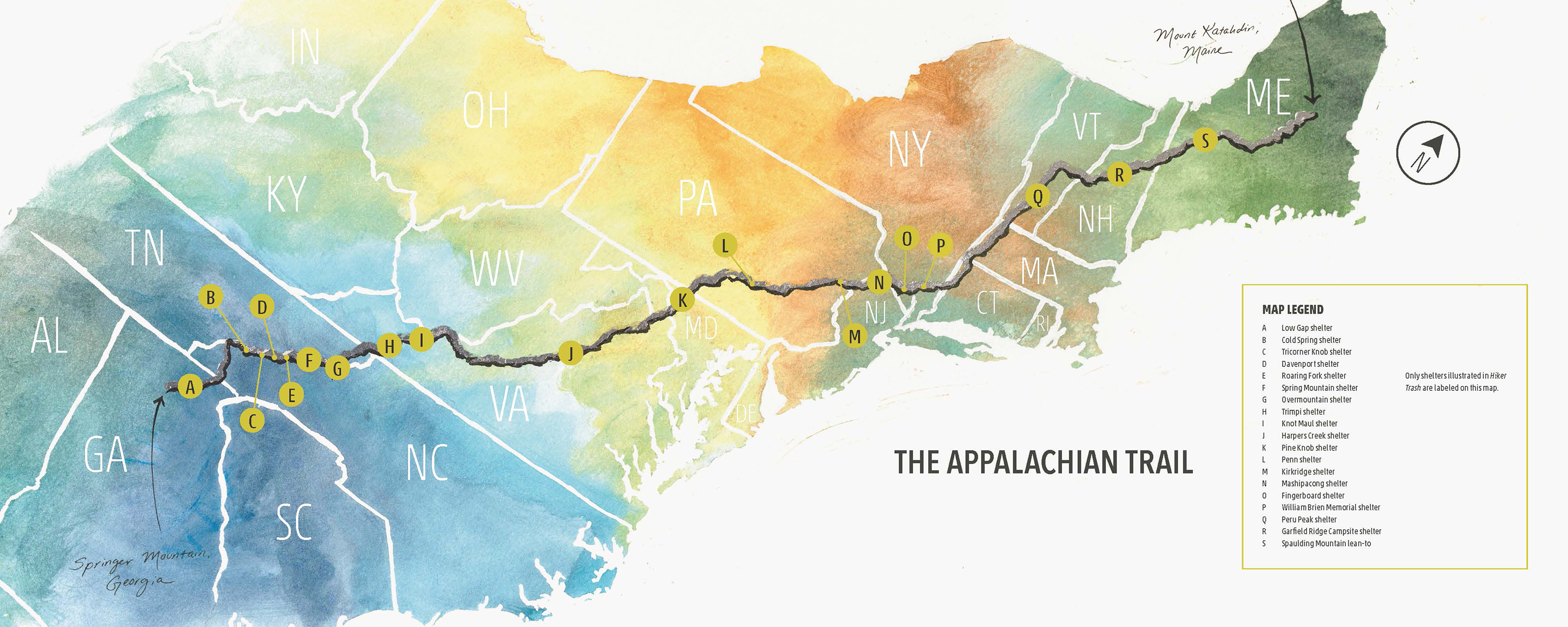

It takes just under six months for most backpackers to complete the world’s longest hiking-only footpath, but you can get a glimpse of the highs and lows of a thru-hiker’s journey without leaving home this fall with the new book, Hiker Trash: Notes, Sketches, and Other Detritus from the Appalachian Trail.

Author and artist Sarah Kaizar joined the ranks of Appalachian Trail (AT) thru-hikers in March 2015, beginning her journey in Georgia after her father passed away, and completing her hike in September. Though Kaizar thought about recording her experience while she was on the trail, it wasn’t until 2016 that she finally put pen to paper.

The resulting collage of backpacking culture pairs her words and illustrations with color photos shot by professional photographer Nicholas Reichard. The book documents life on the AT, paying particular attention to its 250 shelters and the community that routinely finds respite beneath their roofs.

Here, Kaizar speaks about what inspired her to tackle the 2,190-mike trail and how the project came to fruition.

