A wise old mountain man once told me, “You start your life off in the mountains with a handful of luck, and hopefully you gain a handful of knowledge before your luck runs out.” That saying couldn’t be more true.

If planning on heading out into the backcountry, consider taking avalanche courses and learn how to measure the risks and conditions. The kicker is that the more you know the risks, the more you realize you don’t know, which hopefully makes you more cautious.

Over the years I have lost many friends in avalanches, most of whom were experienced and/or professional skiers. While it may be easy to Monday-morning-quarterback their decision-making process, it’s important to remember that no one goes into the mountains expecting to die. The following are some of the things that I’ve personally learned over the years which have helped to keep me safe—and hopefully they will help you as well.

On at the car, off at the bar.

Always turn on your beacon before you leave the car in the morning, and don’t turn it off until you’re enjoying après-ski beers in the lodge. All too often people will turn off their beacon while eating lunch, or while making laps inbounds, and then forget to turn it back on when heading out into the side country. Batteries are cheap, and the consequences of forgetting to turn your beacon back on can be fatal. Some companies are now even making backup transmitters to be used in the event that you forget to turn your beacon on.

Always check your partner’s avalanche equipment before heading out.

Double-check that your partner has a shovel, probe and fresh batteries in their beacon.

Avalanche transceivers are sophisticated electronic devices. Don’t put them in your checked luggage when flying, and always replace your beacon after it’s been subject to a significant impact. Steve Christy from Backcountry Access (BCA) also recommends that most people retire their beacon after five years, and that professionals who use one on a regular basis should retire theirs every two years. For the best information on a specific beacon, refer to the manufacturer’s instructions for life of product.

Airbag technology doesn’t make it safer.

Avalanche air bag systems can and do save lives. I have a friend who wouldn’t be with us today if she hadn’t been wearing an airbag. The slide that she was lucky enough to survive claimed three lives. Airbags are a good last-resort defense when things go wrong. They are not 100 percent foolproof, and they do not make dangerous snowpack conditions safer. They’re just one more tool to help weight the odds in your favor.

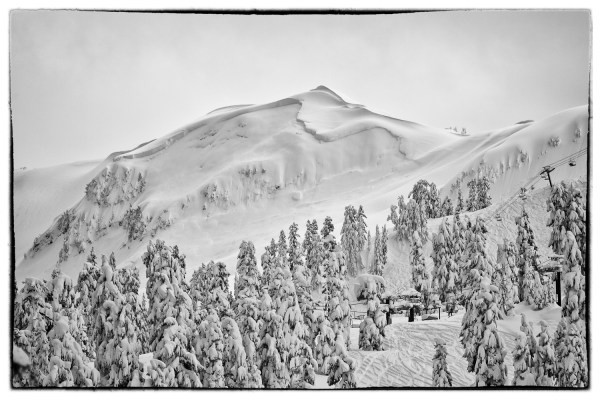

Just because there are tracks doesn’t mean it’s safe.

Don’t be a lemming and blindly follow the herd without doing your own avalanche assessment. The slope in this image was skied countless times and not a single rider stopped to assess the avalanche danger.

Sunny weather doesn’t make it safe.

Countless skiers venture into the side country every time the sun comes out. The snowpack can be the most dangerous on sunny days due to the thermal radiation heating it up. You may not notice it getting warmer, but just a few degrees can make a big difference in the stability.

The mountain doesn’t care if you’re an “expert” or a “pro.”

In fact, the better you are at skiing or snowboarding, the greater the allure of skiing slopes which are more prone to avalanches. It’s also easier to talk yourself into thinking it’s safe the more you know about snow safety. Remember that avalanche safety is never 100 percent. A lot of spatial variability can and does exist in the snowpack, so slopes can and do break in odd and “unusual” ways. This often results in wider and/or deeper slabs than one would expect.

Even small avalanches can be deadly.

Conditions with moderate and considerable avalanche ratings (on the five-level North American Public Avalanche Danger Scale) can be more dangerous than conditions with a high avalanche rating. Most people think the bigger the avalanche the more deadly it is. The truth is that, statistically, small avalanches are more deadly. The majority of avalanche fatalities and accidents involve small slides with relatively shallow crowns.

Large avalanches are typically the result of a weak layer that is days if not weeks in the making. If regularly monitoring snow forecasts and weather patterns, it can be obvious when conditions are right for these large slides. Conversely, when the danger scale is set to moderate or considerable there is a significant degree of uncertainty in the snowpack; thus, it’s much more difficult to predict if it will slide or not. On high avalanche danger days it’s much more obvious.

Take an avalanche-awareness class, but remember, the more you know the more you don’t.

Avalanche classes are a great way to learn the ins and outs of snow safety. It’s also a good idea to take a refresher class every year, even if you have lots of experience with making decisions in avalanche terrain. It’s important to always remember that taking a class is only the start, and it’s up to you to learn to apply that knowledge in a real-life environment. When you’re starting out as a backcountry skier it’s great to spend time practicing your skills with experienced backcountry skiers, especially in your area. This will teach you a lot about making decisions in the local terrain, such as which slopes tend to be more susceptible than others.

Don’t be afraid to speak up.

Humans are not perfect by any means. Do not be afraid to voice your concerns if feeling a little uneasy about the conditions. Just because someone who is a guide or simply has more experience than you says an area is safe, you don’t have to take their word for it. There are many documented cases where an avalanche accident or fatality occurred because someone in the group that had less experience felt uncomfortable questioning the decision of a more experienced group leader. Avalanche professionals, guides and those people that simply have more experience than you are not infallible. They can and do make mistakes.

No one cares how rad your line was.

If you get injured or killed in a slide, your friends, family and kids are not going to care how amazing the line was or if it was the “run of your life.” Avoid making risky decisions in the backcountry based upon your selfish desires to ski a cool-looking line. Don’t go out with a goal of riding a particular line or wanting to achieve a certain objective. Let the mountain talk to you and make conservative, educated judgments based upon the snowpack as it changes during the day.

There is nothing wrong with choosing to stay inbounds.

Backcountry skiing is an amazing experience but some days it’s way more fun to stay inbounds. A wise old mountain man also told me to remember, “There are old skiers, there are bold skiers, but there are no old bold skiers.” There are so many amazing days in the backcountry each year when the snowpack is relatively safe, stable and reliable, so why question it on days that are so uncertain?

If you are interested in winter backcountry classes and events in your area, head over to REI Outdoor School.