rising over a brilliant blue sky—after days on end of pounding storms and feet upon feet of snow—Joe texted Mikki to say, “Another patroller blew his knee out, so I’m the supervisor.” He was doing avalanche control work to ready the snow-drenched mountain for the day’s onslaught of skiers and riders.

She responded, “Be safe.”

Mikki Zuiches holding a picture of her family at her home in Truckee, Calif.

Mikki dropped their 10-month-old son, Cannon, at day care, then went to work as an occupational therapist at the hospital in Truckee, where they lived. She was doing her morning rounds when a coworker mentioned, “Did you hear there’s been a fatality at Squaw?” Mikki froze. It couldn’t be Joe. There’s no way. Joe was the most safety-conscious man she knew, a Rainier mountain guide and veteran ski patroller with a careful, calculated approach to everything he did. His fellow guides called him Bull Moose, for being a quiet, thoughtful leader known for smart decision-making.

But just in case, Mikki pulled out her phone and texted her husband of three years. At 9:44 a.m., she wrote, “You OK, baby?” The text didn’t go through. Mikki knew something was wrong, but it took a while for the call to come through to confirm her worst nightmare.

Squaw Valley CEO Andy Wirth dialed her cellphone and told her that Joe had died at 8:35 that morning, while conducting avalanche control work on the ski area’s Gold Coast Ridge, a routine he had done countless times before. According to a statement later issued by Squaw Valley and based on an investigation from the Placer County Sheriff’s Office, Joe was killed in an incident involving a detonated, hand-charged avalanche explosive. With no witnesses and little evidence, the exact details of what happened still remain unclear.

The next few hours, days and weeks were a total haze. Mikki hugged her baby close, flew home to her native Canada and relied on the love, support and kindness of friends, family and total strangers.

Joe Zuiches died tragically and too soon, at the age of 42, survived by his beloved wife and infant son. But that is not his whole story. This is the story of a love that ran so deeply, so intensely, that even in Joe’s absence, that love still carries his wife and child through each day.

—

Mikki and Joe met in 2012 on the flanks of California’s Mount Shasta. Joe, a ski patroller living in Colorado, was working as a mountain guide with Shasta Mountain Guides for the summer. Mikki, who lived in Vancouver, B.C., was visiting a friend. Their second day together, they climbed Shasta in a matter of hours.

“He wasn’t a mountain guide who wanted to talk about his accomplishments,” Mikki remembers. “He wanted to talk about religion and philosophy. He was just so smart.”

Mikki and Joe on Mount Shasta, where they met and got engaged. (Photo Courtesy: Mikki Zuiches)

Joe was the kind of guy who kept long journals, spiral notebooks with scribbled pencil, where he tried to figure out some of life’s grandest questions. Why are we here? What is our purpose? “Joe would tell me that his favorite part of guiding was that he could think for hours,” Mikki says. “He was quiet but certain.”

Later, she learned that he told friends the week they met, “That’s the girl I’m going to marry.” The next time they met, they climbed Mount Rainier. They embarked on a long-distance relationship. A year later, back at base camp on Mount Shasta, he asked her to marry him. They wed in Washington in April 2014, honeymooned on Mount Shasta and she moved to Truckee, near the shores of Lake Tahoe, where Joe had recently gotten a new job as a ski patroller on the famed steeps of Squaw Valley.

A year later, Mikki found out she was pregnant. “Joe had never been more sure of anything,” she says. When she was eight months pregnant, they spent their babymoon on Mount Shasta, hiking to 10,000 feet with her swollen belly. Their baby boy was born in March 2016, and they spent the following summer living near Mount Rainier, while Joe guided during Mikki’s maternity leave.

Back home in Tahoe that fall, when Cannon was around 6 months old, they did their best to continue living their adventure-filled lives with baby in tow. They carried him in a backpack while they hiked through the woods, took him camping and brought him to the crag while they climbed.

At home, Joe would toss the baby books aside and read Cannon books about quantum psychics. He would rush home from work every evening at 5:30 p.m., strap Cannon to his chest and take him out for a walk—just the two of them, snow or shine. He would talk to his son extensively on those walks—telling him about his day, pointing out the trees and the sky. “When they’d come back, they’d both have this huge smile on their faces,” Mikki says.

Cannon has his dad’s smile, too: a huge, cheek-to-cheek grin that lights up a room.