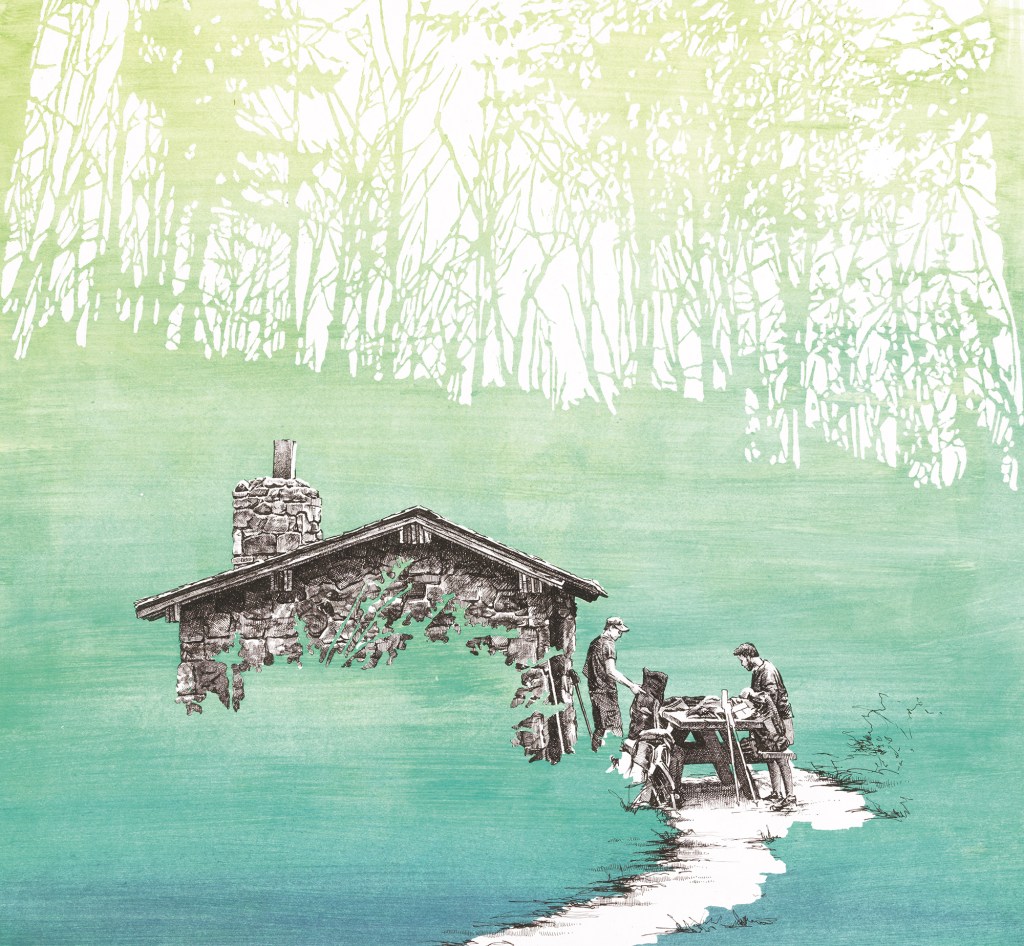

Spring Mountain shelter, Tennessee. Illustration: Sarah Kaizar.

On when the idea to hike the trail took hold. “I had backpacked a lot of sections of the Pennsylvania part of the AT during high school and college. [That section is] about halfway through, and there are all these trail markers that say ‘this many miles to Maine and Georgia.’ They seemed like an impossible distance. … [An AT hike] was always in the back of my mind, a backburner dream for a long time. Then my dad passed away, and after he passed, it put some new urgency into things. It kicked it into a higher gear. It fell into the category of ‘life is too short.’”

Flick on Mount Katahdin. Photo Credit: Nicholas Reichard.

On what she was searching for. “I was definitely aiming for peace and clarity. When I was out there, I was alternatively processing and avoiding processing the grief I was in. Meeting other people who were going through their own challenges made [me] feel less alone. That was eye-opening and comforting. I was expecting a lot of solitude, which you certainly find. But I wasn’t expecting to make this kind of community. I’ve made friends I’m certain I’ll have for life.”

