Kate Siber remembers clearly the magic of her first national park visit: She was 10. And the cliffs of Grand Canyon National Park and the Havasupai Tribe’s adjacent land made a huge impact. “Coming from an urban upbringing, I was completely blown away by the cliffs, the red hue of the rock, the crazy waterfalls and the clear blue skies,” she says. “It was as if a curtain pulled back and all of a sudden I realized that the planet is capable of unimaginable wonders.” And it’s that same sense of awe—and an eye for magnificent detail—that she brings to young readers in her new book, National Parks of the U.S.A.

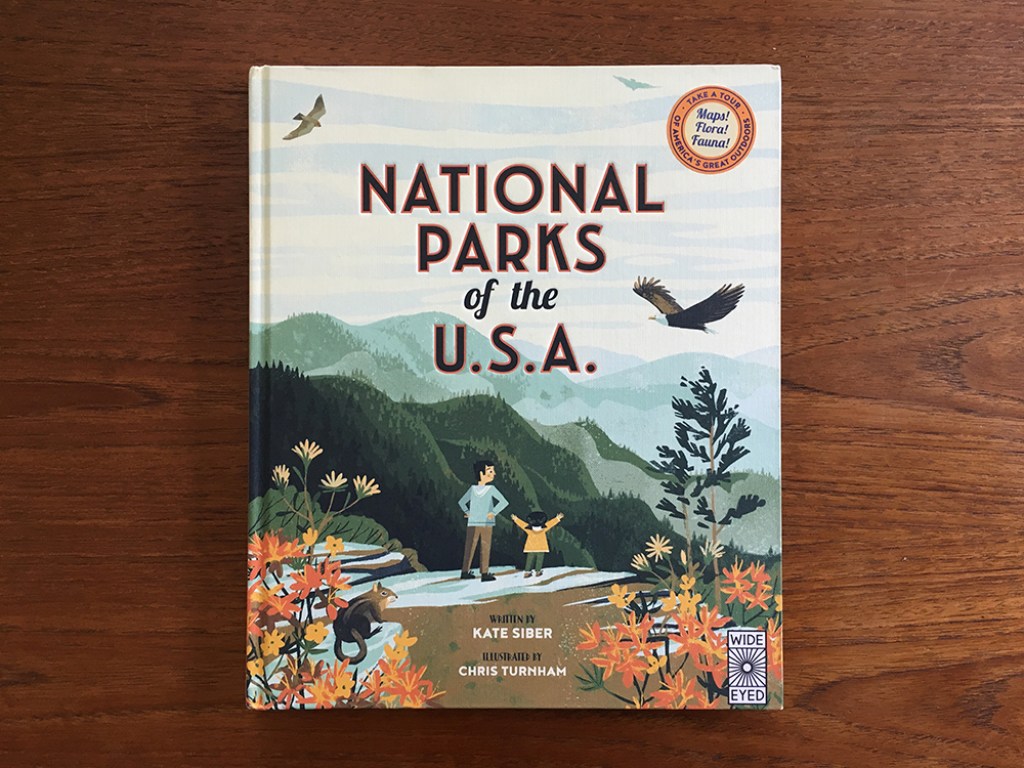

Kate Siber’s new children’s book is a treasure trove of information about our national parks—from Death Valley to the Virgin Islands. Photo courtesy of Chris Turnham.

Drawing from a lifetime of adventure, Kate partnered with illustrator Chris Turnham to create a 100-page volume packed full of facts and characters from locations as diverse as Death Valley and the Virgin Islands. Kate spoke with dozens of park rangers about what kids love about their parks and dove into studies, papers and field guides to find the most interesting tidbits for the book. Like, for example, the fact that Yellowstone’s hot springs aren’t brightly colored because of the water—it’s actually the bacteria in the water, which can withstand incredibly hot, acidic conditions. Or, the fact that a furry creature called a fisher—which can be found in Yosemite and other national parks—is one of the few species that can kill a porcupine!

