Women have been a part of the great outdoors since the beginnings of humanity, even if history books aren’t always filled with their names. For Women’s History Month, we’re taking a look at four women who reshaped the landscape of the great outdoors. Without them, we wouldn’t be where we are today.

Clare Marie Hodges

In 1918, Clare paved the way for future generations when she was hired as the first female ranger for the National Park Service, serving at Yosemite National Park. She first visited Yosemite at 14, riding four days on horseback to reach the valley. She couldn’t stay away, returning to teach at the Yosemite Valley School in 1916. She was still teaching near the end of World War I, when finding men to fill jobs at home was challenging. Clare saw her chance. According to NPS, she approached the park superintendent and said, “Probably, you’ll laugh at me, but I want to be a ranger.” He accepted her, and the rest is history. She spent the summer as a mounted ranger, patrolling the valley and remote areas of Yosemite. She also took gate receipts from Tuolumne Meadows to park headquarters, which involved an overnight ride on horseback.

NPS History Collection (HPC-001917)

Emma “Grandma” Gatewood

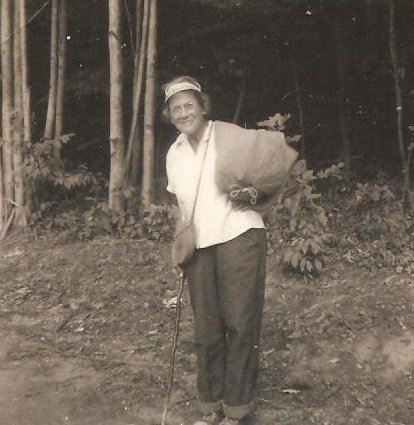

One day in 1955, Grandma Gatewood told her family she was going for a walk. It turns out she was planning on hiking the entire 2,190 miles of the Appalachian Trail alone, to become the first woman to accomplish the feat. She was 67 and hiked the trail in sneakers with an Army blanket, raincoat and plastic shower curtain in a homemade denim bag that hung over one shoulder. She gained national attention during her hike, appearing in Sports Illustrated and on the “Today” show. But finishing once wasn’t enough. She hiked the AT again in 1957 and for a third time, in sections, in 1964, becoming the first person to hike it three times. In 1959, she walked from Independence, Missouri, to Portland, Oregon—2,000 miles in 95 days. She also helped establish the Buckeye Trail in Ohio, leaving a 1,440-mile-long legacy.

By Stratness (Wikimedia Commons)

Margaret “Mardy” Murie

Known as the grandmother of the conservation movement, Mardy looms large in our collective memory. She was born in 1902 and raised in the Alaskan wilderness. When she started college (later becoming the first woman to graduate from the University of Alaska), she met a scientist named Olaus Murie. They married on the banks of the Yukon River, solidifying their love of the wilderness. After they wed, they studied caribou on a 500-mile expedition by steamship and dogsled. The couple then began conservation work, writing articles, giving lectures and fighting for legislation to protect wilderness areas. In 1956, they studied wildlife in the Upper Sheenjek Valley, Alaska, and used their research to convince President Eisenhower to create the country’s only conserved place that encompasses an entire Arctic ecosystem: the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Olaus died in 1963 and Mardy took over his conservation work. For decades, the government and conservation groups relied on her. But her biggest moment came in 1975 when she joined a task force that traveled to Alaska to find land to be protected from economic development. She testified before Congress, which pushed President Carter to sign the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act into law—preserving 157,000,000 acres of land and tripling the size of the wilderness system at the time. Although she died in 2003, her work continues on in the Murie Center nonprofit.

Photo of Olaus and Mardy. English, Edith; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – NCTC Archives/Museum

Dr. Carolyn Finney

Dr. Carolyn Finney, our modern-day historical figure, is changing minds, educating the country and serving on nonprofit boards. Dr. Finney grew up on a 12-acre estate outside of New York City where her parents were caretakers of the property and the first people who taught her about conservation. In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, along with pursuing an acting career, she spent the better part of five years backpacking around the world and living in Nepal. She next went back to school after a 15-year break to get her master’s in international development and then her doctorate in geography. She went on to teach about how people interact with the environment at the University of California, Berkeley before becoming an assistant professor of geography at the University of Kentucky. She served on the National Park System Advisory Board and is now part of The Next 100 Coalition. The Next 100 Coalition gathers the power of leaders in civil rights, environmental justice, conservation and communities to advocate for inclusive public lands. She also wrote the book, Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans and the Great Outdoors, which published in 2014.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Carolyn Finney.