—

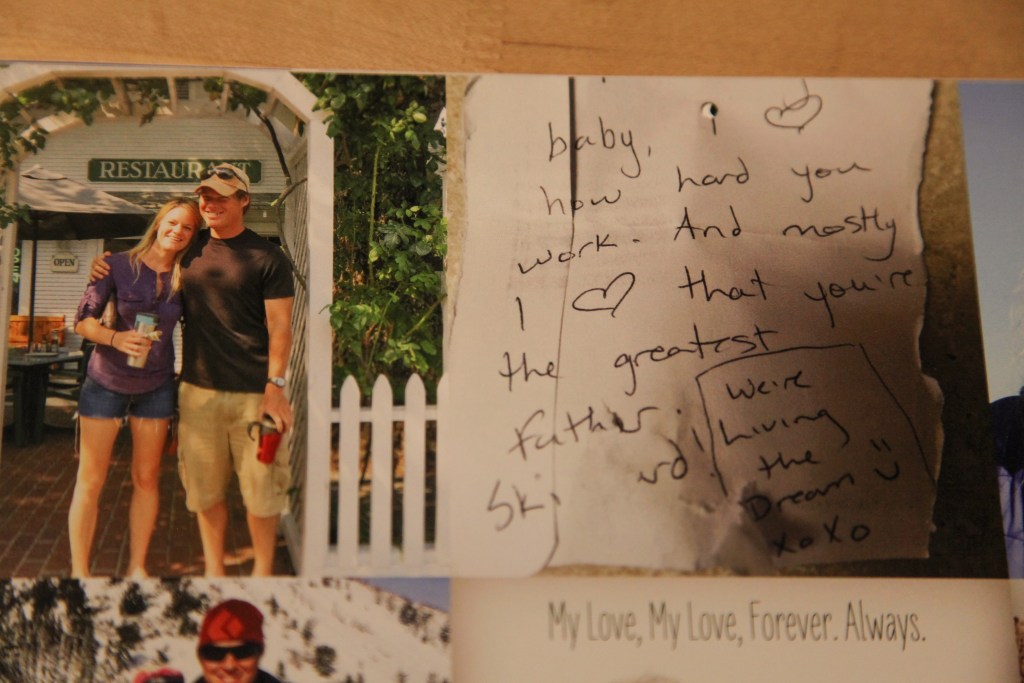

The night before he died, Mikki wrote Joe a note on a piece of scrap paper and slipped it into his lunch bag. It was the first time she’d ever done that. The note read, “Baby, I love how hard you work. And mostly, I love that you’re the greatest father. Ski hard. We’re living the dream.”

A copy of the note Mikki left in her husband’s lunch bag the day he died.

“I know that the day he died there was nothing left unsaid,” Mikki says. “I just hold onto that. I know he couldn’t have been happier.”

Now, one year after his death, Mikki says the hardest time of day is 5:30 p.m., when she looks at her front door and waits for Joe to burst in, give her a kiss and swoop their son out for a walk. Her eyes flood with tears as she thinks about it, but, she says, “I like to think that Joe shared what he needed to share with Cannon before he left, during those walks. I like to think that he got it all out. But there’s no 5:30 now.”

The support from her community continues to pour in: dinners delivered to her kitchen, an online fundraiser that raised enough money to put a down payment on a house, and friends constantly calling and checking in. This past Christmas, a group of friends arrived at her house toting a tree, decorations and a pot of hot cider for the stove. “Time doesn’t heal, but those acts of kindness heal,” she says.

When Mikki puts her son to bed now, she tells him stories of his dad. They usually take place on a mountain somewhere, sometimes involving a magical unicorn. (“We had a thing about unicorns, Joe and I,” Mikki says.) She reminds her son, every night, that his dad loved him very much. A heart-shaped locket around her neck holds a picture of Joe, and when they talk about him, Cannon, now almost 2, reaches for the necklace.

“I miss his energy,” she says about Joe. “He taught me to love in a way that I never thought possible.”

Mikki Zuiches at home, one year after her husband’s death.

In January, Squaw Valley ski patrollers hung a handmade, metal plaque on the ridge where Joe died. The perch overlooks the mountain, with views of Lake Tahoe in one direction and vast, rugged wilderness sprawling from the Pacific Crest in the other. The plaque gives tribute to Joe, names Mikki and Cannon, and includes a John Muir quote that reads: “As long as I live, I��ll hear waterfalls and birds and winds sing. I’ll interpret the rocks, learn the language of flood, storm, and the avalanche. I’ll acquaint myself with the glaciers and wild gardens, and get as near the heart of the world as I can.”

Mikki says she thinks of Joe when she’s out in the mountains, when she feels the wind and sees the view. When she feels most alive, that’s when she senses his presence, too. “Being with Joe allowed me to work through this in a way that I never would have been able to before. He changed the way I saw the world,” she says. “Is it not fair that I lost my husband at 35, just when we were starting our life together? Everyone will tell you that’s not fair. But I got to be with the love of my life for four years. And maybe, just maybe, that’s good enough.”