We asked Kate about the most interesting things she learned in her research—and what her most important conclusions about our national parks were. Here’s what she had to say:

Sometimes the most interesting animals aren’t the big, famous ones like the bison, bear and wolf. “I was most captivated by some of the small critters that do remarkable things, like the prairie dogs in Badlands National Park. They are a keystone species in the grasslands and provide habitat and food for all sorts of other animals, like the burrowing owl, which finds shelter in prairie dog tunnels. Or the ringtail. I like to think of ringtails as a cross between a cat and a raccoon—that’s a highly unscientific description! They live in the Southwest and are incredibly cute and acrobatic—they can do cartwheels!”

A page detailing fun facts about the plant and animal life of Yellowstone National Park. Photo courtesy of Chris Turnham.

There are still places left that feel “out there” and untouched. “I once did a backpacking trip in Alaska’s Wrangell-St. Elias National Park & Preserve in which we got dropped off in the middle of nowhere and had to hike our way out, fording rivers, crossing glaciers and passes, dodging bears and bushwhacking through endless willows. It made a huge impact on me being in wilderness like that—that park is the size of Yellowstone, Yosemite and Switzerland combined. We not only didn’t see people but didn’t even see any signs of people—not a footprint, not even a contrail. The vastness completely blew my mind.”

There was a time when national parks were treated more like amusement parks. “For a while, the parks were in some ways seen as pleasure grounds for vacationers—I think there was a skating rink in Yosemite, if I remember right, and most summer evenings embers from a bonfire would be tossed off the cliffs at Glacier Point to create an illuminated waterfall for the visitors’ amusement. I think they stopped that practice as late as the 1960s. Now, of course, the park service is less concerned with entertaining people and more concerned with educating and informing people of the natural resources that are available to us. So times and mores and outlooks change, and that’s reflected in our public institutions. It makes me wonder what the parks will look like 50 or 100 years from now.”

Detail from the pages devoted to Olympic National Park: “Zip up your raincoat! You’re in a deep, dark, silent rain forest that smells of cedar.” Photo courtesy of Chris Turnham.

In fact, national parks were even protected by the military at one time. “When Yellowstone was formed in 1872, Congress didn’t appropriate any money for a superintendent or rangers or infrastructure of any kind. For many years, people came to Yellowstone and poached the animals and fished out of the streams and even pried off bits of geyser rock to take home as souvenirs. Eventually, the military was called in to protect the parks. And, of course, eventually, in 1916, the National Park Service was formed. This early story underscores the need for parks not only to be designated but actively stewarded. Parks need champions if they are going to survive well into the future.”

Our national parks face many threats to their existence as we know it. “There are a lot [of threats], from chronic underfunding and a huge backlog of maintenance to climate change, unsustainable tourism, and development in and near parks that affect wildlife corridors and viewsheds. … There will probably always be threats to these wild places, which means we have to actively stand up for them. It also means that it’s really important to enjoy them. Our love for these remarkable places is what fuels us to carry on protecting them. We must always remember to connect—they remind us of our humanity in a day and age when it’s so easy to forget.”

The author traveled to national parks throughout the United States and interviewed dozens of park rangers while working on the book. Photo courtesy of Kate Siber.

A national park is a great place for a first venture into nature—which is super important, it turns out. “The indoors-ification of our culture—especially for our youth—really concerns me. Through this book, I wanted to get kids excited about nature in national parks and well beyond. I mean, the natural world is ridiculously entertaining when you actually take a moment to look. Some of the wild stuff animals and plants do to survive … you can’t make it up. I was constantly telling my friends weird factoids I discovered. They were probably rolling their eyes. … The national parks are a wonderful gateway for people. They’re an opportunity to rediscover nature everywhere. It obviously isn’t limited to these tidy areas within boundaries. It’s in your backyard. It’s overhead. It’s growing up through the cracks in the sidewalk.”

Kate’s tips for taking kids to national parks?

- Try the Junior Rangers Program! “Kids generally love it. And they get a badge at the end—fun!”

- If you’re going to multiple parks, opt for an annual pass—it will pay off.

- Where it’s possible, aim to get off the beaten path. It might take applying for a permit and doing a bit more advance planning, but it will be worth it. “The vast, vast majority of visitors don’t stray very far from their cars, so when you get out into the backcountry, you can access beautiful experiences of solitude and wilderness.”