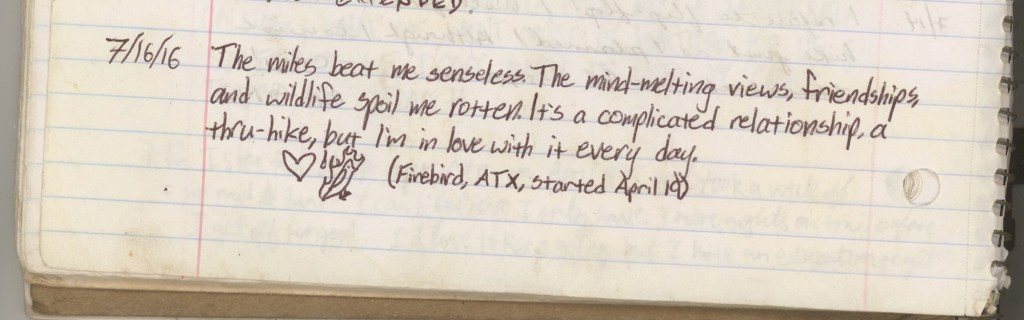

Logbooks are found in many shelters throughout the trail. This is one thru-hiker’s entry. Kaizar used these handwritten notes to illustrate the diverse experiences of the community.

On the camaraderie she found on the trail. “It’s a kind of funny experience, because you’re testing yourself physically, mentally, emotionally. You’re operating in a very vulnerable place, and so is everyone around you. I think it’s easier to make a connection when everyone is in the same state of mind and you’re all moving toward a common goal.”

On what she brought home with her. “[The AT] messed me up in the best way possible. I feel like it was kind of tough to come back to real life afterwards. It took a little bit of transition. I loved the simplicity of backpacking, where you’re carrying everything you have and need. And you’re moving, sleeping, eating. When you’re actually living it day to day, that simplicity is profound. I keep trying to simplify at home. … Actually accomplishing it is pretty empowering. I came home, and what came with me was, ‘What can I do now?’ If I could do that, I can do all sorts of things I didn’t think I could do.”

Fellow thru-hikers Pony Puncher and Food Truck rest at Gentian Pond shelter. Photo Credit: Nicholas Reichard.

On the importance of AT shelters. “When I was on trail, I packed a sketchbook with me, which became waterlogged in the first weeks and had to go. But I was photographing all the [AT] shelters obsessively. I documented almost all 250 shelters. They’re built and maintained by volunteers. They are all a little different. They’re as utilitarian as it can get. So when I sat down and put pen to paper, I started with the shelters first, because I loved them. But in the drawings, it was really the hikers and the community that started making them feel alive.”

Trimpi shelter, Virginia. Illustration: Sarah Kaizar.

On creating Hiker Trash. “Making the book was surprisingly emotionally difficult. I wanted to do some kind of work [after completing the hike], because making artwork is how I process things. But I was also going through a hard time when I was out there. Making the drawings [brought] that back up. I would go through the photos and think ‘I remember that day.’ It was cathartic, but difficult.

“When I started writing, I made trips to the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club in Virginia, the only trail organization that keeps an archive of logbooks. I poured through the pages of the logbooks, and in those pages, the hikers got really reflective, because they were near the halfway point. The emotional, reflective entries resonated with me. Going through those books, I felt the community of the trail right there all over again.”

Two thru-hikers, Knock and Honeybuns, celebrating the end of a half-year adventure atop Mount Katahdin. Photo Credit: Nocholas Reichard.

On who she created the book for. “I’m hoping the book is kind of waving [a] flag: There’s this great group of people out here, and there’s this great experience. It’s fully open to anyone who wants to come out to it. I’m hoping [that] a lot of the voices of the trail call out to people through this book.”

Editor’s note: Images were used with permission from Hiker Trash: Notes, Sketches, and Other Detritus from the Appalachian Trail (Skipstone/Mountaineers Books, September 2019) by Sarah Kaizar, with photos by Nicholas Reichard and logbook entries courtesy of the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club.

Read more:

- 21 Appalachian Trail Statistics That Will Surprise, Entertain and Inform You

- How to Pack for an Appalachian Trail Thru-Hike

- The 7 Hardest Day Hikes on the Appalachian Trail

- Paul’s Boots

- How Much Does it Cost to Thru-Hike the Appalachian Trail?

- The Appalachian Trail vs. Pacific Crest Trail: Which Hike Is Right for You?